![]()

1

THE PREDICTION MACHINE

How your beliefs shape your reality

It was just a few nights before Christmas, and the drones seemed to be everywhere and nowhere at the same time.

The drama began at 9 p.m. on 19 December 2018, when a security officer at London Gatwick Airport reported two unmanned aerial vehicles – one flying around the perimeter fence, another inside the complex. The runway was soon closed for fear of an impending terrorist attack. It was only 19 months after the Islamist bombing at the Manchester Arena, after all, and there had been reports that Isis were planning to carry explosives on commercial drones.

The chaos escalated over the following 30 hours, as dozens of further sightings kept the airport in lockdown. Try as they might, however, the security officers and police just couldn’t locate the drones, which seemed to disappear as soon as they were sighted. Even more astonishingly, their operators appeared to have found a way to avoid the military’s track-and-disable system, which was unable to detect any unusual activity in the area, despite a total of 170 reported sightings. The news soon spread to the international media, who warned that similar attacks might occur in other countries.

By 6 a.m. on 21 December, the threat finally seemed to have passed, and the airport reopened for business. Whoever was behind the attack – be it a terrorist or a joker – had achieved their aim of chaos, disrupting the travels of 140,000 passengers, with the cancellation of more than a thousand flights. Despite offering a substantial reward, the police have been completely unable to find a culprit, and there is not a single photo offering evidence of an attack – leading some (including members of the police) to question whether there were ever any drones at all.1 Even if there was, at one point, a drone near the airport, it’s clear that the vast majority of the sightings were false, and the ensuing chaos was almost certainly unnecessary.

With so many independent reports from dozens of sources, we can easily rule out the possibility that this was some kind of lie or conspiracy. Instead, the event demonstrates the power of expectation to change our perception, and – occasionally – to create a vision of something that is entirely false.

According to an increasing number of neuroscientists, the brain is a ‘prediction machine’ that constructs an elaborate simulation of the world, based as much on its expectations and previous experiences as the raw data hitting the senses. For most people, most of the time, these simulations coincide with objective reality, but they can sometimes stray far from what is actually in the physical world.2

Knowledge of the prediction machine can explain everything from ghost sightings to disastrously bad calls by sports referees – and the mysterious appearance of non-existent drones in the winter sky. It can help us to understand why the brand name of a beer can change its taste, and it shows how, to someone with a phobia, the world looks much more terrifying than it really is. This grand new unifying theory of the brain also sets the stage for all the expectation effects that we’ll examine in this book.

THE ART OF SEEING

The seeds of this extraordinary conception of the brain were sown in the mid-nineteenth century by the German polymath Hermann von Helmholtz. Studying the anatomy of the eyeball, he realised the patterns of light hitting the retina would be too confusing to enable us to recognise what is around us. The 3D world – with objects at various distances and odd angles – has been flattened onto two two-dimensional discs, resulting in obscured and overlapping contours that would be difficult to interpret. And even the same object may reflect very different colours, depending on the light source. If you are reading this physical book indoors at dusk, for example, the page will be reflecting less light than a dark grey page in direct sunlight – yet in both cases, they look distinctly white.

Helmholtz suggested that the brain draws on past experiences to tidy up the visual mess and to come up with the best possible interpretation of what it receives, through a process that he called ‘unconscious inference’. We may think we are seeing the world unfiltered, but vision is really forged in the ‘dark background’ of the mind, he proposed, based on what it assumes is most likely to be in front of you.3

Helmholtz’s theories of optics influenced Post-Impressionist artists like Georges Seurat,4 but it was only in the 1990s that the idea really started to take off in neuroscience – with signs that the brain’s predictions influence every stage of visual processing.5

Before you walk into a room, your brain has already built many simulations of what might be there, which it then compares with what it actually encounters. At some points, the predictions may need retuning to better fit the data from the retina; at others, the brain’s confidence in its predictions may be so strong that it chooses to discount some signals while accentuating others. Over numerous repetitions of this process, the brain arrives at a ‘best guess’ of the scene. As Moshe Bar, a neuroscientist at Bar-Ilan University in Israel who has led much of this work, puts it: ‘We see what we predict, rather than what’s out there.’

