![]()

Part One

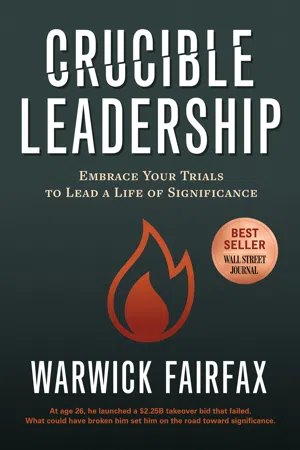

EMBRACE YOUR CRUCIBLE

Without exception, any study into the life of people who lead and live with impact will reveal this truth: their lives have been marked by challenging experiences, which have refined and shaped them. These “crucible moments” provide opportunities to reflect, re-assess, and redefine our identity, purpose, and vision in life and leadership.

Sometimes the crucible moment was the result of personal failure. Perhaps it was due to forces beyond our control. And perhaps it was a combination of the two. Regardless, these moments bring us to crucial crossroads in our lives and provide invaluable opportunities to take stock of ourselves. They lead each of us to deal with this foundational question that will determine the quality of our leadership and the trajectory of our lives:

Will the flames of a crucible experience consume us or will they be a refining fire from which we emerge purified, solidified, and forged with purpose?

Crucibles make or break a leader; we are never the same after going through such an experience. What is a crucible? According to the Oxford English Dictionary, a crucible is a container in which metals or other substances are melted or subjected to extremely high temperatures. But the secondary meaning is what this book is all about: “a severe trial in which different elements interact to produce something new.”

It’s a situation that produces a strong test of character. A painful life experience of failure or loss. A time when we are put through the fires of a life-altering trial and forever changed. Through a crucible, we may become a better person and grow, or we may be destroyed. The choice is ours.

This is the essence of any crucible. We have to ask ourselves: Am I going to let this situation destroy me, or am I going to learn from it? Will I become bitter at the injustice of it all, or will the accusations and unfair circumstances make me a better person?

In this first section, we will explore what it means to embrace the crucible moments of our lives and leverage them to be our best selves. Understanding how we’ve been refined will help us understand who we truly are, so we can move forward from crucible moments and lead lives of impact and significance.

![]()

Chapter 1

MY CRUCIBLE

So much of the cultural narrative about leadership is how success breeds success. The problem is that, for most of us, our paths haven’t always been on a straight progression.

When I was born in Australia in 1960, I was heralded as the heir apparent who would one day lead the family media business. I would be the fifth generation in the business founded in Sydney by my great-great-grandfather, John Fairfax, when he bought the Sydney Morning Herald in 1841. While I was growing up, John Fairfax Ltd. was a large, diversified media company that included newspapers, television stations, radio stations, magazines, and newsprint mills.

I was a child from the third marriage of my father, Sir Warwick Fairfax, to my mother, Lady Mary Fairfax. When we were living in England for about a year in the late 1960s, my parents adopted my younger sister and brother, Anna and Charles. I also have half and stepsiblings from my parents’ previous marriages, so when people ask me how many brothers and sisters I have, the answer is complex! From my father’s first marriage, there was a daughter and a son, Caroline and James. From his second marriage, there was a daughter, Annalise, and a stepson, Alan Anderson. My mother also had a son, Garth, from her first marriage.

The family dynasty was founded in the Victorian era and managed to retain many of that time period’s values into modern times. The custom was that only male children would go into the family business, and of those, typically only the older sons. My father asked his oldest son, my half-brother James, to join the business in the 1950s and gave James some of his shares to lessen the impact of estate taxes. But by agreement, the bulk of James’s shares would come to me one day. (I was the next son after James, who was more than twenty-five years older than me.) Adding to the pressure for me to join the company was the fact that James never married and did not have children. My father’s cousin, Sir Vincent Fairfax, also had a significant shareholding. His son, John B. Fairfax, would also join the company.

For my father, whose family line had more shares than other family members, keeping our line going was very important. Thus, I was seen by my father—indeed by both of my parents—as destined one day to become the managing director or chairman. Since I stood to inherit my father’s shares and the bulk of my brother James’s shares, I would also be the leading shareholder among the family.

