![]()

Chapter 1

Born To Slavery

Thomasville was founded as the county seat of rural Thomas County, Georgia in 1826. Today the city holds an annual Rose Festival and features plantations open to the public, a historic downtown, a large farmer’s market and a 320-year-old oak tree at the corner of Monroe and Crawford streets. It was designated a Great American Main Street City in 1998. However, there is a dark side to Thomasville—slavery.

The two aspects of Thomasville are reflected in its two cemeteries: the white cemetery is has neatly manicured grounds and well-kept graves while the black cemetery where blacks such as Henry Ossian Flipper and his family are buried is very shabby and poorly maintained.

Thomasville, with about 1,500 residents in 1856, was a prosperous town set against a backdrop of small farms and large plantations. The town was a minor business hub and a place where those with respiratory problems came to take a cure in the dry pine-scented air.

The McBain House offered board at fifteen dollars a month. A copy of either the Enterprise or the Reporter would have presented readers with differing political viewpoints. Broad Street, the principal thoroughfare, was lined with live oaks and well-kept flower gardens which exuded a lovely floral fragrance. However, at night residents were disturbed by the “miserable, hateful, hideous, horrible, abominable, ungodly and detestable” howling of dogs.2

Blacks, such as the Flipper family, were relegated to slave quarters. From sunrise to sunset, white farmers and black slaves drove horses, mules, and donkeys, hauling wagons full of vegetables, corn, wheat, sweet potatoes, molasses, tobacco, and that most important cash crop, cotton, into town.3

On March 21, a pleasant spring day, only a slight air of tension permeated the Rev. Reuben Luckey’s humble slave quarters. After all, the birth of a baby, particularly a black slave, was not much cause for anxiety other than as a piece of property. While the women went about their work, they comforted Isabella Buckhalter whose time had arrived. It was her first child, and her husband, Festus Flipper Sr., was in Virginia with his owner, Ephraim G. Ponder, a Thomasville alderman.

Ephraim had taken Festus Sr., along with several other slaves, to Virginia to serve an apprenticeship with a carriage trimmer. While these men were in training, he purchased new slaves and supervised their instruction. It appears that Ponder realized the freedom for slaves was not far off. By providing his slaves with training in useful crafts, they would be better able to cope with freedom and it s responsibilities.4

Although the Ponders and the Luckeys were among the more compassionate and benevolent of slave owners, just a year earlier, a Thomasville slave had been lynched for disobedience.

The Flippers’ first son, Henry Ossian, was born the same year as that another slave child, Booker T. Washington. Washington made his mark on American history by slowly progressing through the system of slavery and racial prejudice to freedom. Flipper’s life, while marked by peaks of spectacular success and high adventure, was often blemished by failure and rejection.

At the time of Flipper’s birth, Thomasville plantation owners and farmers depended on black slaves for a constant labor pool. By 1860, Thomas County, Georgia, had 4,522 whites and 6,244 slaves. There were only 405 white masters in Thomas County and only three of these men owned more than a hundred slaves.5

Henry’s mother, Isabella Buckhalter, was the “property” of Rev. Reuben H. Luckey, a Methodist minister in Thomasville. Luckey also served as president and secretary of the Board of Education. For six years, he was the principal of the Fletcher Institute, a school operated by Methodists and supported by Masons.6

Isabella and her two married sisters, Chloe and Hagar, took the name of their former master, Buckhalter, a practice common among slaves. Flipper was by his own description a mulatto, and the name Buckhalter may have reflected strains of German blood. Henry recalled that when Isabella’s relatives came into town on Sundays to attend church, they walked along the dirt roads with their stockings and shoes hanging around their necks. Upon reaching the church they would sit down and put on their shoes and stockings before going inside. Once outside after the service, shoes and stockings came off and “Away they would go for home.”7

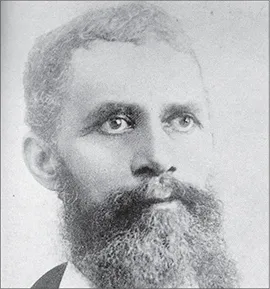

Festus Flipper, father of Henry Ossian Flipper.

