![]()

PART ONE

EXPLORATIONS

IN TECHNIQUES

AND MATERIALS

![]()

1 LOG STRUCTURES

IT MAY SEEM REMARKABLE that in wooded America log houses were not built and used by the earliest settlers from across the Atlantic. The only precedent for log construction which the English brought was the stake fence. In the Massachusetts Bay Colony, the Pilgrims replaced their temporary wigwams with half-timber shelters. In Virginia, before the middle of the seventeenth century, buildings both of half-timber and brick were erected, and the latter material was given increasing preference. Horizontal log construction was introduced to the New World by the Swedes, who settled along the Delaware River in 1638.1 As in Swedish peasant dwellings, rooms usually were square and had a fireplace in the corner. About 1710, German settlers in Pennsylvania began constructing log buildings, but it is not clear whether they acquired the practice from the Swedes or brought it with them from the northern Alps. Both groups initially built houses of round tree trunks, and later they squared the timbers and made neatly fitted joints. The Scotch-Irish were the first English-speaking immigrants to adopt the log cabin, and its use spread throughout the seaboard frontier. Wood being a good thermal insulator, the log house was cool in summer and by use of the fireplace could be heated in winter. The English were fully aware of the advantages of log construction by the time settlers began moving westward.

The earliest record of a log building in what would become Kentucky is in Dr. Thomas Walker’s journal for 23 April 1750. Walker, a surveyor for the Loyal Land Company of Virginia, had entered the inland territory through a cleft in the mountains he later was to name Cumberland Gap. He divided his party into two groups, directing one to remain and establish a post while he led the other into the wilderness. Upon his return, Walker recorded: “The People I left had built an House 12 by 8, clear’d and broke up some ground, & planted Corn, and Peach Stones.” This log house was four miles below Barbourville in Knox County. The site was later determined by J. Stoddard Johnston from landmarks recorded by Walker and “a pile of chimney debris.”2 A twentieth-century reconstruction includes a chimney, although Walker’s description does not mention one, and it is very unlikely that one existed until much later. Photographs taken over the years indicate that the cabin has been rebuilt several times and the chimney has changed ends.

During the middle of the eighteenth century, a more temporary type of shelter was usually fashioned by hunters, trappers, fur traders, and surveyors. Victor Collot, a French military surveyor, later called them “Forest Men.” He reported that they devised a “hut covered with the bark of trees, and supported by two poles; [with] a large fire place on the side of the opening; [and they carried] a great blanket, in which they wrap themselves up when they sleep, placing their feet towards the fire and their head in the cabin.”3 Constructing these huts required only the use of an ax, which like the blanket, they brought with them.

Joseph Doddridge termed this crude lean-to a “hunting camp” or “half-faced cabin” and described it in detail.4

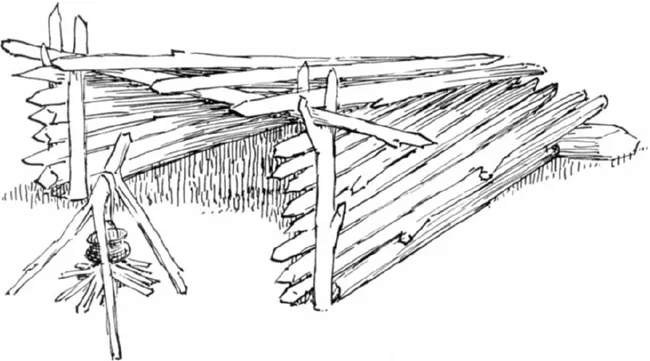

The back part of it was sometimes a large log; at the distance of eight or ten feet from this two stakes were set in the ground a few inches apart, and at the distance of eight or ten feet from these two more, to receive the ends of the poles for the sides of the camp. The whole slope of the roof was from the front to the back. The covering was made of slabs, skin and blankets, or, if in the spring of the year, the bark of hickory or ash trees. The front was left entirely open. The fire was built directly before this opening. The cracks between the logs were filled with moss. Dry leaves served for a bed. It is thus that a couple of men, in a few hours, will construct for themselves a temporary, but tolerably comfortable, defense from the inclemencies of the weather [fig. 1.1]. . . . A cabin ten feet square, bullet proof and furnished with port holes, would have enabled two or three hunters to hold twenty Indians at bay for any length of time. But this precaution I believe was never attended to; hence the hunters were often surprised and killed in their camps.

Fig. 1.1 Sketch of a half-faced cabin.

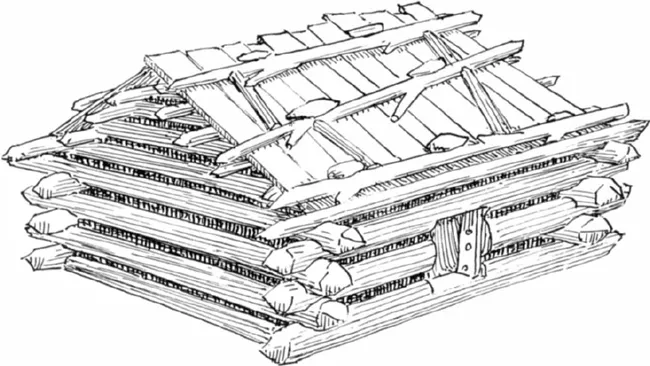

Early settlers who came to stay devised the “improvement” cabin, so designated because it was not only better built than the half-faced but also a symbol of a man’s right to land occupancy, being part of the improvement he made to his property. This type was built like the Walker cabin, of felled trees, stripped of their branches, and the logs notched at the ends to fit into one another. Thus was raised a square pen, with an entrance hole in one wall and covered by a sloping roof. The walls were only a few timbers in height, as logs were upward of a foot in diameter, and the open spaces between them were half that. The roof was covered with clapboards (fig. 1.2). One could stand upright only in the middle of the pen. Improvement cabins were virtually bunkhouses; cooking was done outside.