I well understood my parents’ and family’s expectations, both spoken and unspoken. I did everything I could to make them proud, to be worthy of the mantle, and to live up to their expectations. I worked hard at school. Like my grandfather, father, older brother, and other relatives, I went to Oxford University. After graduating, I worked on Wall Street at Chase Manhattan Bank then went to Harvard Business School, graduating with a Master of Business Administration (MBA).

My father died in January 1987 when I was twenty-six, while I was in my second year at Harvard Business School. After his death, rumors were flying that our family company might be taken over. Management was making decisions I thought were questionable. I had concerns over whether the company was being run in line with the ideals of the founder.

How would I respond?

High Stakes, High Expectations

My family, especially my parents, looked to me to carry on the traditions of the family and the family name. They expected me to go into the family business, help it continue to exist, and pass it on intact—and hopefully greater—to the next generation.

What made it tougher, and the expectations higher, was that this was no ordinary company making, say, widgets. John Fairfax Ltd. was a media company that played a vital part in the nation. Some people go into public service to improve their nation, or others go into the military to defend their country. My family saw its role in the newspaper business in a similar vein: to speak truth to power and uphold those who were trying to make Australia a better place. This was more than a business. It was a sacred cause.

Another aspect that raised the stakes for me was the tradition in our family of preserving the ideals of the company’s founder, John Fairfax. It was not only important that the company be successful and do its job well; the way it did its job mattered to me. In my vision, a newspaper company should not be a place of cynical journalism that sees all politicians and businesspeople as corrupt, just waiting to be found out. Some might be corrupt, certainly—but not all. My vision was of a newspaper company that treated people fairly. If wrongdoing were to be found, we would expose it. If someone was doing a good job, we would write about that, too. Reporting was not to be an exercise in bringing people down for fun or political gain or slanting the story to make it more interesting. The company’s newspapers would bring down figures in society when warranted, lift up others when deserved, and generally seek to preserve and advance the good of society in Australia.

The vision I had was also of a company where people loved to come to work, where they were treated as human beings with aspirations, gifts, and goals. They would be respected, developed, and encouraged. Our role as the family behind the company was in part to see that employees were treated fairly. The company would, in a sense, be a family.

These were high stakes and high expectations indeed.

Even as young as I was at the time, I had a sense that both aspects of this vision had been lost, or at least watered down, over the years. It seemed that newspapers were more sensationalistic, less concerned with the truth than slanting news to make an ideological point. It seemed the business was not as well run as it used to be. I had begun to see an evolving image of a company where people did not always like coming to work.

I was also keenly aware that my father had stood in the gap to try to stem the tide of what were arguably poor management decisions. One such poor management decision, at least from my parents’ and my perspectives, was a series of capital-raising proposals. In the mid-1980s, management proposed a couple of schemes that sought to bring in capital while preserving family control. Initially, the company proposed to issue participating irredeemable preference shares (PIPS). These would be non-voting shares.

While the rest of the family, management, and the other directors were in favor of the company issuing PIPS, my parents were adamantly against it. They feared a corporate raider would snap up the PIPS and somehow force these non-voting shares to become voting shares and thereby gain control of the company. As it happened, the Sydney Stock Exchange (now part of the Australian Stock Exchange) ended up setting requirements on PIPS that would allow these shares to become voting shares under certain conditions. This was enough for the family, management, and board to abandon plans for issuing PIPS. In essence, the Sydney Stock Exchange confirmed my parents’ fears that PIPS could become voting shares, which raised the possibility of the family losing control of the company.

Another poor management decision was John’s Fairfax Ltd.’s response to Rupert Murdoch’s efforts to seize control of one of our chief competitors. In late 1986, Murdoch, owner of News Ltd., launched a takeover bid for the Herald and Weekly Times, one of the largest newspaper companies in Australia, controlling major papers in Melbourne, Brisbane, and Adelaide, and television stations in Melbourne and Adelaide. This would put the family business in a difficult, competitive position. John Fairfax Ltd. initially made a bid for the Herald and Weekly Times’ Brisbane newspaper, then ended up making a takeover bid for the whole of the Herald and Weekly Times. But the bid was too late, and Murdoch’s News Ltd. gained control of both.

