![]()

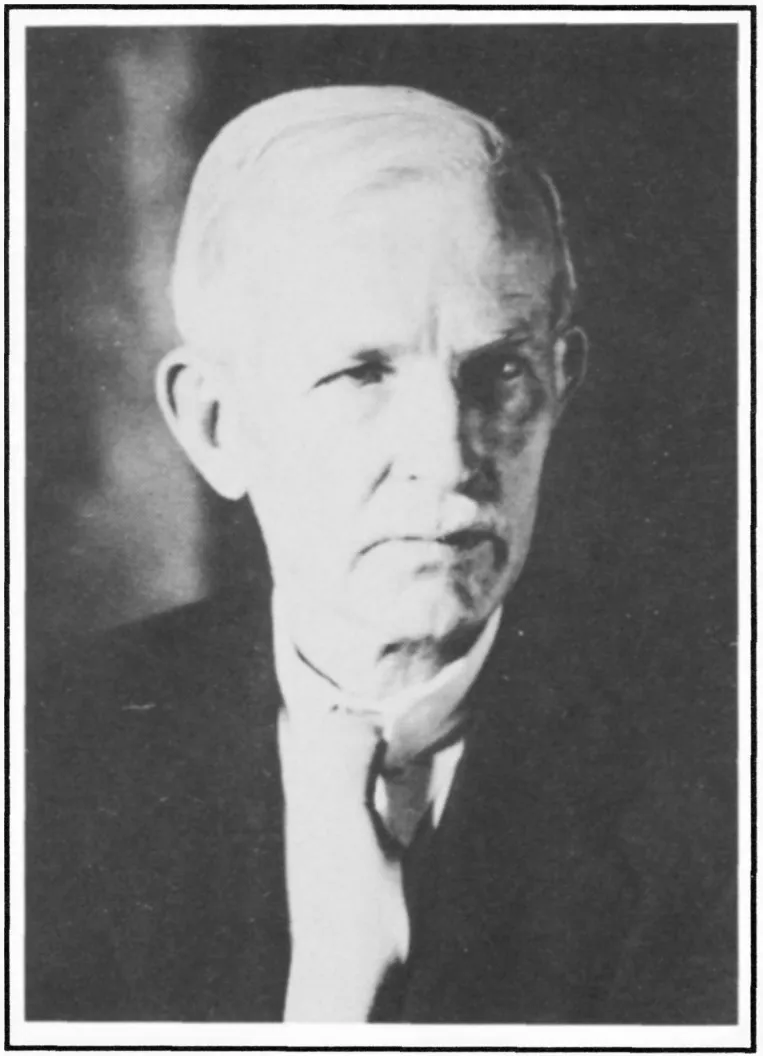

Eugene Manlove Rhodes, age 74: taken two weeks prior to his death in June, 1934.

PART ONE

EUGENE MANLOVE RHODES, 1869 - 1934

Chronicler of the Southwest

The Setting

New Mexico is as much a state of mind as it is a state of the Union. To the enchantable it truly is a “Land of Enchantment”. To the prosaic it offers nothing but wind, dust, heat and bitter winter chills. It is as different from its sister state, Arizona, as California is different from Oregon. Its appeal is similar to the appeal of horseradish or bagpipe music. You either hate it or love it. There’s no “sort of” about it.

New Mexico offers wide open expanses framed by majestic snow covered mountains, strangely beautiful rock formations, clear mountain streams and desert rivers that sink from sight. You can leave dry dusty Albuquerque and, in a matter of minutes, be in knee deep snow among tall pines in the Sandia Range.

In probably no other state is history so much a part of daily life. Remnants of New Mexico’s violent and turbulent past are on every hand. Towns like Lincoln, Tularosa and Santa Fe appear much the same as they did a hundred years ago, except for the power lines strung overhead, and the paving underfoot. You can almost hear and expect to see, the mountain men, Indians and Spanish soldiers in the plaza in front of the Governor’s Palace at Santa Fe. The blending of American, Pueblo Indian and Mexican cultures, in the last 175 years, has resulted in a rich, colorful and extremely inviting life style. The Pueblo Indians remain as mysterious and remote a society as ever, but their haunting architecture is copied over and over by Anglos who are so spellbound by it.

