![]()

An Encounter in Los Angeles

Rarely have two brothers been so close as Bob Simpson and his baby brother. I was born September 27, 1923, while Bob preceded me in this world on December 17, 1921. Growing up together, many people thought of us as twins, although the resemblance was not striking. Together we had attended Citizen’s Military Training Camp in the summer of 1940. It was rugged infantry training, and we were issued a 30.06 rifle, the Army’s standard weapon of the First World War. Bob took military training with greater zest than I demonstrated. Once Bob concluded that World War II was drawing nigh, he decided to enlist right away. After we returned from military camp, he decided to join the U.S. Marine Corps. Our mother was not anxious to have him do so, but he was not to be denied. Finally, our mother and father agreed to sign the necessary papers for him to enlist in the fall of 1940. After boot camp at the Marine Corps center in San Diego, Bob was sent to guard the U.S. Naval Air Station at Kanoehe on Oahu. He was promoted in rank to private first class and soon thereafter to the rank of corporal.

Things were not the same without the company of brother Bob in Copperas Cove. I always regretted that our paternal grandmother was so obviously devoted to me and much less so to Bob. Fortunately this did not adversely affect my relationship with my brother. He had the patience of Job. Bob enjoyed the camaraderie of serving in the Marines, and he wanted me to follow him. With the approach of war, I became convinced I that should join the U.S. Army Air Corps and become a pilot. The pay was much better, and one would gain invaluable knowledge if one could succeed in the aviation cadet program.

In 1941, I was still living at home in Copperas Cove. On December 7th I had been climbing a small mountain near our home. When I returned about two o’clock in the afternoon that day, I found a delegation of relatives and friends gathered by the radio. I could sense something serious had occurred. My mother was seated in the living room and was quietly weeping. The radio had reported that the Japanese had carried out their infamous sneak attack on Pearl Harbor in Hawaii. Communication was slow, and it was not known whether my brother Bob had survived. As news of the attack was being broadcast, the U.S. Naval Air Station at Kaneohe, about 15 miles from the Naval installation at Pearl Harbor, was frequently mentioned. There was unbearable anxiety in our small living room as we awaited news of Bob.

My brothers tried to place a telephone call to Bob but their efforts were to no avail. A long, slow week passed before we learned that Bob had escaped injury on December 7th.

I was a senior in high school and not required at that time to register for the draft. I wanted to immediately enlist on hearing of the devastation wrought by the Japanese. My mother insisted that I graduate from high school before joining the military, and at my age, I could not enlist without the signature of my parents. I completed high school that spring, and on June 5, 1942, I was sworn in as an aviation cadet. I was called to active service on November 11, 1942, and was immediately sent to Santa Ana, California, for flight training.

Meanwhile, Bob returned from Hawaii and was stationed at the Marine Corps station at San Diego, some 90 miles south of Santa Ana. We corresponded and resolved to see each other at the earliest possible opportunity. It had now been two years since he had left home, the longest span of time we had ever been apart. We found it difficult for both of us to get a three-day pass at the same time. Finally, I was allowed a weekend pass, but I did not have time to notify Bob in advance so that that we might meet.

At Santa Ana I boarded the single gauge railway passenger train, which carried me to the station at Los Angeles, where I was still about 100 miles north of San Diego. Train stations in those days were crowded with service men and women from all of the branches. I knew the chances of my running into my brother were slim to none. It would have been like finding a needle in a haystack. Getting off the train in Los Angeles I dared to speculate on the possibility I might encounter Bob on the streets of Los Angeles. It is hard to imagine the elation both of us felt when we ran right squarely into each other on the sidewalk outside the train station.

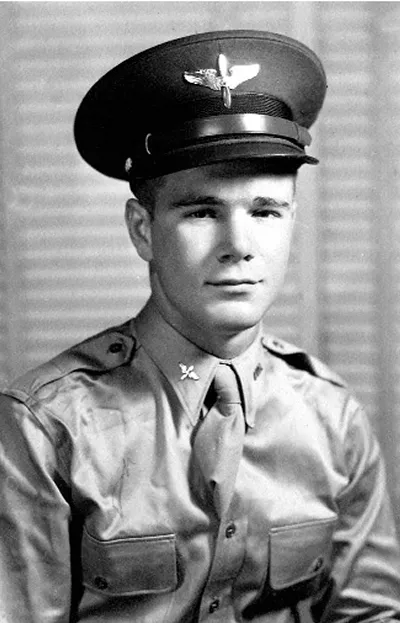

Jim as an aviation cadet on a two-day pass in Los Angeles, 1942.

I saw this tall handsome Marine approaching me and was shocked upon recognizing my hero and brother Bob G. Simpson. We hugged and danced on the streets of Los Angeles and then went to find a place for lunch. We talked incessantly, trying to bring each other up to date on the happenings since our last time together.

