![]()

CHAPTER 1

THE DISCOVERY

The recorded history of New Mexico had its beginnings as the result of an event which occurred some 36 years after the discovery of the New World. In the year 1528, a Spanish ship was blown off course and wrecked near the site of present-day Galveston. The survivors were part of the ill-fated expedition to Florida of the Spanish conquistador, Panfilo de Narvaez. But Texas proved no more hospitable to the Spanish than Florida. Hunger, exposure and Indian attacks took their toll, drastically reducing the number of survivors to fifteen. Soon only four men remained of the hardy group of Spanish adventurers who had set out in search of God, Glory, and Gold.

One of these men, Alvar Nunez Cabeza de Vaca, was destined to be the first white man ever to set foot in New Mexico. He was accompanied by an Arabian slave of Morocco, Esteban (Estebanico). Cabeza de Vaca was typical of the Spaniards who came to the New World to make a fortune. Like other conquistadors, he was willing to endure fantastic hardships in pursuit of his goal. His eight-year odyssey through Texas and New Mexico has come down to us in the annals of the Conquest as a feat of endurance on a par with the exploits of more famous conquerors.

The four castaways began their westward trek unaware of the hazards that lay in store for them. Although their knowledge of the geography of the region was extremely primitive, they were sustained by the vague hope that somewhere to the west lay the frontier outposts of the Viceroyalty of New Spain. As they traveled westward through the trackless wastes of northern Texas, they repeatedly fell into the hands of various Indian tribes.

Their odyssey began to follow a pattern. The Indians first captured and enslaved the Spaniards. Gradually, however, due to their knowledge of European medicine and medical techniques, they won the confidence of their Indian captors and were given the respect due to healers and medicine men. Eventually, they either escaped or were granted their freedom by their admiring hosts. Upon being freed from one Indian group, they pushed westward only to be enslaved once again by another tribe. And thus the slow process of either escaping or winning their captors’ confidence started all over again. Eventually, they made their way into southeastern New Mexico at a point close to the modern town of Carlsbad. They followed the Pecos River for some distance before striking westward and crossing the Rio Grande near present-day El Paso. Finally, in 1536, they arrived at the northern Spanish garrison of Culiacan.

Dressed in skins and burnt by the sun and the wind, they presented a curious sight to the townspeople. But it was their stories of untold riches lying to the north which aroused the popular interest. Cabeza de Vaca was ordered to go to Mexico City to relate these wonders to the Viceroy, Antonio de Mendoza, the shrewd ruler of New Spain. De Vaca told him of the Seven Golden Cities that he had seen during his sojourn in the North. He spoke of large populations of sedentary Indians waiting to be converted to the Christian faith, and of signs of rich lodes of gold, antimony, iron, copper and other metals. These tales were enough to convince the Spanish authorities of the necessity of pushing beyond the warlike Chichimec Indians of northern Mexico and expanding the confines of New Spain to encompass the vast area which became known as New Mexico.

The sixteenth-century Spaniard was typified by Cervantes in the fictional Don Quijote de la Mancha and his companion, Sancho Panza. In these two individuals, Cervantes portrayed the Spanish character, at once practical, yet profoundly mystical. It was this schizophrenic trait which sent the hardheaded conquistadors chasing after chimerical legends: the Fountain of Youth, El Dorado, Quivira, and the Seven Cities of Cibola. In 1536, the reports of Cabeza de Vaca of the fabled golden cities in New Mexico quickly spread, firing the imagination of the youthful soldiers and adventurers of the Viceroyalty of New Spain. However, before launching a major expedition into the region, Antonio de Mendoza, an extremely cautious ruler, decided to send a fact-finding expedition northward to verify the truth of the reports.

