![]()

Chapter 1

The Legend

On one of my many research trips to Oklahoma during the 1980s, I met a black man near Claremore, who gave me information on Cherokee Bill and his relationship to the black community in eastern Oklahoma. The gentleman told me as a child growing up in the black community, a popular refrain was commonly heard in the early 20th century by blacks. It went like this, “If I grow up and don’t get killed, I want to grow up and be another nigger like Cherokee Bill.”

Most of what originally was known about Cherokee Bill came from the book, Hell on the Border: He Hanged Eighty-Eight Men, published in 1898. This book was a 714 page book on Judge Isaac C. Parker and the federal court at Fort Smith, Arkansas, which had jurisdiction over the Indian Territory. At this time in American history, this was the largest federal court in the United States with more than 75,000 square miles within its jurisdiction. Much of what was written about Bill was incorrect, except for the courtroom proceedings, but it did lay the framework for the legend of this outlaw.

Hell on the Border also went into great detail with the significance of the number 13 with Cherokee Bill’s life. First, it was thought that he had killed thirteen men during his days on the outlaw path; the reward for the capture of Cherokee Bill was $1300; his first sentence to die was pronounced on April 13; in an attempted jail break, Cherokee Bill killed a jail guard on July 26, or twice thirteen; during that fight he fired thirteen shots; when Cherokee Bill was convicted, Judge Isaac C. Parker took thirteen minutes in giving the charge to the jury; the actual hours in arriving at a verdict by the jury was thirteen minutes; the jury and deputy during his trial, who ate and slept together made a company of thirteen; and there were thirteen witnesses for the prosecution during Cherokee Bill’s trial.

Although Cherokee Bill was a citizen of the Cherokee Nation in the Indian Territory and is buried in the National Cherokee Cemetery in Fort Gibson, Oklahoma, there hasn’t been much acknowledgment of him being a member of the Cherokee Nation. On my visits to the Cherokee National Museum in Tahlequah, Oklahoma, I have not seen him mentioned with other legendary Cherokee outlaws such as Ned Christy or Zeke Procter, both seen as Cherokee patriots today or the Cherokee bank robber, Henry Starr, who was released from prison due to his friendship with Cherokee Bill, more on that later.

The famous Cherokee writer, author and Cherokee Nation historian, Robert J. Conley, recognized Crawford Goldsby as a Cherokee citizen in his writings. In his book, The Witch of the Goingsnake and Other Stories, he wrote a short fictional story on Cherokee Bill titled “The Name.” Conley also mentioned Cherokee Bill as a Cherokee outlaw in the book Cherokee which was a pictorial/historical overview of the Cherokee people in the United States. Conley also included Cherokee Bill in his A Cherokee Encyclopedia, which was published by the University of New Mexico Press in 2007.

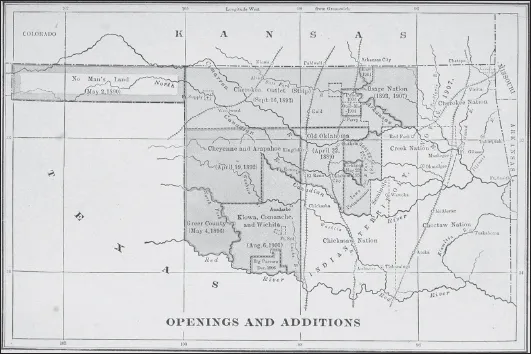

1914 Map of Indian territories and land openings in Oklahoma.

In 1994, the Cherokee husband and wife team of Jack F. and Anna G. Kilpatrick published a book titled, Friends of Thunder, Folktales of the Oklahoma Cherokees that included a section on Cherokee Bill. One of the stories stated “. . . He robbed just about anything, even a train that was traveling at top speed. Cherokee Bill could do it, and if he had to do it alone, he did it. He even disconnected trains while they were in motion, they say, and when he disconnected one, that left one [coach] on the track, and that’s the way he robbed people . . .”

The noted Oklahoma ‘Wild West’ historian Glenn Shirley wrote in his book Toughest of them All:

Take the records of John Wesley Hardin, Bill Longley, Black Jack Ketchum, Sam Bass, or any of the other Western desperadoes, and they can be considered “small potatoes” when compared with Cherokee Bill, the most noted renegade to infest the Oklahoma country in the ‘90s when “there was no Sunday west of St. Louis, no God west of Fort Smith . . .

