![]()

1

Baths and bathing in Rome and the Roman East

Bathing tradition was an inherent part of Roman culture. The bathhouses and the practice of visiting them were a standard component of life throughout the Roman Empire. Every city of the Empire had at least one public bathhouse, and for most city dwellers, a visit to the bathhouse was part of their daily routine.

The vital place bathhouses held in the Roman culture is easily discerned through archaeological remains. Archaeologists have excavated countless numbers of bathhouses in cities, towns, military camps, villae, and road stations in all the provinces of the Roman Empire. Bathhouses are found more commonly than any other typically Roman buildings, such as basilicae or amphitheatres. Pompeii is a case in point: it shows nine bathing establishments open to the public, which is a substantial number for a rather small town at a time not long after the bathhouses evolved into their final form (DeLaine 1988, 11–2; Zanker 2000, 39; Koloski-Ostrow 2008, 224; Yegül 2010, 2–3).

Ancient literary sources provide additional evidence. Although none dedicate themselves specifically to baths, many literary sources mention bathhouses as components of the urban landscape and a setting of social activity (Fagan 1999a, 75). The fact that ancient authors did not think it necessary to explain anything about the importance of bathing shows how ordinary and deeply rooted the routine was for them. Why describe in detail something that your readers already know about? In fact, schoolbooks used by Roman children provide the most straightforward evidence for the quotidian importance of bathing (Dionisotti 1982, 93; Fagan 1999a, 12). The schoolbooks contain two text versions, one in Latin and one in Greek, that students copied to learn how to read and write the other language. The text was a simple description of a typical day familiar to all students. All fully known schoolbooks contained a chapter devoted to visiting a bathhouse, the same as other chapters that described getting up in the morning and dining.

1.1. Origins of baths in the Roman world

Origins of the traditional Roman bathhouse is a subject debated extensively. The only point that most agree on is that the Roman bathing tradition finds itself rooted in the Greek bathing culture that preceded it (Nielsen 1990, 6; Yegül 1992, 48–50; Fagan 2001, 414; Yegül 2010, 41).

In Greek society, bathing took two forms, both of which were present in Greece itself as well as in Magna Graecia. It was probably in the colonies of Magna Graecia that the Romans first encountered Greek bathing facilities. The first type of bathing in Greek culture was washing after exercise in the gymnasium. The second was washing in private or in public using hip-bathtubs (Farrington 1999, 57; Yegül 2010, 41–5; Trümper 2013, 2).

