![]()

1

What’s in a Face?

Jonathan Phang

I found growing up in London during the 1970s very confusing. Wherever I went, I never seemed to fit in; to me, my facial features looked weird, and as a result, I felt like I had nothing in common with anyone. Unsurprisingly, I became introverted, and often felt like a square peg trying to squeeze into a round hole. During puberty, people were either intrigued by my indefinable looks or threatened by them. Due to my height, large frame and wavy hair, people presumed that my heritage was Samoan or Tongan, and expected me to be good at rugby. Sadly, I wasn’t, and I became the class booby prize on the playing field, as well as off it.

Although my home life was privileged and loving, I felt displaced there, as I did at school. My family expressed themselves in a completely different way to everyone else. We were boisterous, ate Caribbean food, and listened to reggae and calypso instead of rock and pop. My father looked Chinese, but sounded West Indian (unless he was engaging with an English person, at which point he’d affect an accent that was more English than the English). I yearned to blend in and feel normal; instead, I felt awkward, isolated and embarrassed about who I was, but despite this, I never felt ashamed of my parents.

I was aware that my weekends were different from those of my classmates, so on Monday, I would play down what I had done. Most people went to the pictures on Saturday morning, followed by football with their dad, or perhaps a sleepover with friends. On Sunday, they might have a roast dinner with their grandparents, followed by a country walk, board games, telly or something else that they might enjoy. In other words, life centred around them. In contrast, we spent our weekends indulging my father. Generally, this meant entertaining several of his friends, who would spend Saturday afternoons in front of the television, studying form and gambling on the horses, while eating us out of house and home. Meanwhile, my mother and the female visitors would spend all day cooking and serving the men. I sought refuge in the kitchen and gratefully learned how to cook curry and roti, pepperpot, garlic pork, chow mein, pine tarts and patties, along with various other Guyanese and Chinese delicacies. For hours on end, I listened with great interest to their gossip and sentimental anecdotes from ‘home’, and I wondered, had their journey to the motherland met their expectations, or did they still dream of more?

Our Sundays were usually spent in Chinatown, wearing our best clothes and devouring our body weight in dim sum. We would then get bored listening to my father holding court with half of the West Indian Social Club and other Chinese Caribbean immigrants, who spent their day off liming (doing nothing in particular) in Gerrard Street. I kept out of my father’s way. My mother instilled in us that children should be seen and not heard, and that as Lord master and provider, our father needed rest and should be allowed to enjoy his day off with his friends without interruption.

In my mind’s eye, the ‘home’ that everyone kept going on about was a tropical paradise, bursting with grand palm-lined boulevards, flanked by elegant whitewashed wooden houses, embellished with filigree fretwork, shaded by Demerara shutters and flaming flamboyant trees. This utopic world of my naive imagination knew nothing of what it meant to be born in a country colonised by Europeans, where Africans had been enslaved and where Portuguese, Chinese and Indians had been indentured labourers. No one, including my family and teachers, could shed any light on the history of my cultural heritage, Guyana, or any other of Britain’s’ colonies for that matter. I had no perception of what being British was supposed to mean to someone like me, and I certainly couldn’t understand why my family held Queen and Country in such high regard. To this day, few people know about the British Empire’s system of indentured servitude that resulted in Guyana’s Indian, Chinese and Portuguese population and which is part of my own family history.

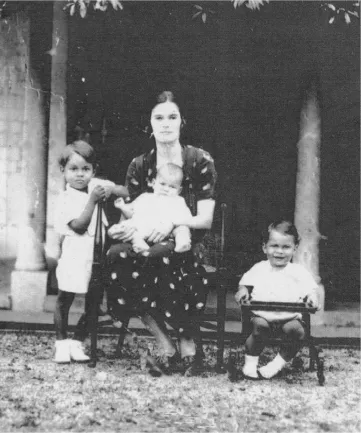

My parents’ love story was legendary in Georgetown and is fondly remembered by those involved with their courtship. They had met by chance, one afternoon in 1950, while my mother was walking home from St Rose’s convent school with her classmates. From all accounts, it was love at first sight; my mother was what would have then been termed a ‘mulatto’, and few could pinpoint where her ‘exotic’ looks originated (see Figure 1.1). She could have been from anywhere between Latin America and the Middle East. She had razor-sharp cheekbones, dark, deep-set, almond-shaped eyes with perfectly arched eyebrows, and an engaging dimple on her left cheek. She was statuesque and beautiful; this gave her an air of confidence beyond her years.