For more than three years he terrorized this wild country, then known as Indian Territory, and no one cared to attempt to capture him, and at least one town, in the interest of preserving the lives of its citizens, passed an ordinance making it a misdemeanor for anyone to molest him when he was abroad within its limits. Not until a reward of $1,300 was offered for him, dead or alive, did the federal officers begin making plans for his capture . . .

In one respect he was a good deal like the modern bandit. He was “a hand with women.” He had a sweetheart in nearly every section of the country which he traveled, but the one he loved best was Maggie Glass, the cousin of Ike Rogers, a Cherokee Indian, formerly a deputy United States marshal, and intimately acquainted with the killer.

During his criminal career, Cherokee Bill was followed by the New York Times newspaper giving him unprecedented national attention for an African American criminal at that time in United States history. Some writers have said that Cherokee Bill was only known in a regional context, this is not true. During his time he received national attention. He was also followed by other newspapers around the country, much of it having to do with his association with the Bill Cook gang of the Indian Territory. I will list some of the articles from the New York Times later in the text.

![]()

Chapter Two

The Family

Much of what is known today of Cherokee Bill’s origins was originally published in the book Hell on the Border by S. W. Harmon, which was published in 1898. This book focused on the Fort Smith federal court during the Judge Isaac C. Parker reign and the many outlaws and criminals who were captured and executed in that Arkansas federal court and jail. Quite a bit of the book focused on Cherokee Bill because he was the most famous outlaw in the history of the Indian Territory and the Fort Smith federal court. The book stated:

Crawford Goldsby was born at Fort Concho, Texas, February 8, 1876, his father being a soldier in the Tenth Cavalry, United States regular army. He was George Goldsby, now a well-to-do and respected farmer, at Cleveland, Oklahoma, where he is known by the name of Bill Scott. He is of Mexican extraction, mixed with white and Sioux Indian. The maiden name of Crawford Goldsby’s mother was Ellen Beck, she was half Negro, one-fourth Cherokee Indian and one-fourth white. When he was quite young, Crawford Goldsby’s parents separated and until he was seven years old, he lived at Fort Gibson, with his nurse, an old colored aunty, named Amanda Foster . . .

The birth date and place of origins for Cherokee Bill is correct but clarification on the misinformation above was found in a U.S. army pension request that both George Goldsby and Ellen (Beck) Lynch filed for at different times. In the pension request interviews, George stated that many times his name was misspelled as Goosbey or Gouldsby. This was because Goldsby was correctly pronounced, in sound, as Gouldsby, not phonetically as Goldsby as most pronounce it today. Additionally, in the interviews, George stated that he lied about his ethnicity because he was married to a white woman. It was common for African American men and women, if they could, to try to pass for another ethnicity in the late 19th century due to the bias and bigotry against black people in this country. Goldsby was especially vulnerable because he was living with a white woman, which could at that time possibly cause serious injury or his death.

The noted historian and researcher Bennie J. McRae wrote:

. . . In a signed deposition on January 29, 1912, George Goldsby stated that he was born in Perry County, Alabama on February 22, 1843. His father was Thornton Goldsby of Selma, Alabama and his mother was Hester King, a mulatto, who resided on her own place west of Summerfield Road between Selma and Marion, George also stated that he had four brothers and two sisters by the same mother and father, Crawford, Abner, Joseph, Blevens, Marie and Susie.

. . . Ellen was born in the Delaware District of the Cherokee Nation, Crawford’s maternal grandfather was Luge Beck, described as being a Cherokee of the half blood, and grandmother was Tempy Beck. Both had been slaves once owned by Jeffrey Beck, a Cherokee.”