Soon we found a place where we could have our picture taken together. Then we wrote a letter to our parents enclosing the picture, which appears in these pages. A few weeks later I received another weekend pass and journeyed to the Marine Corp station at San Diego, where I stayed overnight in the barracks where Bob lived. We still could hardly believe our paths had crossed.

Army Air Corps turret repair school in Indianapolis. Jim on the left with three fellow soldiers.

I had a few more weeks of pre-flight school, after which I was sent to a small pilot training school in Blythe, California. Bob could not find any way to get sufficient leave to go back to Copperas Cove, and I was likewise unable to interrupt my own training. We were not to meet again for two years. In November, 1945, Bob was honorably discharged and returned home. I had been released the previous July. Needless to say there was much celebration at our family home in Copperas Cove when once more Bob and I were reunited.

Lana Turner and Me in Palm Springs

In June 1943 my dearest friend was a fellow Texan, Roy Lee Campbell, who hailed from Kenedy, Texas. If there was any person in our flight class at Blythe, California who was more country and unsophisticated than I was, it was my friend Roy Lee. He was my age, l8, and he had a vivid imagination. Somehow he became convinced that if he and I could find our way to the desert resort of Palm Springs, California, many memorable adventures would ensue.Indeed, Roy Lee was confident that if he and I journeyed to Palm Springs for the weekend, by Saturday night one of us would be in the arms of Lana Turner and the other in the embrace of Rita Hayworth. With great earnestness, he presented a plan to me.

I was so absorbed in the possibility I might earn the wings of a pilot and Second Lieutenant in the U.S. Air Force that I had given Roy’s plan no thought. Finally, after days of Roy Lee’s insistence, I cross-examined him about the proposal. Not only was I skeptical about enjoying the company of two Hollywood stars, but we did not even have a means of transportation to Palm Springs. How could we get there? Roy’s reply: “We’ll hitchhike.”

I pointed out that hitchhiking for an aviation cadet was an offense punishable by dismissal from the Aviation Cadet Program. I was listening to my fears while Roy Lee could only hear his hopes.

Finally, after a great deal of discussion, it was decided that the coming weekend would find us on the road to Palm Springs. We received a weekend pass and bummed a ride with a fellow cadet to the outskirts of Blythe, some 200 miles from Los Angeles. It was from the dusty shoulder of the highway that our journey would begin. According to Roy Lee, we were only hours away from being welcomed to the desert resort by Hollywood starlets.

We started hitchhiking along the desert highway, and soon I could see a U.S. Air Force staff car going the same direction as our destination. Was it really our lucky day? As the four-door 1940 Plymouth drew closer, I could see it bore a pennant on the bumper denoting the presence of a general officer. Suddenly my worst fears seemed imminent. A general would surely be aware of the regulation prohibiting hitchhiking as a means of transportation for future officers.

I told Roy we had now made a mess of things, that the general would soon arrange our court-martial, not to mention our dismissal from the flight program. I suggested to Roy that we should turn our back to oncoming traffic and pretend we indeed were not hitchhiking. We stepped lightly into the desert, trying to put as much real estate as possible between us and the general.

Our luck seemed to run out when we heard the screech of tires as the Plymouth came to a halt. Suddenly, we heard the sergeant driver bark out at us, “You men come over here! The general is offering you a ride in his car.”

Blood ran cold in the veins of the two prospective pilots. The courageous streak in Roy Lee disappeared as he made his way to be seated on the front seat next to the sergeant driver, relegating me to the back seat next to the general.

I could sense that the general was more than a little fascinated by these two youngsters who looked like they were playing hooky from high school. He inquired as to the purpose of our trip to Palm Springs. I tried to explain that we were stationed nearby at a primary training field, and we simply had a weekend off to explore. I noted from his uniform he was not an Air Force officer but indeed was in the armored division, giving me some faint hope that he might be unfamiliar with the rules against hitchhiking. As I told him our primary mission out on the desert was learning to fly airplanes, I could sense a feeling of astonishment wash over the general as he bowed his head in dismay. As he looked at us closely—two skinny, uneducated, and inexperienced teenagers—I fancied I could hear him mutter to himself: “Oh dear God, have we come to this? Are we this desperate?”

Eventually, I spotted a road sign advising that Palm Springs was 60 miles down the road. My hopes were buoyed up at the thought we might yet avoid detection of our nefarious scheme.

The general could not have been kinder as he told us he would be parking the staff car at a motor pool, and we would be welcome to share a taxicab with him at his expense. The presence of a general officer created quite a stir at the motor pool, and the three of us were granted a wide berth. When we reached his destination, I thanked the general profusely. Giving him a snappy salute, I departed his company, relieved that I was not intercepted by the military police and court-martialed.