Figure 1.1 My mother Maureen. (Photo courtesy of Jonathan Phang)

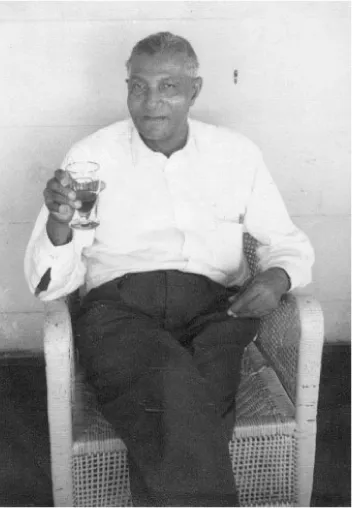

It took a whole year before the love-struck pair went out on their first date. My mother was only 15 when they met; my father was eight years her senior. My father was mindful and wary of their age difference; he told her that he would not court her until she had graduated from high school. Despite her frustration, my mother was confident that he was the man for her. She proudly told all her school friends that she would marry Roy Phang and have plenty of chubby Chinese babies. She waited patiently for the year to pass. In the mean time, she befriended Roy’s cousin Margery and engaged more with the Chinese community, ensuring that he was aware of her every move, and making it impossible for him to get her out of his mind. My honourable father remained true to his word and stayed away from her until she completed her education. Occasionally, he’d send her affectionate tokens via cousin Margery to keep her interested. He sensed that their relationship was never going to be easy as he knew there was the matter of race, and Maureen’s tyrannical father, Cyril (see Figure 1.2).

The Chinese community was one of the smallest minority communities in Guyana, and they tended to keep themselves to themselves; they rarely married ‘out’, especially to a ‘creole’.

My grandfather, Cyril, was the eldest of seven children born to John and Mary Elma. John was the favourite illegitimate child of a Dutch Jewish plantation owner named Bollers. Bollers was originally from Paramaribo and had several Amerindian and ‘mulatto’ mistresses. He was unlikely to have been aware of the number of children that he had fathered. However, as John’s mother was one of his preferred paramours, he chose to recognise him, and though he eventually grew tired of John’s mother, he spotted something special in the handsome, young John and removed him from the cane fields (and his mother) to have him privately educated. John was a charismatic and naturally intelligent child who thrived at school and took exams in his stride. He graduated from Edinburgh University in the 1890s and returned to the West Indies with a First Class Honours degree and a white Scottish bride, whose looks were at best considered ‘handsome’. At that time, Georgetown, with its pretty tree-lined streets and picturesque canals, was known as the Garden City of the Caribbean, and Guyana itself was one of the most lucrative jewels in Britain’s colonial crown, with fertile plains, mineral mines and dense rain forests. John’s rise to wealth and power was rapid. Among other things, he became Chairman of the country’s largest drugstore, Secretary of the British Guiana & Trinidad Mutual Fire Insurance Company and a member of the Georgetown Town Council.

Figure 1.2 Cyril Bollers, my maternal grandfather. (Photo courtesy of Jonathan Phang)

Mary Elma enjoyed the trappings that came with being an affluent white mistress in nineteenth-century Georgetown society. She grabbed every advantage without conscience or empathy and ruled her household with an iron fist. She was the driving force behind her husband’s success, and for a time they were Georgetown’s glittering couple, but as John’s star rose, his interest in his wife waned. She had convinced herself that bearing children would solve their problems. John did not know the exact details of his heritage, so he concocted a convincing tale that satisfied even the most curious minds, including that of Mary Elma. However, when her first child was born (my grandfather Cyril), it was evident from the baby’s physical appearance that there was far more to John’s story than he had revealed, and she began to question his motives for marrying her.

Her misgivings were in vain; she had made her bed, and she had no choice other than to lie in it. Cyril’s birth ignited a vicious streak in Mary Elma’s character, and there were times when she could barely stand to look at him. As her other six children were born, each fairer than the last, her scorn for Cyril grew. He was not allowed to play with his siblings in public, and while the family entertained, his mother often hid Cyril in the attic, refusing to mention him. Cyril became withdrawn and developed a nervous disposition. Mary Elma’s decision to send him away to school in England as soon as he was old enough exacerbated his idiosyncrasies and affected his mental and physical well-being for the rest of his life.

