- 180 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Media, Development and Democracy

About this book

Sponsored by the Communication, Information Technologies, and Media Sociology section of the American Sociological Association (CITAMS), this book explores the complex construction of democratic public dialogue in developing countries. Case studies examine national environments defined not only by state censorship and commercial pressure, but also language differences, international influence, social divisions, and distinct value systems.

With fresh portraits of new and traditional media throughout Africa, Latin America and Asia, authors delve into the essential role of the media in developing countries. Case studies illuminate the relationship between the State and the media in Russia, as well as the challenges faced by journalists working in Kurdistan. Further cases reveal bureaucratic censorship of books in Brazil, regulatory dilemmas in Australia, state policies in post-colonial Malawi, and the potential of oral culture for the strengthening of democratic conversation.

Media, Development and Democracy brings the liberal democratic media model into new terrains where some of its core assumptions do not hold. In doing so, the authors' collective voices illuminate pressing issues facing our current global dialogue and our liberal and democratic expectations concerning communications and the media. This essential volume works as a magnifying glass for our current times, forcing us to question what kind of media we want today

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CHAPTER 1

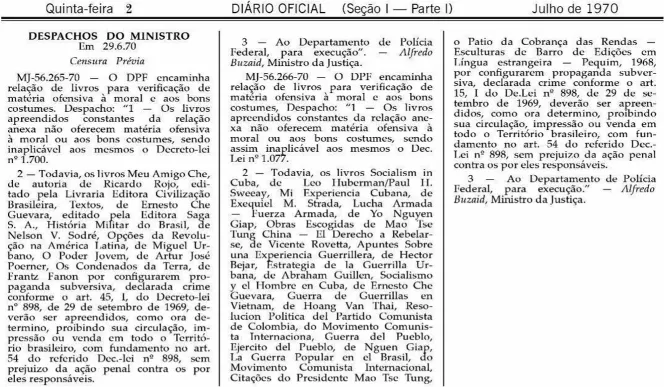

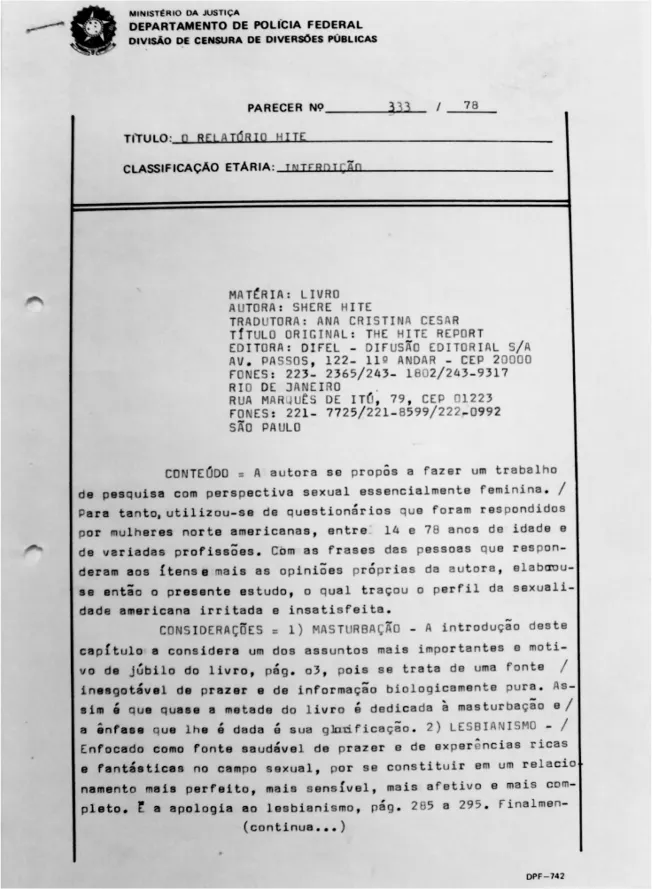

FOREIGN AUTHORS, NATIONAL BANS: BOOKS AND CENSORSHIP IN BRAZIL (1964–1985)

ABSTRACT

REASONS FOR CENSORSHIP: BOOK CENSORSHIP AND CENSORIAL REGULATIONS

NON-FICTION WORKS BY FOREIGN AUTHORS PUBLISHED AND THEN CENSORED IN BRAZIL

- Frantz Fanon. Os Condenados da Terra [The Wretched of the Earth]. Rio de Janeiro: Civilização Brasileira, 1968. [Censorship document number: DOU 02.07.1970]

- Ricardo Rojo. Meu Amigo Che [My Friend Che]. Rio de Janeiro: Civilização Brasileira, 1968. [Censorship document number: DOU 02.07.1970]

- Che Guevara. Textos de Che Guevara [Texts]. Rio de Janeiro: Saga, 1968. [Censorship document number: DOU 02.07.1970]

- Mao Tsé-Tung. Citações do Presidente Mao Tsé-Tung [Quotations from Chairman Mao Tse-Tung]. Rio de Janeiro: José Álvaro, 1967. [Censorship document number: DOU 02.07.1970]

- Miguel Urbano (a Portuguese exile). Opções da Revolução na América Latina [Revolution Options in Latin America]. Ri...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Overlapping Communicative Meshes: Plural Perspectives on Media and Development

- Chapter 1. Foreign Authors, National Bans: Books and Censorship in Brazil (1964–1985)

- Chapter 2. Manufacturing the Liberal Media Model Through Developmentality in Malawi

- Chapter 3. Toward a Framework for Studying Democratic Media Development and “Media Capture”: The Iraqi Kurdistan Case

- Chapter 4. Regulating Unhealthy Food Advertising to Children under Neoliberalism: An Australian Perspective

- Chapter 5. How Russian Media Helped Develop the Authoritarian Tradition: Its Historical Legacy for Today

- Chapter 6. How to Capture the Political in Everyday Conversation? Focus Groups as a Method to Research Democratic Practices in Daily Life

- Index

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app