Courtesy Thomas County Historical Society.

Isabella Buckhalter, mother of Henry Ossian Flipper

Courtesy Thomas County Historical Society.

In his later years, Henry did his best to fill in the family history, but he regretted that no one else had kept track of the early genealogy of his parents. His paternal grandmother, who he described as “a small woman and an octoroon” arrived in Atlanta in the late 1860s or early 1870s, but returned to Virginia before his West Point appointment in 1873.

His father Festus Flipper Sr. was born in 1832 at Guinea Station, a small town between Washington, D.C. and Richmond, Virginia. Festus Flipper appears to be related to a family headed by Joseph and Harriet Flippo in Caroline County, Virginia. Both Joseph Flippo in Virginia and Festus Flipper in Georgia had sons named Festus and Joseph.

In 1870, neighbors and probably relatives of Joseph and Harriet Flippo in Virginia included Walker and Patsy Taliaferro. The name—Philippi, Flippo and Flipper—derives from a family of Virginia slaveholders including Joseph, Gideon, Addison, and Littleton Flippo.

Although Festus took the name Flippo from his first owners, everyone on the Ponder estate called him Flipper. Since that time, the brothers and sisters of Festus Sr. retained the spelling of Flippo, but his descendants took the name of Flipper.

Festus Sr. had been the property of James Ponder until he was sold at auction in June of 1855 for $1,180 to James’s nephew Ephraim. The sale was held to settle the uncle’s estate.8 Ephraim Graham Ponder was a prominent financier in antebellum Georgia. After the Civil War, his Thomasville town house became the nucleus of Young’s Female College. His brothers, James and William, were prosperous Thomasville citizens. William, who owned Sunny Mill a large plantation, was an outspoken anti-secessionist.

In 1859, Ephraim moved his household to Atlanta, a metropolitan hub of the commerce and transportation. Atlanta, which had built railroads to bring in foodstuffs and export cotton, attracted bankers and served as the state capital.

While many urban slave owners provided their slaves with instruction in profitable crafts, few such as Ponder allowed his slaves to keep a large portion of their earnings. Most slave owners hired out their slaves or consigned them to plantation owners for work in the cotton fields. Usually all of this money passed from employer to master, and the slave, who was not physically abused, considered himself fortunate.

When the moment arrived to leave Thomasville, Festus Sr. implored Ponder not to separate him again from his wife, Isabella, three-year old Henry, and their new baby, Joseph Simeon. Ponder was sympathetic, but he did not have enough cash to acquire the whole family. He had just bought twenty-six acres of land on Marietta Road and built a house for himself and his young wife, along with slave quarters for his wards.

Nor could Rev. Luckey afford to purchase Festus Sr. at the high price asked by Ponder, but he, too, was sensitive to the family’s feelings. Demonstrating a remarkable amount of courage and individualism, Festus lent Ponder the money from his own savings, to buy the Flipper wife and children. Henry recalled, “The joy of the wife can be conceived—it cannot be expressed.”9 Ponder agreed to reimburse Festus when it was “convenient,” but it is doubtful that this loan was ever repaid.

When the Flipper family arrived in Atlanta, a class of select slave craftsmen had already joined the free artisans and tradesmen to form a black petit bourgeoisie. For the most part, they were mulattos with varying degrees of white blood, a result of “stable liaisons.”10

Ponder built a splendid stone two-storied house with a railed observation platform in the center of the roof. An elegant veranda overlooked the gardens, which were reputed to be among the finest in Atlanta. Standing on high ground, the house’s white-plastered walls glistened in the sunlight. At the rear of the home was a large kitchen. Separate slave-quarters were of substantial size. Along Marietta Road, Ponder constructed three large buildings where his slaves conducted their business and manufacturing functions. Except for the household slaves, Ponder allowed his slaves to practice their trades and hire out their own time as they wished. He refused to interfere in these business matters, except to collect his percentage of the profits. According to Henry:

Ponder Estate after Civil War destruction.