Cyril returned to Georgetown at the turn of the twentieth century, broken by the brutality of British public school. He was the only pupil of colour, and he suffered daily bullying and humiliation from students and teachers alike. Cyril was naturally bright and had aspirations to become a doctor; however, he contracted osteomyelitis at school and endured several operations that interrupted his studies. With his ambitions thwarted, Cyril felt that his only hope of being accepted into society and pleasing his parents would be to marry a white girl and start a family.

My grandmother Maude was a beautiful ‘local white’ from Barbados (see Figure 1.3). She was descended from indentured servants and labourers from Scotland and Madeira, who most likely met and worked on the same plantation. After emancipation, formerly enslaved Blacks could train in all key trades, so there was no longer a need for cheap white labour. The local whites were unwilling to work alongside the freed Blacks (who were less expensive to hire). Instead, they chose to emigrate to other British colonies to find better opportunities.

Figure 1.3 My maternal grandmother Maude. Her eldest son, John, is pictured standing. (Photo courtesy of Jonathan Phang)

By the time Maude arrived in Georgetown, she had blossomed into a sultry-looking young woman. She had waist-length auburn hair, a curvy figure and sparkling hazel-coloured eyes. Her pale complexion had deliberately been kept out of the sun and belied her Portuguese heritage. Maude’s people were thrilled for their daughter to be marrying into such a distinguished family, but Mary Elma was incandescent with rage, and she was, as always, less than impressed with Cyril. She considered Maude to be a ‘redleg’, which in her opinion was the lowest of the low, and made it clear that Maude would never be welcome into her family.

‘She is a good woman, and she has such a beautiful face!’ Cyril protested.

‘But it’s what’s in her face that matters. With that “Putagee” widow’s peak and red skin, her face says it all! She’s not even good enough to be one of my maids! Never bring that shameful low-class white into my house. Ever!’

Cyril and Maude’s wedding was a sombre event that my maternal great-grandparents did not attend, and Maude was never welcomed into her in-laws’ home. It appeared that there was nothing Cyril could do to earn approval from his parents. His father had pretty much written him off, but he did pull strings and find him a job as a floor manager at G. Bettencourt & Co., a lowly position for someone from such a distinguished and ambitious family, but respectable nonetheless.

I believe that Cyril truly loved Maude. As a child, he told me many times the story of how he fell in love with her beautiful face at first sight, and how her waist-length wavy hair made her look like an angel. By the time Maude was pregnant, within a year of getting married, her life was no better than that of one of Mary Elma’s maids. Cyril had inherited his mother’s vicious streak, and unleashed all of his frustrations on Maude. With each year, Cyril grew more angry and bitter. His eldest son John physically resembled him the most, but unlike Cyril, he was a spirited and strong-willed boy who hated how Cyril treated his mother and younger siblings, and he wasn’t afraid to let him know it. Cyril was brutal when crossed by John, and subjected him to regular beatings. Maude couldn’t bear to witness such violence, and she feared for her son’s life. As a result, John was sent to live with his spinster aunts, and never returned home. It took a decade and a change of country before John got to know my mother again. Maude continued to live her life under duress, and inevitably, it wasn’t long before another of her children experienced Cyril’s wrath. Despite his misdemeanours, Maude remained empathetic and loyal to Cyril. She compensated for his abusive behaviour as best she could by being a devoted mother and spoiling her beloved offspring with an understanding ear and a broad repertoire of delicious homecooked food. In contrast, my father’s upbringing was comparatively idyllic, although his background was similarly lurid and convoluted.

It was in 1853, when the British turned to China for the additional recruitment of indentured labourers, that the first batch of Chinese male ‘cane reapers’ landed in Georgetown. Among them was my great-great-grandfather Li. Li was a Hakka Chinese fleeing from the T’ai P’ing Rebellion. In an attempt to hide his true identity from the authorities and avoid conviction, he cut off his pigtail, made his way to Canton, offered himself for indentured labour, and boarded a boat bound for British Guiana.

During the arduous three-month voyage, Li developed a close friendship with a man of Indian descent from the Middle Kingdom. They shared a similar background, and both came from societies which regarded women as inferio...