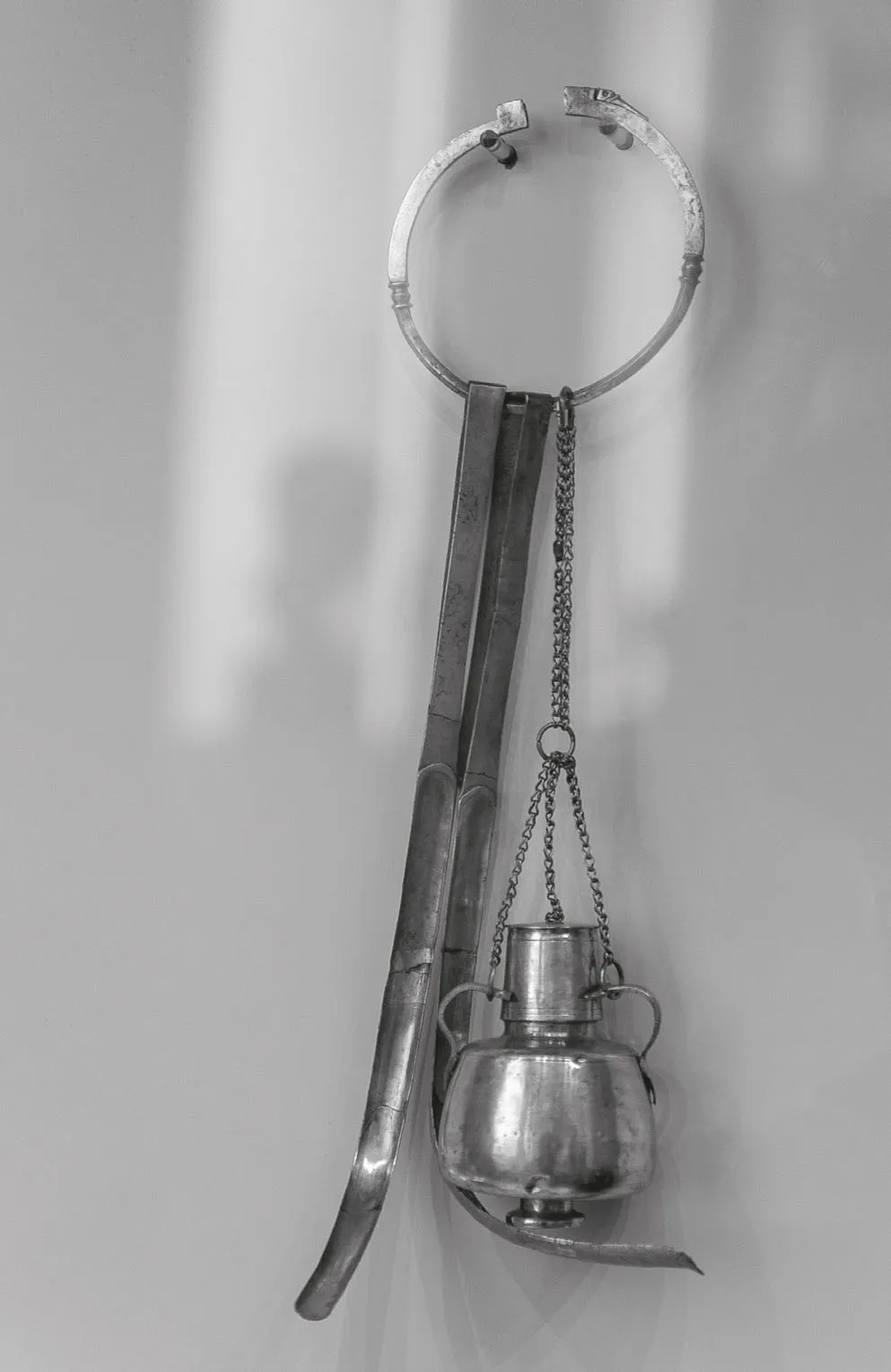

Washing in the gymnasium was done in a dedicated hall called a loutron (Fig. 1.1), equipped with simple basins and pools for cold water, delivered manually or through spouts. The athletes stood under the water stream from a spout or applied the water on their bodies by hand. The washing routine included scraping the skin with a strigilis (flattened half-moon-shaped piece of metal; Fig. 1.2; Pl. 1.1) to remove accumulated substances off the skin (dirt, sweat, and oils applied on the skin before exercise).

Hip-bathtubs for private use were present only in wealthier houses. Others could rely on public bathhouses. The Greek public bathhouse, balaneion, was a free-standing structure that often took the form of a tholos. Its main feature was multiple individual hip-bathtubs filled with warm water, which each bather poured over his head manually. Balanei were public establishments, but without additional evidence it is impossible to say by whom and how often they were frequented. The architectural remains of Hellenistic balanei demonstrate the first experiments with floor and wall heating, mainly in the form of floor channels and doubled walls. Some consider these innovations as precursors to the Roman heating system, but scholars have found no clear connection between the two (Fagan 2001; Hoss 2005, 27–9; Fournet and Redon 2013).

The Greek bathing facilities changed significantly to transform into the Roman-style bathhouse. Different influences are assumed as the source of this transformation. The strongest hypothesis, devised by Italian scholars, connects the emergence of a Roman bathhouse to heated rooms for sweating found in the central Italian countryside. Sweating was considered to have medicinal properties, such as for curing colds or relieving rheumatic pains. Greeks, however, had no sweating halls in their bathing establishments. Over time, Romans connected the sweating halls like those known from farmhouses to public bathing facilities (Yegül 2010, 45–6). Another hypothesis gives attention to natural thermal waters and heated gases harnessed for bathing purposes. Using these natural resources for bathing was popular already in the Early Republican times. Eventually, Romans developed technology to recreate the natural phenomenon in places deprived of it, so that all could enjoy bathing in hot water in heated spaces (Fagan 2001, 421; Yegül 2010, 49). Whatever the case, scholars generally agree that Campania was the region where the Roman bathhouse first emerged (Fagan 2001, 421–3; Yegül 2010, 51–8). It is in Campania that Roman settlements coexisted with Greek colonies, the ground abounds with geothermal waters and gases from the volcanic activity, and archaeologists have discovered remains of the oldest known fully-fledged Roman bathhouses (dated to the 2nd century BCE).