A wealth of evidence now supports this hypothesis, right down to the brain’s anatomy. If you look at the wiring of the visual cortex at the back of the head, you find that the nerves bringing electrical signals from the retina are vastly outnumbered by the neural connections feeding in predictions from other regions of the brain.6 In terms of the data it provides, the eye is a relatively small (but admittedly essential) element of your vision, while the rest of what you see is created ‘in the dark’ within your skull.

By measuring the brain’s electrical activity, neuroscientists like Bar can watch the effects of our predictions in real time. He has observed, for instance, the passing of signals from frontal regions of the brain – which are involved in the formation of expectations – back into the visual cortex at the earliest stages of visual processing, long before the image pops into our consciousness.7

There are lots of good reasons why we might have evolved to see the world in this way. For one thing, the use of predictions to guide vision helps the brain to cut down the amount of sensory information it actually processes, so that it can focus on the most important details – the things that are most surprising, and which do not fit its current simulations.

As Helmholtz originally noted, the brain’s reliance on prediction can also help us to deal with incredible ambiguity.8 If you look at the following image – a real, albeit poor-quality, bleached photograph – you will probably struggle to identify anything recognisable.

If I tell you to look for a cow, however – facing you, with its large head towards the left of the image – you may find that something somehow ‘clicks’ and the image suddenly makes a lot more sense. If so, you’ve just experienced your brain’s predictive processing retuning its mental models to make use of additional knowledge, transforming the picture into something meaningful.

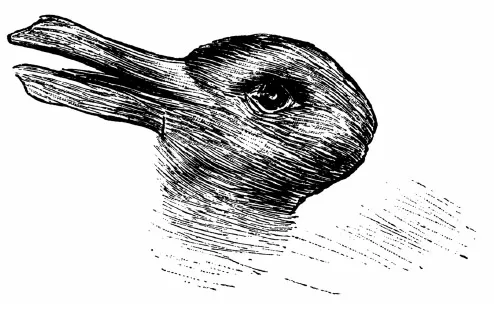

Or what do you see when you look at the following? (Try for at least 10 seconds before going on.)

If you’re like me, you will initially find it extremely hard to make out anything specific. What if I tell you it’s a popular pet? If you’re still struggling to make it out, refer to the original image (here). It should now become a lot clearer: that’s your brain’s updated predictions suddenly making sense of the mess.9 Once you’ve seen it, it’s almost impossible to believe that you were ever confused by the image – and the effect of those updated predictions is enduring. Even if you return to this page in a year’s time, you’ll be much more likely to make sense of the image than when you first saw the incomprehensible splodges of black and white.

The brain will draw on any contextual information it can to refine its predictions – with immediate consequences for what we see. (If you’d seen the picture in a pet shop or a veterinary surgeon’s office, you may have been far more likely to have seen the dog at first glance.) Even the time of year can determine how your brain processes ambiguous sights. A pair of Swiss scientists, for example, stood at the main entrance of Zürich Zoo and asked participants what they saw when looking at a version of a famously ambiguous visual illusion:

In October, around 90 per cent of the zoo visitors reported seeing a bird looking to the left. At Easter, however, that dropped to 20 per cent, while the vast majority saw it as a rabbit looking to the right. Of children under ten, for whom the Easter Bunny may be an especially important figure, nearly 100 per cent saw a rabbit on the holiday weekend. The prediction machine had weighed up which potential interpretation of the ambiguous picture was most relevant, and the season managed to tip the balance – with a tangible effect on people’s conscious visual experience.10

We now know that the ‘top down’ influence of the brain’s expectations is not limited to vision but governs all kinds of sensory perception. And it is incredibly effective. Suppose you are driving on a misty day: if you are familiar with the route, your previous experiences will help your brain to make out the sight of a road sign or another car, so that you avoid having an accident. Or imagine you are trying to work out the meaning of someone’s words on a crackly telephone line. This will be much easier if you are already familiar with the accent and cadences of the speaker’s voice, thanks to the prediction machine.

