eBook - ePub

Omega - The Last days of the World

With the Introductory Essay 'Distances of the Stars'

- 236 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Omega - The Last days of the World

With the Introductory Essay 'Distances of the Stars'

About this book

In the twenty-fifth century AD, a comet will collide with the earth and bring about the end of the world. Faced with this apocalyptic knowledge, humanity undergoes a multitude of social, physical and psychic changes that engender incredible alterations to both people and planet over many millennia. Beautifully illustrated, this novel is a fascinating vision of humanity millions of years in the future. Camille Flammarion's 1893 science fiction novel "Omega" marries reasonable scientific speculation and philosophy in this impressive exploration of things that may be to come. Nicolas Camille Flammarion FRAS (1842–1925) was a French author and astronomer. A prolific writer, he produced over fifty books including science fiction novels, works on astronomy, and works on physical research. Other titles by this author include: "The Plurality of Inhabited Worlds" (1862), "Real and Imaginary Worlds" (1865), and "God in Nature" (1866). Read & Co. Classics is proudly republishing this vintage science fiction novel now in a new edition complete with the introductory essay 'Distances of the Stars'.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Omega - The Last days of the World by Camille Flammarion in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Science Fiction. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

FIRST PART

CHAPTER I

The magnificent marble bridge which unites the Rue de Rennes with the Rue de Louvre, and which, lined with the statues of celebrated scientists and philosophers, emphasizes the monumental avenue leading to the new portico of the Institute, was absolutely black with people. A heaving crowd surged, rather than walked, along the quays, flowing out from every street and pressing forward toward the portico, long before invaded by a tumultuous throng. Never, in that barbarous age preceding the constitution of the United States of Europe, when might was greater than right, when military despotism ruled the world and foolish humanity quivered in the relentless grasp of war—never before in the stormy period of a great revolution, or in those feverish days which accompanied a declaration of war, had the approaches of the house of the people’s representatives, or the Place de la Concorde presented such a spectacle. It was no longer the case of a band of fanatics rallied about a flag, marching to some conquest of the sword, and followed by a throng of the curious and the idle, eager to see what would happen; but of the entire population, anxious, agitated, terrified, composed of every class of society without distinction, hanging upon the decision of an oracle, waiting feverishly the result of the calculations which a celebrated astronomer was to announce that very Monday, at three o’clock, in the session of the Academy of Sciences. Amid the flux of politics and society the Institute survived, maintaining still in Europe its supremacy in science, literature and art. The center of civilization, however, had moved westward, and the focus of progress shone on the shores of Lake Michigan, in North America.

CHAPTER II

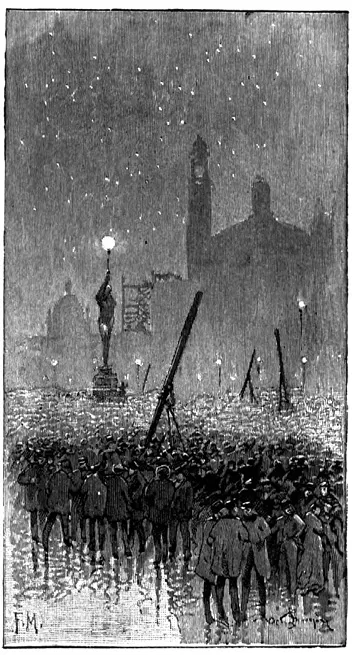

The stranger had emerged slowly from the depths of space. Instead of appearing suddenly, as more than once the great comets have been observed to do,—either because coming into view immediately after their perihelion passage, or after a long series of storms or moonlight nights has prevented the search of the sky by the comet-seekers—this floating star-mist had at first remained in regions visible only to the telescope, and had been watched only by astronomers. For several days after its discovery, none but the most powerful equatorials of the observatories could detect its presence. But the well-informed were not slow to examine it for themselves. Every modern house was crowded with a terrace, partly for the purpose of facilitating aerial embarkations. Many of them were provided with revolving domes. Few well-to-do families were without a telescope, and no home was complete without a library, well furnished with scientific books.

