![]()

Chapter One

Revisiting Our Roots

When the roots are deep, there’s no reason to fear the wind.

Chinese proverb

Persons of African descent arrived in present-day Oklahoma in three principal waves: (1) with Spanish explorers in the sixteenth century; (2) with the “Five Civilized Tribes” during their forced migration from the Southeastern United States during the “Trail of Tears” era of the 1830s and 1840s; and (3) in the post-Reconstruction Diaspora from the Southeastern United States, principally in the 1880s and 1890s. It is the latter two waves that gained traction.

The African American journey with their Native American kin has been largely ignored.

“Go West, young man, and grow up with the country” is advice widely credited to Horace Greeley (1811 -1872), a nineteenth century politician and founder of the New-York Tribune. This admonition, consistent with the Manifest Destiny philosophy of the day, encouraged settlement of America’s western lands, irrespective of the “collateral damage” to the indigenous people already there.45

For the southeastern United States-based Five Civilized Tribes (Cherokee, Muscogee (Creek), Chickasaw, Choctaw, and Seminole), “Go West” became not an admonition, but a command. The federal government forcibly removed these tribes to Indian Territory in the West (the eastern half of modern-day Oklahoma) in the 1830s and 1840s.46

The Five Civilized Tribes, all of whom practiced chattel slavery, participated in the Civil War, with combatants and supporters on both sides, but with all tribes officially aligning with the Confederacy. That wartime alignment would have significant consequences.47

The conclusion of the Civil War and the beginning of African American liberation it wrought seemed ripe with opportunities to stake claims to land, and thus further erode the racial caste system that limited life prospects for African Americans. Progress loomed on the horizon.

At a January 1865 meeting with Union General William Tecumseh Sherman and Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton, a black Baptist minister named Garrison Frazier, himself formerly enslaved, responded to the age-old question, “What do the Negroes want?” Reverend Frazier noted: “The way we can best take care of ourselves is to have land, and turn it and till it by our own labor . . . . and we can soon maintain ourselves and have something to spare . . . We want to be placed on land until we are able to buy it and make it our own.” Someone asked the Reverend whether the newly-freed people preferred to live among whites or in relative isolation. He opined: “I would prefer to live by ourselves, for there is a prejudice against us in the South that will take years to get over . . . .” Four days later, having sought and gained the approval of President Lincoln, General Sherman issued Special Field Order No. 15.48

The common refrain, “forty acres and a mule” traces back to General Sherman’s Order. The Order itself calls for up to forty acres of tillable ground per family in specified parts of the South. Field Order No. 15 makes no mention of mules.49 However, General Sherman later decreed that the Army could lend the unseasoned settlers mules—beasts of burden—to assist them on their newly-acquired land.50

This bold gesture of reparation swelled the hopes on many formerly enslaved African Americans. They believed and were told by various political figures that they had a right to own the land they had long worked while enslaved. They were eager to control their own property, and their own destiny.

Theirs would be a dream deferred. President Andrew Johnson, Lincoln’s South-sympathizing successor, countermanded Order No. 15 in the fall of 1865, ceding the lands back to the southern planters who had waged war on the United States.51

Still, freed people widely expected to legally claim 40 acres of land and a mule after the end of the Civil War, long after the reversal of proclamations such as Field Order No. 15 and the Freedmen’s Bureau Act, which also offered various assistance to these now-freed persons.