His first step was to find a worthy leader of the proposed expedition. Cabeza de Vaca himself declined the offer and Estebanico, despite his qualifications, was precluded from commanding Spaniards due to his status as a slave and a non-Christian. After considering several alternates, Mendoza finally settled on a Franciscan friar who had had considerable experience among the Indians and possessed the physical stamina necessary for such an undertaking. He had accompanied the conquistadors to Santo Domingo and Peru and had reputedly walked from Guatemala to Mexico City to report to the Viceroy on the ill-treatment of Indians by conquistadors in South America. In his commission from the Viceroy, Fray Marcos was instructed to convey to the Indians of the North the promises of Charles V, King of Spain, that they would be treated humanely and that anyone who abused them would be severely punished. These promises, as subsequent events would prove, were more honored in the breach than in the observance. However, such instructions were no doubt given to the leader of the expedition in order to please the Spanish sovereign who was in the process of issuing the New Laws aimed at curtailing the abuse of Indian labor by unscrupulous conquistadors.

Fray Marcos was ordered to make detailed studies of the demographic characteristics of the area as well as to record the geography, flora, and fauna of the northern regions. After preliminary preparations, the friar, accompanied by Estebanico as guide, went north to the Spanish frontier town of Culiacan. There he consulted with the Governor, the youthful Don Vasquez de Coronado, who told him of his own ambition to make such an expedition—an ambition he would later realize in the famous ‘entrada' into New Mexico in 1540.

Finally, on March 7, 1539, the expedition got under way. In a letter to Viceroy Mendoza, Coronado reported: “Fray Marcos, his friend (Fray Onorato), the Negro and other slaves and Indians whom I had given them departed after twelve days devoted to their preparations." From Culiacan northward along the trail blazed by de Vaca, the dour Fray Marcos, dressed in the Franciscan habit of coarse Zaragosa cloth, trudged along accompanied by a few impoverished Indian servants. In contrast, Estebanico, flaunting his promise of obedience, impatiently pressed ahead. Boasting the trappings and entourage of a rich man and decked out flamboyantly in feathers, plumes, turquoise, coral, and tinkling bells, the Moorish slave led his triumphal procession northward toward the tragic fate which awaited him.

Along the way, he proved to be a constant thorn in the side of his superior. Fray Marcos reported that he indulged in all manner of vice: drinking and carousing, practicing heathenish medicine rites and even simulating the Church’s sacramental rituals by solemnly anointing the sick with the sign of the cross. As a consequence, Fray Marcos decided to detach himself as much as possible from the company of the Moor, instructing him to form the vanguard of the main party by several days distance. A simple code of communication was devised. The Moor was told that if he encountered a city of moderate size, he should send back by Indian messenger a cross the size of a man’s hand. If he should sight a large city, he should send back two crosses. But if he should discover a city comparable to the great cities of the Aztec Empire, he should send back a large cross. In less than five days, an Indian messenger appeared bearing a cross the size of a man as an indication of the importance of Estebanico’s findings. The messenger also conveyed to the priest the news that they were on the brink of the great discovery of the Cities of Cibola which were familiar to the Indians with whom Estebanico had made contact. And to lend credence to this claim, another messenger arrived forty eight hours later carrying an equally large cross and bearing the injunction from Estebanico that the friar should hasten to join him. Fray Marcos was suitably impressed and immediately set out to overtake the advance party.

But the friar was unsuccessful in his efforts to catch up with his recalcitrant guide; day after day, his party pushed ahead but they were unable to contact the illusive Moor. It has been suggested that Estebanico planned it so in the hopes of being the first to make the great discovery of the Golden Cities and thus win fame and fortune for himself. However, furious as he was with his wily subordinate, Fray Marcos was forced to admit in his subsequent account of the journey that Estebanico had smoothed the way for him. As he traveled from village to village, he was received with respect and provided with an abundance of food.

Finally, after several weeks of such progress, the friar’s group encountered the remnants of Estebanico’s scouting party. Wounded and disheartened, the survivors told the priest of how they had arrived at a marvelous city situated at the foot of a giant mound. Based on later computations this “city” must have been Hawikuh, one of the Zuni pueblos in western New Mexico.

