![]()

| 1 | Egyptian Afterlives in the Modern World |

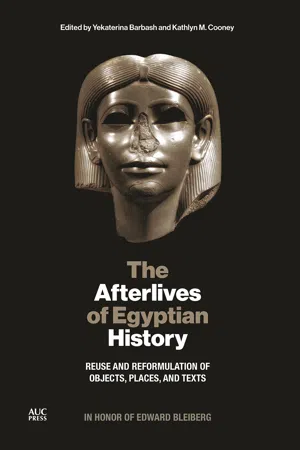

Fig. 1.1. Outer sarcophagus, coffin, and mummy board of the royal prince, count of Thebes, Pa-seba-khai-en-ipet, ca. 1075–945 BCE; wood (cedar and acacia), gesso, pigment; outer sarcophagus: 94 x 76.8 x 211.8 cm (37 x 30 1/4 x 83 3/8 in); coffin: 32 x 55 x 194 cm (12 5/8 x 21 5/8 x 76 3/8 in). Brooklyn Museum, Charles Edwin Wilbour Fund, 08.480.1a–b and 08.480.2a–c. Photograph courtesy of the Brooklyn Museum.

![]()

| 1 | Egyptian Mummies at the Brooklyn Museum: Changing Attitudes and Perceptions |

| | Lisa Bruno |

THE BROOKLYN MUSEUM HAS COLLECTED OBJECTS from ancient Egypt since the early twentieth century.1 An early acquisition of a complete human mummy was almost an unintended accident.2 In 1908, the museum acquired the private collection of Armand de Potter. This was an early private collection built during the 1880s and 1890s. Included in the collection was a spectacular Twenty-first Dynasty sarcophagus consisting of an outer coffin (08.480.1ab), an inner coffin with a mummy board (08.480.2a–c), and the mummy of a man named Pa-seba-khai-en-ipet (08.480.2d). This was most certainly the coffin of an individual of some stature and note. He held the titles of royal prince and count of Thebes. An early glass-plate negative taken to record the new acquisition shows all components of the sarcophagus ensemble except one: the mummy itself (fig. 1.1).

While the sarcophagus was celebrated as an important work of art, the mummy was not. So it began, the complicated and at times ambivalent relationship that the Brooklyn Museum, along with many institutions, has had with ancient Egyptian mummies. They are what the general public first thinks of when discussing ancient Egyptian art and yet, while beautiful and often exhibiting the great deftness and skill of ancient artists and craftsmen, the mummies are not art objects. They are the remains of human beings.

The Brooklyn Museum and the curators of the arts of Egypt, starting with Dr. John Cooney and continuing with Dr. Edward Bleiberg, set the tone for care of the collections. Like any curator responsible for a collection, they are influenced by the prevailing attitudes of the time, as well as by colleagues in allied professions such as conservators. This chapter will outline some of the early perceptions and attitudes toward human mummies as illustrated by what happened to them, and how these practices changed over time as biases shifted and perceptions widened. In looking at the historic records at the museum, the physical mummy itself was not often valued beyond its artistic merit. This attitude was commonplace among the staff of art museums established in the nineteenth century. While natural history and university museums often did have an interest in the mummified remains, the mummies were merely looked at as specimens to be examined, sampled, and autopsied.3

The Brooklyn Museum has eight human mummies and several body parts, including severed heads, hands, and feet. The oldest of the museum’s mummies is Pa-seba-khai-en-ipet (08.480.2d), with a date range of 1188–909 BCE. The most recent mummy is that of an anonymous man (52.128a–e) that dates from 244–419 CE.4 There is a rare Roman Period red-shroud mummy known as Demetrios (11.600a–b) that dates from 50–100 CE.5 A Late Period (791–418 BCE) mummy wrapped in crossed linen is named Thothirdes (37.1521Ec).6 Another male mummy (37.14Ec–e) is not a mummy at all but rather skeletal remains, due to the history of its embalmment and circumstances. There are two mummies in the collection encased in cartonnage from the Third Intermediate Period, and the last is a partial mummy (37.47E) from 993–812 BCE.7 Of the eight mummies, two were unwrapped, with one suffering damage beyond treatment at the time of this writing. Two suffered general neglect and two were subject to physical damage, while two remained undisturbed and intact.