The comet had been observed by everybody, so to speak, from the instant it became visible to instruments of moderate power. As for the laboring classes, whose leisure moments were always provided for, the telescopes set up in the public squares had been surrounded by impatient crowds from the first moment of visibility, and every evening the receipts of these astronomers of the open air had been incredible and without precedent.

Many workmen, too, had their own instruments, especially in the provinces, and justice, as well as truth, compels us to acknowledge that the first discoverer of the comet (outside of the professional observers) had not been a man of the world, a person of importance, or an academician, but a plain workman of the town of Soissons, who passed the greater portion of his nights under the stars, and who had succeeded in purchasing out of his laboriously accumulated savings an excellent little telescope with which he was in the habit of studying the wonders of the sky. And it is a notable fact that prior to the twenty-fourth century, nearly all the inhabitants of the earth had lived without knowing where they were, without even feeling the curiosity to ask, like blind men, with no other preoccupation than the satisfaction of their appetites; but within a hundred years the human race had begun to observe and reason upon the universe about them

The Street Telescopes

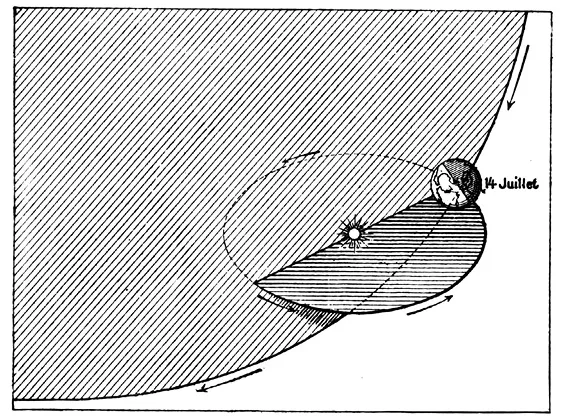

To understand the path of the comet through space, it will be sufficient to examine carefully the accompanying chart. It represents the comet coming from infinite space obliquely towards the earth, and afterwards falling into the sun which does not arrest it in its passage toward perihelion. No account has been taken of the perturbation caused by the earth’s attraction, whose effect would be to bring the comet nearer to the earth’s orbit. All the comets which gravitate about the sun—and they are numerous—describe similar elongated orbits,—ellipses, one of whose foci is occupied by the solar star. The drawing on page 39 gives an idea of the intersections of the cometary and planetary orbits, and the orbit of the earth about the sun. On studying these intersections, we perceive that a collision is neither an impossible nor an abnormal event.

The comet was now visible to the naked eye. On the night of the new moon, the atmosphere being perfectly clear, it had been detected by a few keen eyes without the aid of a glass, not far from the zenith near the edge of the milky way to the south of the star Omicron in the constellation of Andromeda, as a pale nebulæ, like a puff of very light smoke, quite small, almost round, slightly elongated in a direction opposed to that of the sun—a gaseous elongation, outlining a rudimentary tail. This, indeed, had been its appearance since its first discovery by the telescope. From its inoffensive aspect no one could have suspected the tragic role which this new star was to play in the history of humanity. Analysis alone indicated its march toward the earth.

But the mysterious star approached rapidly. The very next day the half of those who searched for it had detected it, and the following day only the near-sighted, with eyeglasses of insufficient power, had failed to make it out. In less than a week every one had seen it. In all the public squares, in every city, in every village, groups were to be seen watching it, or showing it to others.

The Comet as Seen at Paris

Day by day it increased in size. The telescope began to distinguish distinctly a luminous nucleus. The excitement increased at the same time, invading every mind. When, after the first quarter and during the full moon, it appeared to remain stationary and even to lose something of its brilliancy, as it had been expected to grow rapidly larger, it was hoped that some error had crept into the computations, and a period of tranquillity and relief followed. After the full moon the barometer fell rapidly. A violent storm-center, coming from the Atlantic, passed north of the British Isles. For twelve days the sky was entirely obscured over nearly the whole of Europe.