But Estebanico and his entourage had not been well received. His messengers had been ordered out of the city and charged upon pain of death not to return. Perhaps the reasons for this hostile response to the Moor’s peaceful overtures sprang from the fact that the Zunis had recently received news of Spanish slaving activities among Mexico’s West Coast Indians. But Estabanico, throwing caution to the winds, scoffed at the threat and boldly marched up to the entrance of the pueblo. This act of defiance proved to be his undoing, for he was immediately taken captive and held for interrogation. Upon learning that two white men, representatives of a powerful king, were following, his interrogators believed him to be a spy for a hostile force and decided to kill him. They swiftly carried out the execution of the Moor and to prove he was not immortal as some Indians claimed, his body was chopped into little pieces and bits of bone and dried flesh were distributed among the neighboring tribes with the admonition to kill any intruder who should venture into their territory.

When he learned of Estebanico’s grizzly fate, Fray Marcos hastened back to Mexico City with the dubious report that he had indeed seen the Cibola and had witnessed with his own eyes the brilliance of those Golden Cities as they reflected the light of the evening sun.

Why did Fray Marcos de Niza insist in his report to the Viceroy that he had discovered the Cities of Cibola? Some historians are of the opinion that the good friar was convinced that he had really viewed the fabled cities. After learning of Estebanico’s murder, he claimed that he approached the Zuni pueblos and without alerting the inhabitants, cautiously viewed the towns from the safe distance of some nearby hills. Perhaps he saw the strings of corn drying on the flatroofed adobe houses and mistook the glint of the sun as reflecting gold. His fertile imagination was able to supply the rest of his story.

However, a more likely historical opinion states that Fray Marcos never actually saw New Mexico, but rather turned back before reaching the present international boundary line. Historians have presented convincing proof that he could not possibly have had time to cover the vast distances he claimed to have traveled. It has also been suggested by some scholars that maybe even Viceroy Mendoza himself was implicated in a plot to assure a subsequent major expedition and had instructed the friar to return from his fact-finding mission with a favorable report, irrespective of what he actually found in the North. Whether or not this was so, one fact is certain, the priest’s report sparked exaggerated stories of his discoveries. According to a rumor which soon spread, the people of New Mexico wore belts of gold and had successfully domesticated camels, cows and even the mythical unicorn. The official outcome of Fray Marcos' report was a massive effort to prepare a major expedition under the leadership of Francisco Vasquez de Coronado, the youthful governor of Nueva Galicia. Its purpose would be the expansion of Spanish dominion into the ‘terra incognita’ of the northern regions.