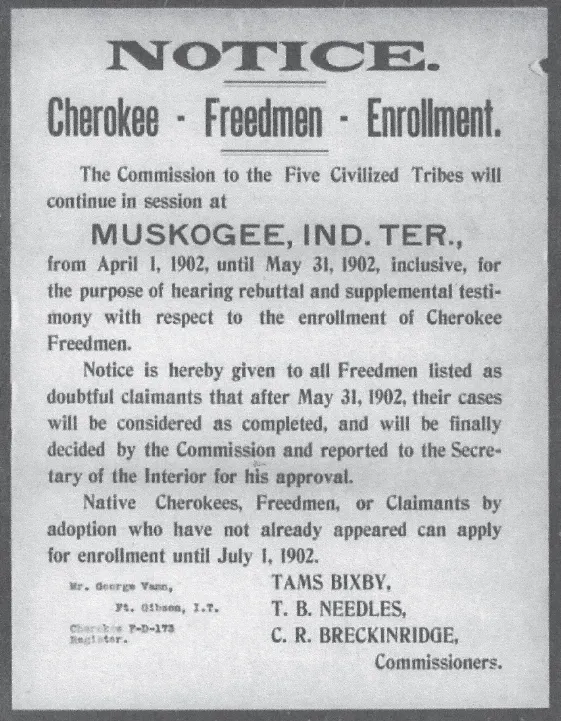

Example of a Cherokee Freedman notice of Dawes Commission hearing from 1902.54

For the Freedmen in Indian Territory (part of present-day Oklahoma), the persons of African ancestry living among the Five Civilized Tribes, access to land became a real and enduring reality. The Freedmen received land allotments pursuant to their tribal relationships, based upon the Treaties of 1866 negotiated between the Five Civilized Tribes and the federal government after the Civil War, and pursuant to the Dawes Commission allotment process that broke up communal tribal lands.52 By act of Congress on March 3, 1893, the federal government charged the Dawes Commission, named after its chairman, Senator Henry Dawes of Massachusetts, with negotiating agreements with the Choctaw, Muscogee (Creek), Chickasaw, Seminole, and Cherokee Nations.53

In addition to this forced migration with Native Americans, the post-Reconstruction Diaspora brought African Americans to Oklahoma. Prominently in Kansas, then principally in Oklahoma, all-black towns founded by black visionaries and risk-takers like E.P. McCabe mushroomed in the post-Reconstruction era. Weary Southern migrants formed their own frontier communities, largely self-sustaining and self-governing. These rural, all-black towns offered hope—hope of a respite from second-class citizenship; hope of political self-determination; and hope of full participation through land ownership in the American economic dream.

African American booster E.P. McCabe and others touted Oklahoma, then divided into Indian Territory and Oklahoma Territory, as a virtual “promised land” for African Americans. McCabe dreamed of an all-black state carved out of Oklahoma Territory. He and his equally ambitious late 1800s-contemporaries sought to wean African Americans from the breast of that special form of Southern hospitality on which they had been nursed—racism.

Oklahoma attracted hordes of weary Southerners fleeing the oppression of the Jim Crow South. Though McCabe’s “black state” dream never materialized, Oklahoma boasts more than fifty all-black towns throughout its history—more than any other state. These are, in part, McCabe’s legacy.

The promise of Oklahoma faded significantly when it became a state in 1907. The new Oklahoma Legislature passed as its first measure Senate Bill Number 1. That law firmly ensconced segregation as the law of the land in Oklahoma. Jim Crow reigned.55

Despite an auspicious beginning, the all-black town movement crested between 1890 and 1910, a time when American capitalism transitioned from agrarian to urban. This seismic change, coupled with tectonic social, political, and economic shifts, ultimately sealed the fates of these unique, historic black oases. Many perished. Most faded. Only the strong survived. Those that remain serve as monuments to the power of hope, faith, and community and testaments to the indomitable human spirit.56

Early in the twentieth century, the black community in Tulsa—the “Greenwood District”—became a nationally renowned entrepreneurial center. In segregated Tulsa, the Greenwood District resembled an all-black-town-within-a-town.

The bulk of the Greenwood District sits on what were once Cherokee land allotments, with a small portion consisting of Muscogee (Creek) township lands set aside by the federal government. Land represents access to economic, political, and social standing-to the American Dream. For African Americans, particularly in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, land served as the handmaiden of true freedom.

Upon this land, this parcel with Native American roots and ties, this downtown-adjacent acreage, the Greenwood District emerged.

Eli Grayson, a multiracial citizen of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation with ancestors listed as both Creek Freedmen (i.e., descendants of formerly enslaved African-originated people) and Creek by blood (i.e., descendants of people with ethnic Native American ancestry), bemoaned the lack of focus on the role of Creeks of Indian and African descent in creating the relative wealth in Tulsa’s Historic Greenwood District.

Unfortunately, the story [of Tulsa’s Historic Greenwood District] is always told without understanding the circumstances that created this community and its wealth. What drew thousands of black immigrants from other states to the newly-created state of Oklahoma? This migration happened at a time when Jim Crow laws were at their harshest. My hope is that at some point one of the journalists who writes about Black Wall Street will thoughtfully consider this question.