New Mexico today is still largely unoccupied as you will learn should you experience car trouble far from the city. In the 1880’s, it was almost as geographically isolated as the moon’s surface. Though crossed by rail lines in 1883, New Mexico was devoid of any roads save wagon tracks and horse trails. Citizens had to be self sufficient and innovative to survive. Trips to the store sometimes occurred only once or twice a year. Diet was confined usually to biscuits, beans and beef (sometimes from another man’s herd) garnished with chilies and what vegetables the ranch wife was able to grow in a garden she didn’t have time to tend. In that time, New Mexico was, as someone said, “Great for men, horses and dogs, but hell on women and kids”.

![]()

Chapter 1

The Forming Years

At noon on a hot dusty day in 1883, three sixteen year old boys stood on the windswept shoulder of a Southern New Mexico mountain admiring their handiwork. They were nearly men; wiry lads with stringy muscles and calloused hands. Their dirty faces reflected a combination of weariness and satisfaction. As they packed their tools and tightened cinches, they viewed with a great deal of pride the product of their joint efforts, a simple native stone cabin.

Hired by Pres Lewis, the rancher upon whose homestead they stood, the three, in a week’s labor punctuated by high jinks and hilarity, had built a house. Crude and rough though it was, it would stand for many years to shelter its owner from icy blasts of winter and the hot winds of summer. Its ruins can still be seen on Animas Creek, northeast of Hillsboro.

Having made their last joke, flung their last jibe, their laughter fading in the wind, the three shook hands, climbed on their horses and moved away. Two headed west. They were soon out of sight. The third, after a last long look at the cabin, headed his horse eastward, toward Engle, and home.

The next day the two westbound boys were ambushed by a band of Geronimo’s Apache reservation jumpers and brutally slain. One died with his own crowbar driven through his head.

The eastbound boy was destined to become one of the Southwest’s most skilled storytellers. His name was Eugene Manlove Rhodes.

It is an interesting comment on rural American nineteenth century society that three sixteen-year-old boys would be entrusted to build a permanent dwelling, be it ever so humble. At a time when family survival meant dawn-to-dusk labor for all, boys became men long before whiskers appeared. Gene Rhodes, already an accomplished well digger at thirteen, stonemason and roadbuilder at sixteen, was a prime source of income for the Rhodes family. In his middle teens, Gene also worked as a swamper for a freight rig, caring for the horses, their harness and the rolling stock. He served for eighteen months as a civilian guide for the cavalry out of Fort Stanton in its vain efforts to capture ancient Nana, one of the last Apache war chiefs to terrorize ranchers in the early 1880’s.

Eugene Manlove Rhodes

Gene Rhodes, born on a dry farm in Nebraska in 1869, came to New Mexico with his parents in 1881. That was the year Pat Garrett took the life of Billy the Kid, three years after the McSween-Murphy feud was ended in Lincoln. Lew Wallace, author of BEN HUR, sat in the territorial governor’s chair in Santa Fe.

Gene took to the hard life in New Mexico like a kitten takes to cream. A slender handsome youth of somewhat less than average size and suffering from a speech handicap, (he never could pronounce “Rhodes” distinctly) he made up in sheer grit, determination and a monumental wit for his physical shortcomings. Although small in stature, he never lacked the important ingredient, courage. If the occasion warranted it, and it often did in the days of his youth, Gene would fight with joy in his heart and a gleam in his eye. That is not to say he never lost a fight. He lost many of them. But if he was able, he always bounced back with a grin, ready for more. Many of the men Gene fought gave up in disgust because he wouldn’t stay down.

In his declining years, Gene once confessed to a friend that he had been involved in 65 fist fights during his lifetime.

Gene’s father, Colonel Hinman Rhodes, distinguished himself on the battlefield with honor and great courage during the Civil War but seemed destined to fail at every peacetime business venture he undertook. He tried dry farming; crops failed. He tried selling sewing machines door-to-door on the hot dusty roads of southeastern Kansas. He combined a prodigious capacity for sustaining physical effort and a keen intellect but seemed to lack commercial shrewdness. Unsuccessful in his attempts to provide for his family, he evidently followed someone’s well meaning advice and moved to New Mexico. He homesteaded a ranch near the town of Engle, at that time a bustling railroad and cattle shipping center in south central New Mexico. Engle has long since disappeared but it was the center of Gene’s world for a number of years. Colonel Rhodes worked as a miner, often developing the claims of others.

Gene spent a great deal of time in his early teens working with his father. He acquired considerable skill in mining, stonemasonry, drilling and use of explosives. His well digging ability became much in demand in the area around Engle. He was once called upon to clear out a one-hundred-sixty-five foot well whose walls had partially collapsed. In addition he was the builder of the first road from Engle to Tularosa, over the San Andres mountains, punching through a pass that bore his name, Rhodes’ Pass. This road is no longer to be found on any map since much of it crossed the White Sands Proving Grounds and was later closed to the public.