Fig. 1.2 Sketch of an improvement cabin.

The first improvement cabins were built at the site of Harrodsburg by James Harrod and his party of some thirty Pennsylvanians, who camped on the south side of Big Spring Branch early in 1774. They planned a town, planted corn, and surveyed for land claims. Attacked by Indians and suffering a casualty, they went back home. Harrod returned with more allies the following spring, and they reoccupied the improvement cabins. James Norse, head of a company taking up lands in Kentucky, visited the little community on 5 June 1775. He described “Hardwoodtown” as consisting of “about 8 or 10 log cabins without doors nor stopped” (chinked).5 At this time Harrod was at his preemption, Boiling Springs, about six miles away, and Norse called on him en route to “Boonesburg.” He recorded that Harrod had “a tolerable good house having a floor and a Chimney but not stopt.”6 The split-puncheon floor and fireplace were features incorporated in cabins to be built in Fort Harrod.

Examples of the earliest structures of round logs are now rare because of the natural deterioration of wood and an aversion later generations had for rusticity. A domestic survivor is an eighteen-foot-square addition to a shaped-log house about five miles west of Harrodsburg on the Johnson Road. It is remarkable that the primitive addition is later than the more sophisticated core. Logs of both parts are saddle-notched at the corners. Ends of the round logs adjoining the older cabin are hewn into vertical tenons, which have been inserted between double puncheons pinned into the corners of the original pavilion (fig. 1.3). A door and window were in each of the front and rear walls, and a chimney was centered on the outer flank. The building has almost a full second story. In the old section, upper-floor joists rest on horizontal strips of wood pegged to the walls like the puncheons for the addition, perhaps indicating a contemporary improvement.

Fig. 1.3 Junction of a round-log pen with an older square-log cabin on Johnson Road, Mercer County. Photo, 1982.

A number of round-log dependencies are extant in Kentucky. In Mercer County, between the Johnson Road cabin and Central Pike, stands a well-preserved barn that serves as a mow in an enlarged barn, which has protected it from the weather for many years. A corncrib of slender round logs is on the nearby Turner Bottom tract on Chaplain River, near Bruners Chapel Road. Two examples in Woodford County accompany the General Scott House on Soard Ferry Road and the Joel DuPuy House on Grier’s Creek (fig. 1.4). These outbuildings are probably several decades later than the earliest dwellings.

Shortly after the settlers from Pennsylvania returned to their improvement cabins on Big Spring Branch in 1775, downstream from the settlement they erected a fort named for their leader.

FORT HARROD. Its northern palisade ran parallel to a stretch of the stream, which flowed directly from east to west, and about sixteen feet distant. One of its two gateways was centered in this side. Fortunately, a detailed description of this first permanent settlement in Kentucky was made in 1791 by Benjamin Van Cleve, a young man with “a strong penchant for visiting and mapping old forts.” Although the fort had been changed and enlarged, Van Cleve recorded from interviews with older inhabitants how it had been built originally.7

Fig. 1.4 Corner detail of log outbuilding at the Joel DuPuy House, Woodford County. Photo, 1964.

[It is]a square of 264 feet [fig. 1.5]. The S.W. and S.E. corners are block houses about 25 by 44 feet each. In the N.W. corner is a spring and on the eastern side is another spring. The south line of the fort or the hill is a solid row of log cabins. . . . The east, north and west sides are stockades. Gates of stout timber ten feet wide open on the west and on the north sides . . . defended by port holes, the doors are secured by heavy bars.

The pickets are round logs of oak, grown near by, and all of them more than a foot in diameter. They are set four feet in the ground leaving ten feet clear and the earth rammed tight. They are held together with stout wall pieces pinned in through holes with inch tree nails on the side.

The corner buildings are blockhouses, the upper stories extend two feet from the walls on each side providing for gunfire along the walls.

Seven . . . cabins are between the [two south] block houses. . . . The cabins are 20 by 20, with a space of ten feet between them. They are built of round logs, a foot in diameter, chinked and pointed with clay in which straw has been mixed as a binder. The doors and the window shutters are of oaken puncheons, secured by stout bars on the inside with the latch-string of leather hanging out.

The buildings are a story-and-a-half structures the slope of the roof being entirely to the inside. In the attic of each cabin is a puncheon of water, always filled, and to be used in case of fire. The Indians, on several occasions succeeded in firing the roofs with burning arrows and these casks of water was all that saved them.

The eave bearers are the end logs which project over to receve the butting poles, against which the lower tier of clapboards rest in forming the roof. The trapping is the roof timbers composing the gable ends and the ribs upon which the course of clapboards lie. The weight poles are those small logs on the roof which weigh down the clapboards upon which they lie and against which the next course is laid. The knees are pieces of heart timber laid above the butting poles to prevent the poles rolling off [fig. 1.6].

A ladder of five rounds occupies the corner near the window and the walls are hung with articles of clothing that give some seclusion. Floor boards are hewn with ax [a...