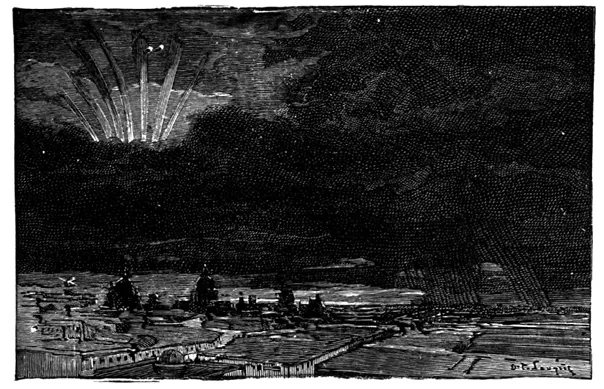

Once more the sun shone in purified atmosphere, the clouds dissolved and the blue sky reappeared pure and unobscured; it was not without emotion that men waited for the setting of the sun—especially as several aerial expeditions had succeeded in rising above the cloud-belts, and aeronauts had asserted that the comet was visibly larger. Telephone messages sent out from the mountains of Asia and America announced also its rapid approach. But great was the surprise when at nightfall every eye was turned heavenward to seek the flaming star. It was no longer a comet, a classic comet such as one had seen before, but an aurora borealis of a new kind, a gigantic celestial fan, with seven branches, shooting into space seven greenish streamers, which appeared to issue from a point hidden below the horizon.

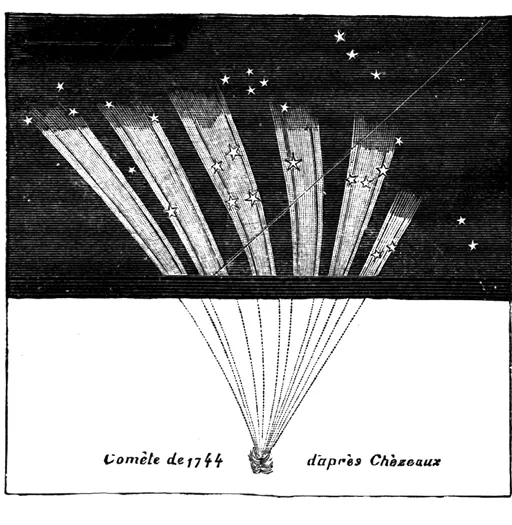

No one had the slightest doubt but that this fantastical aurora borealis was the comet itself, a view confirmed by the fact that the former comet could not be found anywhere among the starry host. The apparition differed, it is true, from all popularly known cometary forms, and the radiating beams of the mysterious visitor were, of all forms, the least expected. But these gaseous bodies are so remarkable, so capricious, so various, that everything is possible. Moreover, it was not the first time that a comet had presented such an aspect. Astronomy contained among its records that of an immense comet observed in 1744, which at that time had been the subject of much discussion, and whose picturesque delineation, made de visu by the astronomer Chèzeaux, at Lausanne, had given it a wide celebrity.

But even if nothing of this nature had been seen before, the evidence of one’s eyes was indubitable.

Meanwhile, discussions multiplied, and a veritable astronomical tournament was commenced in the scientific reviews of the entire world—the only journals which inspired any confidence amid the epidemic of buying and selling which had for so long a time possessed humanity. The main question, now that there was no longer any doubt that the star was moving straight toward the earth, was its position from day to day, a question depending upon its velocity. The young computor of the Paris observatory, chief of the section of comets, sent every day a note to the official journal of the United States of Europe.

A very simple mathematical relation exists between the velocity of every comet and its distance from the sun. Knowing the former one can at once find the latter. In fact the velocity of the comet is ...

Table of contents

- DISTANCES OF THE STARS

- FIRST PART

- SECOND PART