By predicting the effects of our movements, the brain can damp down the feeling of touch when one part of our body makes contact with another, so that we don’t jump out of our skin whenever one of our legs brushes against the other, or our arm touches our side. (It is also for this very reason that we can’t tickle ourselves.) Errors in people’s internal simulations might also explain why amputees still often feel pain in their missing limbs – the brain hasn’t fully updated its map of the body, and erroneously predicts that the arm or limb is in great distress.

There will inevitably be some small errors in each of the brain’s simulations of the world around us – a mistaken object or a misheard sentence that is soon corrected. Occasionally, however, those simulations can go completely awry, with heightened expectations evoking vivid illusions of things that do not exist in the real world – such as drones flying over the UK’s second biggest airport.

In one brilliant demonstration of this possibility, participants were asked to watch a screen of random grey dots (like the ‘snow’ on an untuned analogue TV). With a suitable suggestion, they could be primed to see faces in 34 per cent of trials, even though there was nothing there apart from random visual noise. The expectation that a face would appear led the brain to sharpen certain patterns of pixels in the sea of grey, leading people to hallucinate a meaningful image with astonishing frequency. What’s more, brain scans showed the brain forming these hallucinations in real time, with the participants demonstrating heightened neural activity in the regions normally associated with face perception.11 Clearly, seeing isn’t believing – believing is seeing.

Believing is also hearing. Dutch researchers told some students that they might be able to hear a very faint rendition of ‘White Christmas’ by Bing Crosby embedded in a recording of white noise. Despite the fact that, objectively, there was not a hint of music, nearly one-third of participants reported that they could really hear the song. The implanted belief about what they were about to hear led the students’ brains to process the white noise differently, accentuating some elements while muting others, until they hallucinated the sound of Crosby singing. Interestingly, a follow-up study found that auditory hallucinations of this kind are more common when we feel stressed and have consumed caffeine, which is thought to be a mildly hallucinogenic substance and may lead the brain to place more confidence in its predictions.12

If we cast our minds back to those officers at Gatwick, it’s easy to imagine how fears of an impending terrorist attack could conjure up the image of a drone in the grey blanket of the winter sky, where there might be many ambiguous figures – birds or helicopters, for example – that the prediction machine is liable to misinterpret. And the more sightings that were reported, the more people would have expected to see further drones. Had scientists been able to peer into their brains, it is likely that they would have observed exactly the same brain activity as someone looking at an actual drone.13

Momentary hallucinations of this kind can result from the prediction machine’s errors in countless other situations. Strange visions are apparently common among polar explorers, for example, as the unchanging blankness of the landscape – the ‘white darkness’, as some describe it – plays havoc with the prediction machine’s simulations.

One of the most memorable examples of this phenomenon concerns Roald Amundsen’s expedition to Antarctica. On 13 December 1911, Amundsen’s team was within spitting distance of the Pole, and dreaded the thought that Robert Falcon Scott’s competing expedition might beat them to their goal. As they made up camp, one of Amundsen’s group, Sverre Helge Hassel, called out that he had spotted people moving in the distance. Soon the whole team could see them. When the explorers ran forward, however, they soon discovered that it was simply a pile of their own dogs’ turds lying on the snow. The explorers’ minds had transformed a pile of faeces into the thing they feared.14

Many supposedly paranormal experiences may arise through a similar process. When a fire broke out at Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris on 15 April 2019, for example, a number of eyewitnesses reported seeing the form of Jesus in the flames.15 Some assumed it was a sign of God’s disapproval at the turn of events; others, that He was trying to offer comfort to those affected by the damage....