While the mummy of Pa-seba-khai-en-ipet was accessioned at the time of acquisition by the museum in 1908, it was not fully cataloged.8 Because its status was undefined as an associated but unrecognized component of the accessioned artwork, including the coffins and mummy board, it meant that there were no procedures or protocols in place for how to care for or study this mummy. This eventually led to its unwrapping by a curatorial researcher in the 1970s. Other mummies in the collection, including Demetrios, with its realistically painted portrait mask, and the Roman Period mummy of an anonymous man, with a painted plaster portrait mask that has a three-dimensional molded crown, were both separated from their face masks. The masks were displayed without an acknowledgment of their direct relationship to death and mummification because they were displayed without the mummified humans they were made for. The mummy of Thothirdes entered the Brooklyn Museum’s collection by way of the New-York Historical Society (NYHS) from the early collection formed by Dr. Henry Abbott. Thothirdes arrived with a beautiful polychrome Late Period, Twenty-sixth Dynasty (ca. 664–525 BCE) coffin painted on both the interior and exterior. When the mummy of Thothirdes and, more importantly, his coffin, went on display in the newly constructed Egyptian galleries designed by Arata Isozaki in the early 1990s, the coffin was stabilized and treated but the mummy was not. The mummy’s linen wrappings were exhibited in slight disarray for nearly twenty years until being conserved in 2010.9

The fact that mummies were considered peripheral or incidental to the decorative and artistic objects associated with them allowed them to be subject to at least indifference and at most violation and abuse. This lack of reverence was not unique to our contemporary Western society. The ancient Egyptians themselves practiced tomb robbing and creative reuse of coffins. This reuse is perfectly evidenced by the reinscription of an early Nineteenth Dynasty coffin of the Lady of the House, Weretwahset (37.47E), in the museum’s collection.10 The coffin was reinscribed and presumably reused for the Lady of the House, Chantress of Amun, Bensuipet, in the Twentieth or Twenty-first Dynasty.11 When the coffin was examined by the Conservation Department in 2006, a pair of legs, tightly wrapped together with numerous layers of brown, now brittle, linen, was found. The legs were broken at about mid-femur and do not appear to have been cut. Before treatment of this coffin and the inner cartonnage, the fragment of the mummy was not properly titled. In 2008, Dr. Bleiberg submitted a title change: “Mummy of Bensuipet.” While it is impossible to say for certain if this mummy fragment is in fact Bensuipet, a C14 (radiocarbon) test done on a linen sample indicated that it dates to between 993 and 812 BCE, which does put it within the Twenty-first Dynasty or the period of the second occupant of the coffin.12

Once the rediscovery of ancient Egypt took hold of the hearts and minds of Western audiences in the nineteenth century, and even into the early twentieth century, the public unwrapping of mummies became a popular activity at parlor parties and scientific societies. The museum has in its collection one mummy that suffered this fate, albeit before it was acquired by the museum. What is now titled “Contents of the Coffin of the Servant of the Great Place, Teti (37.14Ec-e)” is the completely disassociated skeletal remains and associated mummy wrappings, including linen, soil, plants, and the ring of an unknown man. Based on its style, the anthropoid coffin dates to the New Kingdom, mid- to late Eighteenth Dynasty (ca. 1339–1307 BCE). The coffin and its contents were collected in 1848 by Dr. Henry Anderson and given to the NYHS.13 According to Dr. Anderson’s notes, he discovered the mummy “in the house of a peasant on the bank of the Nile, opposite Thebes.”14 An X-rad...