Amanda Foster, an African American, was also interviewed by the Pension Board in Muskogee, Oklahoma, for Ellen Lynch’s request for consideration on February 2, 1912, she was eighty-four years of age at the time. In her interview, Amanda stated that Ellen in her employment with the army waited on the officers at Fort Gibson, she later learned that Ellen and George had married at Fort Sill, Indian Territory. She said that Ellen later came back to Fort Gibson at different times and left four children with her to take care of. Ellen left the boys Crawford, Clarence and the girl Georgia and later the youngest boy Luther. Georgia was the oldest of all the siblings. Amanda said all the children went by the surname of Goldsby. At the time of the interview, Amanda stated that all the children were dead except for Georgia, who married John Foreman and lived near Nowata, Oklahoma. She also said that everyone regarded George as a white man.

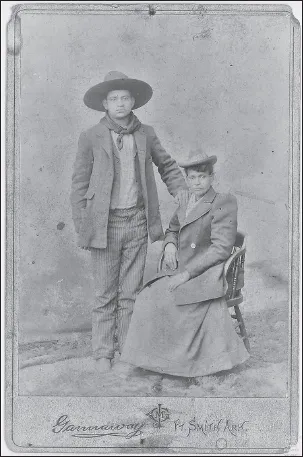

Cherokee Bill and father George Goldsby.

Ellen Lynch was interviewed by the pension board on February 3, 1912, she was 53-years-old at the time. She was born in February of 1859 and died December 17, 1932, in Fort Gibson, Oklahoma. Ellen stated that she was at one time the wife of George Goldsby, who afterwards went by the name of William Scott. They were married on July 4, 1874, at Fort Sill, Indian Territory, at the time she was fifteen years of age, George was twenty-nine.

Ellen stated that she had first met Goldsby at Fort Gibson, Cherokee Nation, in 1872. Goldsby at that time she stated was First Sergeant, Troop H, 10th U.S. Cavalry Regiment, one of the storied Buffalo Soldier units. Ellen went with the troop from Fort Gibson to Fort Sill as the regimental authenticated laundress of D Troop. Once in Fort Sill, Ellen said that Goldsby was transferred to Troop D.

Later, after marriage to Goldsby, but still working as the regimental laundress, the regiment was transferred to Fort Concho near San Angelo, Texas. Ellen stated in the deposition that while at Fort Concho, Goldsby was charged with inciting a riot in San Angelo and a warrant was drawn up for his arrest, which at that time he went AWOL before a trial could take place.

After this occurred, Ellen returned to Fort Gibson, and said George joined her after eight or nine months had elapsed. She said George only stayed in Fort Gibson for a few weeks, after he left, she said she never saw him again. Ellen said the year this took place was 1880.

Evidently, Ellen went back to the 10th U.S. Cavalry Regiment as an “authenticated” laundress. In a later deposition in June of 1923, she stated that after George left her she stayed with the regiment and the government gave her rations, transportation and living quarters wherever the 10th Cavalry was headquartered. Ellen said she was employed at Fort Concho and Fort Davis, Texas, Fort Grant and Fort Apache in Arizona.

According to the 1923 interview, Ellen next married a William Lynch on June 27, 1889, in Kansas City. Lynch was a private in Troop K, 9th U.S. Cavalry Regiment. They met at Fort Apache; Lynch was a ten-year veteran of the regiment and later mustered out. They got married in Kansas City, because they stopped there on their way to Fort Gibson. Ellen at this time had served about sixteen years in the employ of the U.S. army.

Cherokee Bill and his mother, Ellen.

In the interview with the examiner from the U.S. Pension Board, Ellen stated the following concerning George Goldsby:

. . . I was with him at Fort Concho, Texas and did not go away with him, but he left me there and I stayed there until 1880 when I got money to come back to Fort Gibson. I had four children by George Goldsby. They were Georgia Ellen Goldsby born July 13, 1874 at Fort Sill, I.T.; Crawford J. Goldsby, born at Fort Concho, Texas, February 8, 1876; Clarence Goldsby born at Fort Concho, Texas, September 27, 1877; and Luther Goldsby born at Fort Concho, Texas, August 30, 1879. . . . Goldsby was arrested by the Sheriff? Who went to Seneca, Missouri, and arrested Goldsby and kept him for three weeks waiting for the Texas authorities to come. They did not come and the Sheriff turned him loose and Goldsby went to Eureka Springs, Missouri. . . . Goldsby (George) was cooking at a hotel in Eureka Springs, Arkansas in 1880. . . . He (Goldsby) had 6 children by his next wi...