CHAPTER

1

BEAUTIFYING EDEN

Why Pursuing Goodness,

Truth, and Beauty Matters

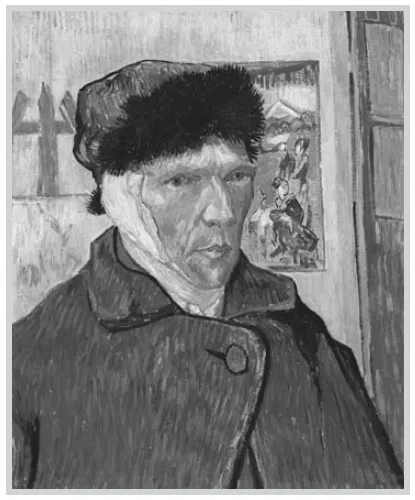

Vincent van Gogh, Self-Portrait with Bandaged Ear, 1889, oil on canvas, 60 × 49 cm, Courtauld Gallery, London

There’s so much beauty around us for just two eyes to see. But everywhere I go, I’m looking.

Rich Mullins

Henri Nouwen wrote in The Return of the Prodigal Son, “Our brokenness has no other beauty but the beauty that comes from the compassion that surrounds it.”1 Our wounds are not beautiful in themselves; the story behind their healing is. But how can we tell the story of our healing if we hide the wounds that need it? This book is about beauty. To get at it, this book is filled with stories of brokenness.

If you’ve ever tried to make a realistic self-portrait, you’ve probably made this discovery: only the truth will work. In my high school art class, I was given the assignment to draw a self-portrait. As my eyes went back and forth from the mirror to the paper, I tried to draw what I saw—with a few improvements. I gave myself brighter eyes, a more chiseled nose, greater definition in my cheekbones, and a little less of a baby face. My vanity resulted in a portrait of someone who didn’t look like me, and a B minus.

Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890) painted more than forty self-portraits. Some are not realistic at all. For example, when he was fascinated by Japanese art, he rendered himself with the distinct shaved head and Asian eyes of a Buddhist monk. But one of his self-portraits stands out as being brutally honest: Self-Portrait with Bandaged Ear. He painted it in January 1889, the year he produced The Starry Night and the year before he died of a gunshot wound to the abdomen.2

If you know anything about van Gogh outside of his art, perhaps you know he was a tortured soul. Vincent suffered from depression, paranoia, and public outbursts so disconcerting that in March 1889 (two months after the completion of Self Portrait with Bandaged Ear), thirty of his neighbors in his little village of Arles, France, petitioned the police to deal with the fou roux (the redheaded madman). The officers responded by removing him from his rented flat—the Yellow House made famous in his painting The Bedroom.3

Shortly after his eviction notice, Vincent admitted himself into an asylum for the mentally ill—the Saint-Paul asylum in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence. Back in those days, most psychological maladies were simply called “madness.” Debilitating depression, bipolar disorder, paranoia, and even acute epilepsy all fell under the umbrella diagnosis of madness. The “redheaded madman” checked himself in and remained in Saint-Rémy for a year, from May 1889 to May 1890.

What did Vincent do with his humiliation as a patient at Saint-Rémy? He painted. In fact, some of Vincent’s most celebrated works—Irises, The Starry Night, and Wheat Field with Cypresses—were created on the grounds of that asylum. During his stay, he painted the asylum’s gardens, grounds, and corridors. He painted the fields he could see beyond the asylum walls and the olive groves he would walk when he occasionally left the grounds. He painted portraits of his caregivers and fellow patients. He made his own versions of other artists’ work that he loved. And he painted self-portraits. So much beauty came from that season of his life, but so much humiliation and public rejection facilitated it.

Beauty from Brokenness

What drove Vincent to check himself in to the asylum? What made his neighbors think he was mad and petition for his removal from their community? Though there were many contributing factors, the most ubiquitous episode came several weeks before his eviction from the Yellow House. He and his flatmate, the impressionist painter Paul Gauguin, had a falling out and Gauguin left. Soon after, Vincent took a blade to his ear, cut off the lobe, wrapped it in paper, and took it to a local prostitute named Rachel, who seems to have been a friend in his community of folks on the fringes. When he handed her the blood-soaked parcel, he said, “Take it, it will be useful.”4

Word of this outburst spread quickly throughout the village, and the next morning, police found Vincent asleep in his bed, covered in blood. They took him to the hospital, and during his stay, Vincent began to count the cost of his outburst. His roommate, friend, and fellow artist had left, Vincent felt responsible. His body was permanently maimed, and his neighbors all knew why.

To add insult to injury, at the time Vincent cut off his ear, his star was just beginning to rise in the art world. After years of obscurity, he was on the verge of breaking through. So his public spectacle, which led to his eviction and detention in the asylum, piled on top of everything else a mountain of professional shame.

During his asylum year, Vincent painted more than 140 paintings—an average of one canvas every three days. Of those works, at least two were self-portraits with his bandaged ear showing. Rather than run or hide from this humiliating series of events, he captured the moment of his greatest shame.

It is hard to render an honest self-portrait if we want to conceal what is unattractive and hide what’s broken. We want to appear beautiful. But when we do this, we hide what needs redemption—what we trust Christ to redeem. And everything redeemed by Christ becomes beautiful.

Van Gogh’s Self-Portrait with Bandaged Ear indicts us. How willing are we to acknowledge the fact that we have a lot of things in us that aren’t right? A print of Self-Portrait with Bandaged Ear hangs in my office to remind me that if I’m drawing the self-portrait dishonestly—pretending I’m okay when I actually need help—I’m concealing from others the fact that I am broken. But my wounds need binding. I need asylum. And if I can’t show that honestly, how will anyone ever see Christ in me? Or worse, what sort of Christ will they see?