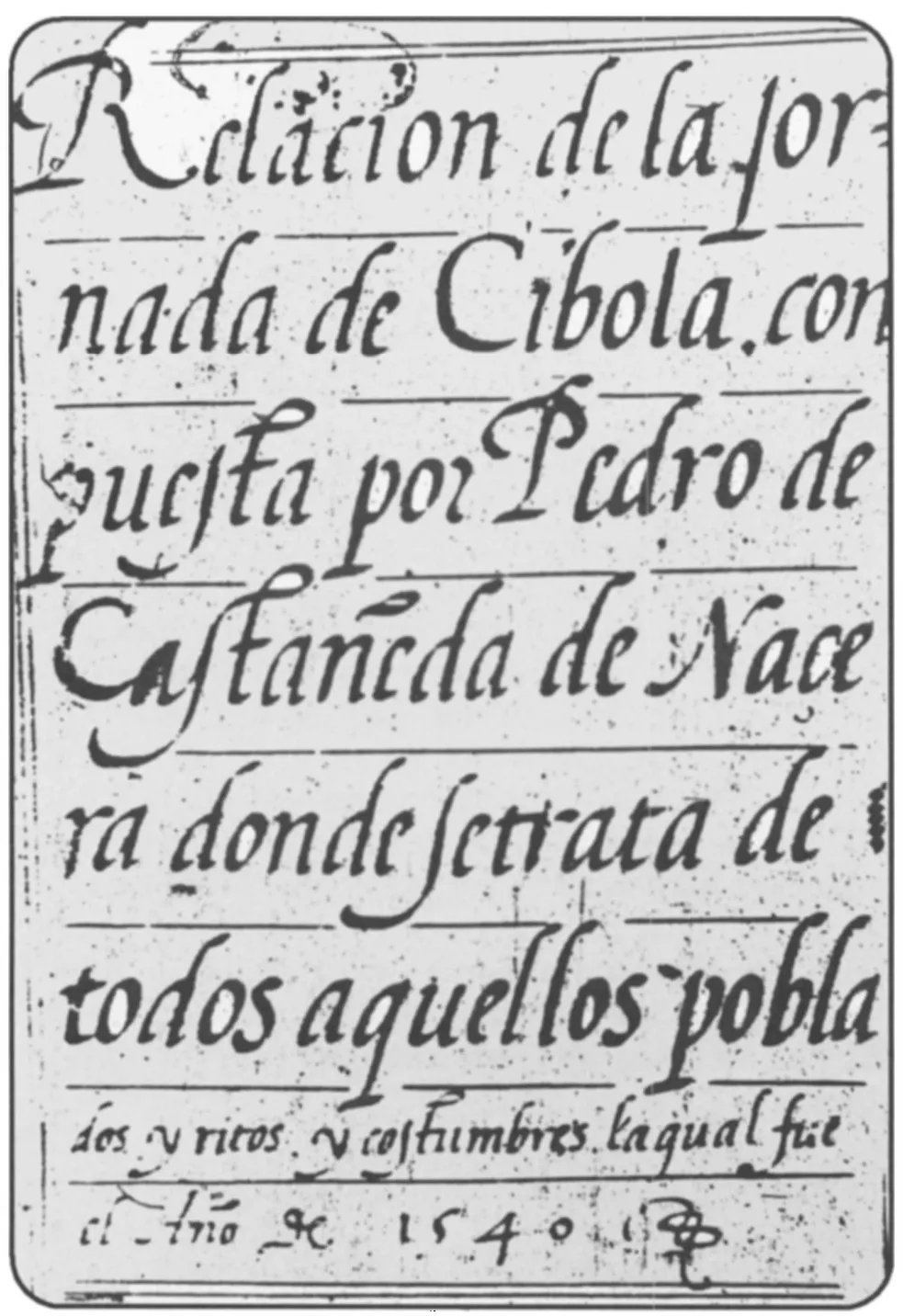

Figure 2: Account of the 1540 expedition of Don Francisco de Coronado, written by Pedro Castaneda de Nagera. Miscellaneous Spanish Archives. New Mexico State Records Center and Archives.

![]()

CHAPTER 2

THE EXPLORATION

Francisco Vasquez de Coronado had sailed to the New World with Viceroy Mendoza and possessed many influential friends at the Spanish court who could attest to his leadership abilities. But perhaps more important than his undoubted capabilities as a leader, was the fact that he was able to finance the proposed expedition. Spanish law dictated that the royal treasury would only provide for outfitting the contingent of priests designated to accompany the expedition and that all other costs must be borne by the sponsors of the venture.

Though himself only moderately wealthy, Coronado had married a rich woman whose fortune he proceeded to invest in outfitting his expedition. As far as he was concerned, this was to be money well spent, for the return on his investment in terms of gold, silver, land and Indian laborers would be worth the initial cash outlay.

All in all, it was a business venture with the profits to be shared in varying degrees by the investors. The estimated cost of the expedition in modern currency was about a million dollars.

Coronado found little difficulty in recruiting members for his enterprise. Young men, many of them still in their teens, pawned what few valuables they possessed in order to raise the money to pay for their personal equipment. Unemployed soldiers, adventurers and youthful grandees flocked to Compostela, the capital of Nueva Galicia, to join in the feverish preparations for the great expedition. They were inspired by visions of wealth and adventure which awaited them in New Mexico.

According to the most accurate estimates, the expedition was composed of approximately 235 Spaniards who possessed horses. They wore the steel or leather armor of the Spanish hidalgo and were armed with guns, crossbows and a variety of swords and daggers. Besides those fortunate enough to own horses, there were about 62 foot soldiers similarly accoutered and as many as 1,000 Indians accompanying the expedition as porters and livestock tenders. And since the expedition was a missionary enterprise as well as a business venture, a group of clerics accompanied the Spanish conquistadors under the tutelage of the ubiquitous Fray Marcos.

An air of optimism prevailed at Compostela, the preparations for the journey reflecting the gala spirits with which the young adventurers faced the future. Finally, with all preparations completed, Coronado led his expedition...