At sixteen Gene found his first love, horse wrangling. He gave up his masonry work and well drilling to become a top-of-the-line horseman. He quickly became a man who could do anything with a horse. He not only rode and broke any bronc from the sorriest scrub to the wildest range stallion at hand, but he made it seem so easy. He almost became a legend in his own time. His employment on local ranches, including the Bar Cross Ranch, came about because of his skill with horses. He was never a skilled cowman.

At nineteen, in 1888, Gene’s skills and general knowledge acquired through extensive reading, enabled him to gain entrance into what is now called College of the Pacific, located in Stockton, California. At that time it was known as The University of the Pacific, and was located at San Jose, California.

Why Gene selected this, a Methodist school, so far from his beloved New Mexico, is not known. It is known, however, that his mother was a staunch Methodist. At any rate, it provided Gene with some much needed socializing experiences and was the one time in his younger days when he could be and act young. It was, in his own words,’’...the happiest of my life. Not one care, not one unhappy moment...I had never known any boys. Just rough men. I had my youth in one deep, priceless draught.”

Gene had been forced by financial circumstances into manhood at thirteen, had done a man’s work since that time. This then was his one chance to be a boy for a time. He engaged in athletic events, he joined the Rhyzomian Literary Society and was among the list of officers the second year as “critic.” His first published works, unsigned, appeared in the college newspaper.

During the summer of 1889, Gene joined harvest crews and roamed the Salinas Valley from Salinas to King City working on the threshing rigs as the wheat crop ripened in the hot California sunshine.

Rhodes family tradition has it that Gene borrowed $50.00 from his father to get himself to California and enrolled. The rest of his expenses for two years, he earned himself.

One close friend he made at college was indirectly to have a profound impact on Gene’s future. His name was Sydney Martin Chynoweth. He graduated from University of the Pacific in 1890, the same year Gene returned to New Mexico. He either accompanied Gene home, or followed him soon after. He went to work the following fall as teacher of the one room school at Alto in Lincoln County.

Gene’s father was then Agent for the Mescalero Apache Reservation and he appointed Gene as Reservation Farmer, a decision he was later to regret when a political faction from Santa Fe, the notorious “Santa Fe Ring,” worked to get him removed. One of the charges made against him was nepotism.

On a dark night in early February, 1891, Gene and a friend, on their way home from an evening social function, were attacked by a Doña Ana County deputy sheriff and a seven man posse. This group did not identify itself, but called out for the boys to stop from the shadows of the cottonwoods that lined the street. Gene responded by jumping into the middle of the posse, fists flying. He was nearly killed. A doctor friend later counted thirteen head wounds from pistol whipping. A bullet fired at him traveled across his skull under his scalp.

The Rio Grande Republican, a newspaper owned by a member of the Santa Fe Ring, reported that Gene was “furiously drunk”. Colonel Rhodes contended that the incident was purely an effort to put him in disrepute with the Department of Indian Affairs.

Gene was charged with “Resisting an Officer,” and “Drawing a Deadly Weapon” The case was moved to Sierra County and the charges were dismissed.

In February, 1891, Gene was released as Reservation Farmer and Syd Chynoweth was confirmed in his place. In April 1891 Gene took over Syd’s job as teacher and completed the school year. He was not rehired, but went back to wrangling horses for local ranchers.

Eventually he wound up working for the Bar Cross Ranch, herding horses and working cattle. By common consensus, including his own, Gene was never a top line cowman. He carried his weight, but his heart wasn’t in it. He went with what he knew, and liked, and that was horses, reading, and poker. He homesteaded 80 acres around a spring in the San Andres mountains, built a rough cabin and corrals and leased it to Bar Cross for a horse watering camp. The money from this transaction went, as did most of the money he made, to his parents. Later, he tried horse ranching, trapping wild horses and rough breaking them to sell when you could hardly even give a good horse away. Which brings us to an episode in Gene’s life that demonstrates a facet of his personality, and which he later used as the basis for a story, (Loved I Not Honor More), his sixth published piece of fiction.

Word came to Gene, at a time when he seemed to owe everyone money, that a buyer was paying top money ($25.00) for rough broken mounts in El Paso, Texas. All Gene had was lots of horses. He saw a chance to move some stock and get some creditors off his neck at the same time, which he badly needed to do. He forthwith rounded up the best of his herd and lit a shuck for El Paso.

When he arrived, Gene was dumbfounded to learn that the buyer was an English army officer purchasing moun...