Fig. 1.1. Hellenistic washing hall in the Panhellenic sanctuary in Nemea. Note the basins on the sides and a shallow pool in the middle of the hall (photo. M. Eisenberg).

1.2. Specifications of bathing the Roman way

When the Roman bathhouse reached its classic form, it became a circuit of bathing halls with changing temperatures that included space for sweating, relaxation in warm water, application of oils, and plunging into cold water (Nielsen 1990, 6; Yegül 1992, 33–40; 2010, 12–8; Fagan 1999a, 10–1). A Roman bathhouse stood as a building or was a suite within a larger structure. It had at least one hall heated by means of a hypocaustum and an adjacent unheated space, both or only one of them with water facilities. Most bathhouses exceeded these minimum requirements and included a variety of other spaces.

Three halls constituted a typical Roman bathhouse: tepidarium, caldarium, and frigidarium. The tepidarium, the tepid hall, enabled acclimatization to the heat and provided space for activities, such as cleaning with oils and strigiles (as known from the Greek culture). The caldarium, the hot hall, was the core of the bathhouse, where one experienced healthy heat (estimated between 35 and 50 °C). A bather spent part of the time sitting in an alveus, a warm water pool. A water basin in the caldarium, called the labrum, provided bathers with cold water for refreshing splash. The final hall, the frigidarium, was the cold hall. A visit to a bathhouse usually ended here, with immersion in a piscina, a pool filled with cold water. Romans considered a cold finish to a bath as healthy, reinvigorating the body, and necessary to close skin pores that had opened in the heat (an observation confirmed by modern science, known to the Romans only from practice).

Fig. 1.2. Two strigiles and an oil flask on a ring carrier, exhibited in Altes Museum, Berlin (photo. M. Eisenberg).

A typical Roman bathhouse had a series of spaces that accompanied the three main halls. The apodyterium was the changing room, where one would leave their street clothes and belongings. As known from literary sources and artistic representations, the Romans entered the bathing halls from the apodyterium naked or wearing a towel, tunic, or a bikini, sometimes putting on clogs or a kind of flip-flops to separate their feet from a dirty or hot floor. They might have carried a strigilis, containers for oils, and other small cosmetic instruments (Nielsen 1990, 140–4; Yegül 1992, 33–4; Hoss 2005, 22–3). Studies of small artifacts found in bathing halls and bathhouse drains show that many other objects made their way into the bathing halls, including coins, jewellery, and even cloth-working equipment (Whitmore 2013, 279–80).

The palaestra was a court that provided space for physical exercise. Romans considered athletic activities that raised a sweat as a healthy introduction to the bathing process. This belief was a remnant of the Greek gymnasium culture. Porticoes, which surrounded the open court, were used for non-physical activities, such as gaming and gambling. In some cases, the palaestra included a natatio, a big pool for recreational swimming. Some other open or closed spaces for exercise are known from literary sources, e.g. the sphairisterion – a hall used for games involving ball (Nielsen 1990, 163–5; Yegül 2010, 14–7).

A Roman bather might have found several other halls in a bathhouse as well, but their presence was not required (Nielsen 1990, 158–61). Since Romans considered sweating as beneficial for health, and some preferred to do it in a temperature even higher than in the caldarium, some bathhouses incorporated optional heated halls for sweating. These halls were a sudatorium (wet sweat hall) and a laconicum (dry sweat hall). Halls for cosmetic and medical procedures, heated or unheated, find various names in the literary sources. The two common names are unctorium (from Latin ‘ungo’ – to anoint) and destricarium (from Latin ‘destringo’ – to rub off).

Although a visit to a bathhouse was a practice for all Romans, the particularities of the visit were a subject of choice. Among the few surviving versions of Roman schoolbooks, the text gives attention to different details of a bathhouse visit. The visit always takes place in the afternoon, after work and before dinner, and includes a passage through the hot and the cold halls, but all else seems to be open to interpretation. One bathed as one wished, choosing among what a bathing establishment offered, and often choosing between the bathhouses as well. Current fashions and latest medical trends influenced these choices, but most were probably determined by each bather’s personal preferences (Yegül 2010, 18).

Roman bathhouses differed significantly in size and lavishness, which influenced the terminology used by the Romans to describe them. The two most common terms known from literary sources are ‘thermae’ and ‘balnea.’ None of the ancient authors explains these terms precisely, but modern scholars speculate that ‘balnea’ was a term for smaller and simpler establishments, and the name ‘thermae’ concerned larger and fancier complexes (Nielsen 1990, 3; Yegül 1992, 43; Fagan 1999a, 14–9; Maréchal 2015).