The story of the Greenwood District cannot be told completely without understanding the history of African chattel slavery by the Five Civilized Tribes in Indian Territory and, specifically, in the context of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation. Citizens within these Indian Nations held people of African descent as property, freeing them after the Civil War through treaties in 1866 and making them tribal citizens with all the rights of Indian citizens. The Creek Freedmen land allotments are the foundation on which the wealth of the Greenwood District rests.57 These allotments drew thousands of black seekers, particularly from the Deep South, to the area. These new migrants did business with the Creeks of African descent already present.

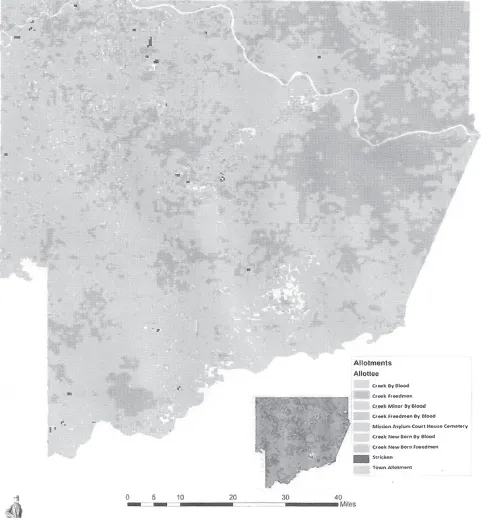

The map below shows the Creek Nation Territory domain. A clear one-third of the Creek Nation allotments, including mineral rights, went to its black citizens.

Allotments of the Creek Nation 1899 thru 1906 According to Classifications of Creek Citizens

It is my hope that journalists and others become more curious about the pre-history of Tulsa’s Historic Greenwood District.58

Buck Colbert Franklin, a prominent attorney in the early Greenwood District and the father of eminent historian Dr. John Hope Franklin, mused about the relationship of Tulsa to her red and black pioneers:

In the beginning, there was no segregation [in Tulsa] or apparently any thought of segregating the races. They lived together and were buried together. This was due, mostly, to the fact that the Indians and freedmen owned most, if not all, of the land. The federal government was in sole control of the titles to these lands, either directly or indirectly, and did not concern itself with the separation of races. In those days, I recall that Negro lawyers maintained their offices in downtown Tulsa and employed a white stenographer. There was at least one Negro barbershop, as well as a real estate office. At Archer and Cincinnati there was a [rooming house] patronized by both races, and on the surface at least, no one thought anything about it.

A few years before statehood [1907], however, there came to Tulsa two very rich Negroes, O.W. Gurley59 and J.B. Stradford,60 who immediately invested large sums in large acreages of real estate ‘across the track.’ Gurley bought some thirty or forty acres and had it surveyed, plotted into blocks, streets, and alleys, and put upon the market to be sold to Negroes only.61 Then adjoining land was purchased by real estate men of other races, plotted and surveyed, streets and alleys laid out, and placed upon the market to be sold to Negroes only; and ever afterward the same process was repeated. In the end, Tulsa became one of the most sharply segregated cities in the country.

* * * *

Following the great holocaust, there was a great letdown in faith, ambition, hope, and trust. The immediate future was blank. Two of the greatest leaders, O.W. Gurley and J.B. Stradford, pulled up stakes and moved away, the former to California and the latter to Illinois.62

Sometime in the early nineteen-teens, legendary African American statesman and educator, Booker T. Washington, reportedly dubbed Greenwood Avenue, the nerve center of the community, “The Negro Wall Street,” later updated to “Black Wall Street,” for its now-famous bustling business climate.63

In 1913, seventeen-year-old Mabel B. Little arrived in the Greenwood District on a Frisco train from the all-black town of Boley, Oklahoma.64 She had only $1.25. Much later in life, she reflected on what she saw upon arrival.

Black businesses flourished. I remember Huff’s Café on Cincinnati and Archer. It was a thriving meeting place in the black community. You could go there almost anytime, and just about everybody who was anybody would be there or be on their way.

There were two popular barbeque spots, Tipton’s and Uncle Steve’s. J.D. Mann had a grocery store. His wife was a music teacher. We had funeral parlors, owned by morticians Sam Jackson and Hardel Ragston.

Down on what went by the name of ‘Deep Greenwood’ was a clique of eateries, a panorama of lively d...