In part a consequence of John Fairfax Ltd.’s legal action to try to stop News Ltd.’s takeover of the Herald and Weekly Times, our company gained control of the Herald and Weekly Times’ Melbourne television station, enabling John Fairfax Ltd. to add this station to its Seven Network stations in Sydney and Brisbane. However, complicating the purchase of the Melbourne television station was the proposed cross-media ownership legislation. Previously, a company could not own more than two television stations in Australia. After the purchase of the Melbourne television station, John Fairfax Ltd. would own three stations. The new proposed legislation would allow a company to have any number of television stations up to a certain percentage of the national audience. However, the proposed legislation also said that a company could not own a television station and a newspaper in the same market. Since John Fairfax Ltd. also owned a major profitable newspaper in Melbourne, there would be a problem. The net result was that the company was forced to sell the recently acquired Melbourne television station, and it did so by selling all three of its television stations. This drew criticism in the press at the time; a media company selling television stations, arguably core assets, was deemed unwise. In short, it seemed our company got the short end of the stick.

Fateful Decisions

Then, in February 1987, John Fairfax Ltd.’s stock price rose. Presumably, the market felt, with the upheaval from the Herald and Weekly Times takeover drama and the recent death of my father, the company might be in play. At the time, I felt the market must believe that even though the Fairfax family had close to 50 percent of the public shares in the company, 48.6 percent was not close enough. Corporate raiders were lurking. Given my thinking at the time that I must preserve family control of the company, I felt it important that the family have over 50 percent of the shares, not just 48.6 percent. So on behalf of my father’s shareholding, I bought 1.5 percent of the shares, taking the combined Fairfax family shares in the company to 50.1 percent. But while this effort did raise the family shareholding, it also hurt relations with other major family shareholders.

All these events—my perception that the company was being mismanaged, the botched dealing with the Herald and Weekly Times takeover, the purchase and subsequent forced sale of the Melbourne television station, and the “risky” capital-raising schemes—formed in my mind the need to do something. Who knew what other poor decisions management was going to make? Could I afford to wait and find out?

At the time, I believed the answer was no. So in late August 1987, at the age of twenty-six, I launched an AUS$2.25 billion takeover bid (the equivalent of USD$1.5 billion at the time). It was a high price to pay for the shares of the company, though given the nature of the market at the time, some commentators said the price was too low.

As it turned out, 1987 was one of the toughest years of my life and the turning point. It was the key crucible moment. My life would never be the same. Before 1987, I was on a path to one day having the largest shareholding in the company and being chairman and possibly chief executive. After 1987, that all changed.

In hindsight, once I launched the takeover, success was going to be elusive, if not impossible. One of the key assumptions I made was that the rest of the family would not sell after I moved to consolidate family control. I felt I needed to be in charge of what, in a sense, would be a privatized company in order to change management and ensure the business was run along the ideals of the founder. However, this meant that for the other major family shareholdings to stay in, they would have to remain shareholders in a private company without any ready ability to get out and with a twenty-six-year-old (me) in charge. What rational person would want to do this? Who would agree to be in a minority position in an essentially privatized company?

After the other two family shareholdings realized the position they were in, they decided to sell. I was told the terms of the takeover bid were such that I had to accept all offers at the price offered, including from these other major family shareholdings. I did not want them to sell, but they did. This added a huge amount to the debt load.

The other major event that hurt the company was the October 1987 stock market crash. We had planned to finance part of the takeover through selling some assets, which became even more necessary after the other major family shareholdings decided to sell. The stock market crash depressed the prices we were able to obtain for these assets.

By the end of 1987, the takeover had succeeded in the sense that I was in control of the company and was able to change management. I brought in a new chief executive, Peter King, who, in his first year, increased operating profits by 80 percent. This seemed to justify my belief that the company had not been managed as well as it could have been. However, by late 1987, the debt load was crushing. For a while, we limped along, fueled in part by the considerable increase in operating profits. We tried numerous refinancing options, even issuing bonds (so-called junk bonds) through Drexel Burnham Lambert. In the 1980s, when a company had a lot of debt and needed creative financing, Drexel was the one to turn to. However, by late 1990, Australia had gone into a recession. Traditionally, newspaper revenues were cyclical with advertising revenues, and in particular, classified advertising revenues (made up of text ads for jobs, cars, houses, and so on) being extremely cyclical. When the economy went down so did newspaper reve...