Photo Courtesy of Atlantic Historical Society.

Mr. Ponder would have absolutely nothing to do with their business other than to protect them. So that if anyone wanted any article of their manufacture they contracted with the workman and paid him his own price. These bond people were virtually free. They acquired and accumulated wealth, lived happily and needed only two other things to make them like other human beings, viz. absolute freedom and education.11

Slaves took orders for buggies, carriages, stagecoaches and carts, and the repair of these items, along with making boots and shoes to order. It would not be long before the influx of slave craftsmen and their employment aroused resentment among the white laborers of the region.

During the latter part of 1860, white citizens demanded official action against black businesses. The Atlanta City Council agreed that the employment of these slaves “operates very injurious” to the interests of its white citizen workers. A resolution was proposed that called for a tax for the ensuing year of $100 on any slave craftsman whose owner lived outside the city limits. A week later, the council tabled the resolution. Ponder, who was part of the problem, must have exerted considerable political influence.

At the same time, the prevailing mood in Thomas County was against immediate secession, and saw little of the firebrand secessionist movement. Unionists such as William Ponder were labeled “cooperationists” because they favored secession only if there was no other alternative and only if it was done en masse by cooperative action of all southern states. In November, the state legislature instructed the counties to elect delegates to a state convention where it would be determined whether or not Georgia seceded.

After a meeting in the Thomasville courthouse on December 15, delegates Samuel B. Spencer, A.H. Hansell, and William G. Ponder were elected to attend this convention. These three delegates were ready to secede only if the no other solution was available.13 However, the secessionists controlled the convention and carried the state. On January 19, 1861, Georgia declared itself free and independent of the Union.

While Ponder opposed slavery, he resented what he perceived as the “intolerant bigotry of New England hypocrites.” His father had purchased his first slaves from New England slave traders, who amassed a fortune by bringing blacks into the United States and selling them to southern planters.14

In retrospect, Ponder would have been better off if he had remained in Thomasville. The Civil War, which left Atlanta in fiery ruins, barely touched Thomas County. The only Yankee soldiers to tread on Thomas County soil, were the Union prisoners jailed in Andersonville. Thomas County did provide several companies of Confederate soldiers and its fertile farmland was an important source of sugar cane, corn and pork.

Ephraim’s personal troubles began when he married Ellen B. Gregory. “Beautiful, accomplished and wealthy” and fourteen years his junior, she took little interest in his projects, preferring to consort with the many men who caught her fancy. Flipper noted that as the “dissolute” mistress of the Ponder household, Ellen neglected the duties and functions of her station and devoted her attention to “illegitimate pleasures.”15

Her patient husband was reluctant to acknowledge the gossip surrounding his wife’s extra-marital affairs. On April 27, 1858, he indentured his slaves, “men, women, and children slaves of various darkness of complexion” to Ellen, “in consideration for the great love and affection he bore his wife.”16

Eventually her debauchery proved too unbearable for even Ponder. In October of 1861 he filed a divorce suit in the Fulton County, Georgia superior court. Ephraim charged Ellen with having committed adultery since 1854 with several men over a period of at least seven years. He also accused her of habitual drunkenness, threatening him with a gun, using abusive language, and treating him with the “utmost disrespect.”17

Their divorce petition indicates that the Ponders’ real wealth rested on the backs of their human property. Their estate was valued at $45,000 in slaves, but the elegant mansion was only worth $10,000. The couple separated at once, but the divorce proceedings dragged on for almost ten years. A humiliated and saddened Ephraim returned to his agricultural activities in Thomasville, while Ellen remained nominally in charge of the household in Atlanta.

Although she retained possession of the slaves, the divorce settlement stipulated that no slave could be sold without the mutual agreement of both Ephraim and Ellen. Thus, despite her constant threats to send them to “Red River” a detestable symbol of the slave block and cotton fields, none of her slaves were afraid of being sold. According to Flipper, they knew very well that the Ponders would never agree on anything.

The Georgia Penal Code of 1861 specified a fine and/or imprisonment at the discretion of the judge, for any perso...