However, with regard to the weekend’s primary mission, I must confess that neither Roy Lee nor I were destined to meet Lana Turner during our visit to Palm Springs. All’s well that ends well.

One a Day in Tampa Bay

The bonds that are forged in the crucible of war are probably the strongest bond known to mankind. That was certainly true for me and remains so now more than 60 years later.

It fell my lot to serve in one of the most decorated groups of its size in the history of the Second World War. Having little aptitude for landing airplanes during pilot training, I was assigned to a B-17 bomber ground crew before advancing to the position of navigator and bombardier on a crew of the B-26 medium bomber built by Martin in Baltimore, Maryland. The B-26 had an inauspicious beginning when early test flights were marked with numerous fatal accidents. The bomber became known variously as the Widow Maker, the Flying Prostitute, and other less fetching names.

Many authorities originally believed the aircraft was not air worthy. Some even said it was not even aerodynamically sound. It became so unsafe that it became the subject of an investigation by then-Senator Harry Truman’s War Preparedness Committee. During a 30-day testing period, 30 bombers were lost as a result of power failure on takeoff. The path of an aircraft taking off from MacDill Field, where the planes were tested, extended out over Tampa Bay. Often, as a result of insufficient power, the bomber and its six crew members ended up in Davy Jones’ locker. Suffice it to say, new crew members greeted their assignment to the B-26 with much trepidation.

The Truman Committee urged that the miscreant bomber be junked and be replaced by the B-25 and the A-20, aircraft that did not have the same unsavory reputation. History was to show it was fortunate that the Truman Committee recommendation was not followed. Instead, a plan was conceived to increase the wingspan of the B-26, and thus increase lift and stability. This and other changes made the bomber viable, and it was committed to combat over German-occupied terrain in Europe in April 1942, shortly after Pearl Harbor.

While in Florida, I met some interesting characters, including Bill Pehr from Denver. Bill became a dear friend and would remain so throughout the war. At one point, Bill was just a few days away from graduating as a rated pilot. He had all the requisites for becoming a great pilot, except for the fact that he had a bad temper. One day while Bill was at the controls, an instructor pilot chastised him severely, and Bill lost his temper. When he brought the training plane back to earth, he continued to exacerbate the situation by continuing to quarrel with the instructor, whereupon he was washed out of the pilot training program.

This did not improve his outlook on life, because like me, he was relegated to ground service. Prior to our service in a B-26 squadron, we were both members of a B-17 squadron at MacDill Field. Bill and I were placed in the armament section, maintaining machine guns, bomb racks, gun turrets, and the like. To us, the work was a crushing bore. Bill pointed out to me, however, that our job had one saving grace, and that was that you were fairly assured of dying of old age, not from combat with the enemy. I reasoned that I would rather risk being killed than to suffer the certainty of boredom. I told Bill we should both ask to be sent to aerial gunnery school.

Bill was a reluctant dragon. Although he resisted, he ended up joining me in making a request to the squadron adjutant that we be transferred into the flight echelon. The next day, we were notified that we were to be sent to Fort Myers for gunnery training. Upon graduation into a combat crew, we received a 10 day leave, after which we were ordered to report to a replacement training unit at Barksdale Field, Louisiana. Here, the various crew members, pilot, co-pilot, bombardier, top turret gunner, and tail gunner, were formed into crews for further training. Classified as air combat crews, we were exempt from such tasks as guard duty and kitchen police. We were paid 50 percent extra as flying pay. All in all, life was much improved after leaving the B-17 squadron and joining the air crew in a B-26 squadron. There was more excitement, coupled with more danger.

Bill and I went on to join a great unit known as 451st Bombardment Squadron. Later in England, we would discover that boredom was rarely a problem in our squadron.

While I was in aerial gunner school at Fort Myers, I met one of the most interesting and colorful characters I was ever to meet. His name was Roland. Unlike me, who hailed from small town Texas, Roland spoke with an accent. It was pure Bronx. Roland had grown up in eastern New York State. He was a bright, earnest fellow, very cordial, and of unfailing good humor. But he was not much of a marksman. Indeed, he couldn’t hit the floor with his hat.

Weekend pass from Barksdale Field, Louisiana, 1944. From the left, Joe Simpson (Jim’s older brother), Jim, Roy Cooper, and Louis Dewald. Cooper was Jim’s high school tennis partner, and Dewald was then a Naval ROTC student at the University of Texas.

Louis Dewald, Jim, and Roy Cooper, 1944.

We were introduced to aerial gunnery through skeet shooting. Clay pigeons, or disks, were launched into the air as targets and we were required to shoot them with a shotgun. Usually, in a morning of shooting, each gunnery candidate would fire on 25 clay birds. To break 18 out of the 25 w...