In Vincent’s case, the story ends with a sweet bit of irony. Self Portrait with Bandaged Ear, in which van Gogh captured the moment of his spiritual and relational poverty, is now worth millions. That canvas faithfully captures a defining moment of shame and need for rescue by showing the bandaged side, and it has become a priceless treasure. This is how God sees his people. We are fully exposed in our shortcomings, yet we are of unimaginable value to him. This is how we should see others and how we should be willing to be seen by others: broken and of incalculable worth.

In this book, we’ll explore the lives of nine primary artists, and many others by way of their connection to the nine. Each of them gave the world beautiful works of priceless art, but their stories are filled with a surprising measure of brokenness—and, in some cases, violence and corruption. Madeleine L’Engle reminds us that God often works through the most seemingly unqualified people to reveal his glory.5 So does Scripture. There is beauty in the brokenness. That’s what this book seeks to uncover, because beauty matters.

Goodness, Truth, Beauty, Work, and Community

From Socrates and Plato on down through Augustine, Thomas Aquinas, Meister Eckhart, and Immanuel Kant, philosophers and theologians have long wrestled with the question, What makes humanity so distinct from all other forms of life? Three properties of being that transcend the capacities of all other creatures, known as transcendentals, have risen to the surface: the human desire for goodness, for truth, and for beauty.

Scripture regards these three transcendentals as basic human desires that are essential for knowing God.6 Why? Because these are three properties that define God’s nature. Good and evil point to the reality of undefiled holiness. Honesty and falsehood point to the existence of absolute truth. Beauty and the grotesque whisper to our souls that there is such a thing as glory. Goodness, truth, and beauty were established for us by the God who is defined by all three.

Philosopher Peter Kreeft said, “These are the only three things that we never get bored with, and never will, for all eternity, because they are three attributes of God, and therefore [attributes] of all God’s creation: three transcendental or absolutely universal properties of all reality.”7 Everything in creation participates in each property in some way. And because goodness, truth, and beauty are desires shared in some form by all people, they are, by nature, communal. None of them were intended to exist or be fully realized in isolation. The pursuit of goodness, the pursuit of truth, and the pursuit of beauty are, in fact, foundational to the health of any community.

This isn’t just a philosophical position; it’s a biblical one. We see it in the opening chapters of Genesis. What are the first things we learn about humanity from Scripture? Here are five quick observations from Genesis 1–2.

Goodness. First, in Genesis 1, we learn that when God created us, he pronounced his creation very good.8 Goodness was a foundational part of our intended design from the beginning. To live according to the goodness inherent in our creation is a matter of both character and function; we’re called to be good and to do good.

Truth. Second, just as we were created with inherent and functional goodness, we were made to obey God. In other words, we were created to live according to God’s truth—which is absolute truth with a clear divide between what is evil and what is good.9

Consider the importance of truth. What precipitated the fall of humanity? Deception. Scripture says the serpent deceived the woman and the man, and they, in turn, lied to God and to themselves.10 That rejection of the truth has brought immeasurable sorrow upon our species, and we have been longing to reclaim some sense of what is true and good ever since. In the confines of our created world, this is a uniquely human phenomenon. We are the only creatures who are consciously concerned with goodness and truth.

Beauty. Beauty, by definition, elevates and gives pleasure to the mind and senses. It engages us on multiple levels. We participate in beauty. Genesis 1 and 2 tell us that we are made in God’s image, meaning we were created to be creative.11 We see this responsibility to create in the act of naming the birds and beasts—a task God assigned to Adam.12 While that might not seem like creation in a conventional sense, according to writer Maria Popova, “To name a thing is to acknowledge its existence as separate from everything else that has a name; to confer upon it the dignity of autonomy while at the same time affirming its belonging with the rest of the namable world; to transform its strangeness into familiarity, which is the root of empathy.”13 Creativity is a path to beauty. The creative work of naming is the work of ascribing dignity and speaking truth.

Work. Fourth, we see in Genesis that creativity is bound up in the act of work itself. Adam’s creative work was a beautifying work. He was engaged in the true “oldest profession”: landscaping, or gardening. Adam didn’t just live in Eden; he worked there.14 Our call to create stems from our first parents’ call to care for and beautify Eden. Every one of us has an ember of that fire still smoldering in our hearts. When we set out to make something beautiful, we’re drawing from that ancient instinct—however corrupted it may be from the fall—to care for and beautify Eden.

Community. Fifth, we learn that it is not good for people to be alone.15 When God created Eve, he didn’t just give Adam a wife; he gave him community. And together, Adam and Eve “created” others, in the sense that they were acting as what J. R. R. Tolkien described as “sub-creators.”16 We were created to create, and to do that in the context of community for the benefit of community.

Why Does Beauty Matter?

Genesis describes our origin as a union of goodness, truth, and beauty intended to aid in the work of building community. But we struggle to give goodness, truth, and beauty equal weight. C. S. Lewis described the struggle like this:

The two hemispheres of my mind were in the sharpest contrast. On the one side a many-islanded sea of poetry and myth [beauty]; on the other a glib and shallow “rationalism” [goodness and truth]. Nearly all that I loved I believed to be imaginary; nearly all that I believed to be real I thought grim and meaningless.17

Do you feel that same struggle? Truth and goodness can be relegated to the empirical and measurable (and the “grim and meaningless”), while the “many-islanded sea” of beauty can seem to live in another realm altogether. It’s as though goodness and truth are meant to be taken seriously, but beauty is...