A visit to balnea or thermae was an activity available to all. Literary sources often mention women in the bathhouse. In some establishments, there is a separate wing interpreted as the women’s bath; in others, the inscriptions indicate that the bathhouse was open for women at a different time than for men (Ward 1992; Yegül 2010, 33–4). It is harder to prove bathing opportunities for slaves, but several pieces of evidence suggest they were not entirely excluded (Fagan 1999b; Yegül 2010, 36). The gift of free bathing was one type of public donation, making it possible even for the poorest to enjoy the experience of a bathhouse visit (Yegül 1992, 32; Fagan 1999a, 189–219; Hoss 2005, 18, 23–4; Yegül 2010, 35).

Modern scholars sometimes classify Roman bathhouses by their clientele, which clearly shows how ubiquitous the routine was for different parts of society. The public bathhouses were open for all, though there might have been some restrictions (such as price, or membership in a club). The ownership did not play a role; a public bathhouse might have been owned privately, or be the property of the state or the emperor, or leased to a tenant, or operated by the actual owner of the building. The private bathhouses were parts of homes and villas, used only by the family and their guests (and possibly their servants/slaves as well). Another type, the military bathhouses, were establishments connected to camps and forts, constructed next to the water source or the fort settlement. The military bathhouses were built for soldiers and primarily used by them. Somewhat like military bathhouses were the monastic bathhouses, built in, or close to, monasteries. Unlike the case of military bathhouses and soldiers, it is unknown to what extent the monks used them. The baths located within sanctuaries were like public bathhouses but used by a narrower clientele consisting mainly of worshippers and other travellers who visited the sacred compound (Fagan 1999a, 5–6; Wilkes 1999, 18–9; Hoss 2005, 97).

1.3. Architecture and design of a Roman bathhouse

No matter the size, bathhouses had a particular construction style, which distinguishes them among other structures and makes them easily recognizable in the archaeological record. The ubiquitous bathhouse construction included two elements: the hypocaustum, and the water installations.

The hypocaustum was a heating system, used in Roman bathhouses and rarely also in other spaces.1 The idea was to provide a hollow space under the floor and behind the walls, in which hot air could circulate, consequently heating the bathing halls (Fig. 1.3). Vitruvius (De Architectura V.X.2) described the standard construction as follows: first, flat ground is covered with tiles one-and-a-half-foot square (sesquipedales), on this surface pillars made of eight-inch bricks (bessales) are raised to the height of two feet; finally, the pillars are covered with two-foot tiles (bipedales) that support the floor. In practice, the hypocaustum construction details differ from bathhouse to bathhouse, but always consists of a lower floor, a series of small pillars (pilae), and an upper floor (suspensura). For more effective heating, the hollow of the floor usually continued in the walls and sometimes also in the vaults by creation of cavities behind the wall facing. Builders achieved this using various prefabricated clay building products. Tegulae mammate, tiles with protruding corners (‘nipples’), or spacers, were stuck onto the wall before its final covering, but more commonly hollow ‘bricks’, known as tubuli, were used. The hypocaustum was heated from a service hall called a praefurnium. It included space for storing fuel (most often wood) and stoking, and a furnace in which combustion occurred (Nielsen 1990, 14–6; Schiebold 2010; Yegül 2010, 80–90).

Most bathhouses had water supplied off an aqueduct and had their drainage connected to the settlement’s main system. The bathhouse’s water installations consisted mainly of the pools for warm (alvei) and cold bathing (piscinae or natationes), but often they included several fountains and basins (Fig. 1.4). A piscina was usually constructed below the floor level of the frigidarium, with steps for easy descent and ascent. It had a draining hole open to a channel, and often a decorative water inlet. An alveus, on the other hand, was entirely, or almost entirely, built atop the hypocaustum in the caldarium, and took the form of steps raised above the floor of the hall to a height suitable for seated immersion. The water was heated using a boiler, located over the furnace of the hypocaustum for efficiency, or with a testudo alvei (Fig. 1.3). The testudo was a unique solution employed in Roman bathhouses. It consisted of a bronze piece shaped like half a barrel, installed over the furnace inside the wall, closed off on one side, and open to the alveus on the other, enabling a free flow of the water that heated up on the metal. Due to the need of placing testudo and boilers abov...