- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

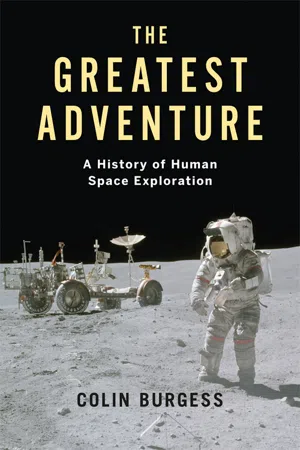

The space race was perhaps the greatest technological contest of the 20th century. It was a thrilling era of innovation, discovery and exploration, as astronauts and cosmonauts were launched on space missions of increasing length, complexity and danger.

The Greatest Adventure traces the events of this extraordinary period, describing the initial string of Soviet achievements: the first satellite in orbit; the first animal, man and woman in space; the first spacewalk; as well as the ultimate US victory in the race to land on the moon.

The book then takes the reader on a journey through the following decades of space exploration to the present time, detailing the many successes, tragedies, risks and rewards of space exploration.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Greatest Adventure by Colin Burgess in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Ciencias biológicas & Ciencia espacial. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

THE REALITY OF TOMORROW

Once considered inaccessible, Earth’s jungles, seas, deserts and North and South Poles have all been conquered over the centuries through the enterprise and exertions of countless explorers. While still unexplored terrestrial corners of this great blue planet remain, there is another seductive frontier we are only just beginning to penetrate and understand, and it is located only a few kilometres from wherever we live. It is a vertical frontier, one far more challenging and aggressively hostile than any we have ever faced before. It is space.

Throughout history, humans have experienced a compulsion to go beyond what we have previously known. One such urge has always focused its attention on our Moon, that wondrous sphere in the night sky that has long held an irresistible fascination. First, though, we needed to know more about the limits and dangers of the atmosphere that engulfs and protects us.

In the middle years of the twentieth century, heroic balloonists ascended into the frigid regions of the upper atmosphere, where the huge, gas-filled spheres above their heads literally froze to the fragility of a light bulb. After the Second World War, competitive aviators pushed their supersonic steeds to the very limits of human and mechanical endurance, coaxing planes to achieve heights where no air passed over the wings to create lift. They would find themselves entering an unforgiving environment where any aircraft – no matter how powerful or aerodynamic – can suddenly surrender to the unyielding laws of high-altitude nothingness and begin tumbling out of control.

It was not just a matter of developing aircraft to conquer this tantalizing high frontier. Pressurized cabins, breathing masks and high-altitude suits – all had to be devised and manufactured, allowing pilots to survive in the near vacuum of the upper atmosphere. Barely 18 km (60,000 ft) above ground level, the air pressure is so weak that any pilot not wearing suitable protection and breathing apparatus would be deprived of oxygen and black out from the effects of hypoxia. Furthermore, the lack of a suitable pressure suit at extreme altitudes would cause their blood to bubble and fizz like uncorked champagne. One of the few positive results of the Second World War, as in any war, was the rapid advancement of technology, which in the post-war years would assist us in taking those first tentative steps out into the space frontier.

In 1945, with the collapse of Germany’s Third Reich both inevitable and imminent, American and Soviet forces advanced through the vanquished nation, rapidly sweeping ever deeper into Germany’s heartland. One of their prime objectives was to seize equipment and personnel from the once formidable and terrifying V-2 missile programme.

American forces had soon accumulated a vast collection of rockets and rocket parts, as well as dozens of captured or surrendered scientists and technicians. These men, their families, and all the components were soon dispatched overseas to a remote desert area of the American southwest known as White Sands, New Mexico. With his tremendous experience in the field of rocketry, from simple rockets through to Hitler’s V-weapons, Wernher von Braun quickly established himself as the dominant figure in America’s missile programme.

For their part, advancing Soviet troops did not fare quite as well, but still managed to seize a modest share of the V-2 booty and capture a number of German rocket technicians. The Soviet Union’s missile development programme then continued with these new resources in the stark and forbidding outpost of Kapustin Yar, located on the empty steppes north of the Caspian Sea. In both nations the focus was on the development of missiles for potential military use, but for some of those involved there was also an unquenchable vision that more powerful variants of the rockets might one day be used to conquer space.

Our pathway to the stars began to unfold at some of the most inhospitable locations on the planet, with the work shrouded in a dark curtain of secrecy. It might be said, without too much exaggeration, that in the Soviet Union one man carried the vision of this future, along with the force of will to make it happen: Sergei Pavlovich Korolev.

Loading alcohol fuel into a captured V-2 mounted on its portable gantry at the U.S. Army Ordnance Proving Ground, New Mexico.

No one burned with quite the same energy and urgency as Korolev, who for many years was known officially as the unseen, unnamed Chief Designer of the Soviet space programme. His name, and the enormous role he played in Soviet rocketry and astronautics, would not be revealed until after his untimely death in 1966.

Korolev was born in the Ukrainian town of Zhytomyr on 12 January 1907. In his youth he trained as an aeronautical engineer at the Kiev Polytechnic Institute, following which he became interested in rocket propulsion while attending Moscow University, later joining and becoming an active member of the Gruppa Izucheniya Reaktivnogo Dvizheniya (GIRD, or Group for the Study of Reactive Motion), a club dedicated to the development and testing of liquid fuel rockets. Before long, powers within Joseph Stalin’s military recognized the impressive work being carried out by this civilian organization, and in 1933 it was taken over under his orders. The group then became known as Reaktivnyy Nauchno-issledovatelskiy Institut (RNII, or Research Institute for Jet Propulsion), the official centre for research and the development of missiles and rocket-powered gliders.

Korolevw 1938, when he was swept up in one of Stalin’s notorious purges during the barbaric period known as the Great Terror. Under spurious charges he was sentenced to ten years’ hard labour and sent to one of Stalin’s brutal Gulags, where he would spend two years working on railways and ships and in gold mines. His previous work in rocketry eventually came to the notice of a former prisoner, famed aircraft designer Andrei Tupolev. While still regarded as a political prisoner, Korolev was permitted to work on Tupolev’s design team.

Sergei Pavlovich Korolev, the Soviet space programme’s secret Chief Designer.

Late in 1944, Korolev was authorized to form his own rocketry team and within three days had put together a proposal for a Soviet equivalent to Germany’s V-2 missile. His rockets succeeded, although the expected range of the missiles was considerably less than that of the V-2. The following year he was sent to Germany in order to coordinate the recovery and assessment of V-2 parts and to recruit many of the experts who had worked on the destructive rockets in the latter years of the war.

On his return to the Soviet Union, Korolev was named as chief engineer in charge of a design team responsible for the development of a cosmetically modified, Soviet version of the V-2, which later became known as the R-1. Korolev would continue his pioneering work, and, following the death of Stalin in 1953, began enjoying the powerful support of the new Soviet premier, Nikita Khrushchev.

Several years later, the privations and working conditions he had endured while held in the Gulag camps contributed to Korolev’s premature death in 1966, unfortunately at one of the most critical phases of the Soviet space programme. Following his death, Korolev’s name no longer remained a closely kept state secret, and he quickly became a revered icon of Russian rocketry. It is a tribute to his work that both the rockets and spacecraft he helped design and develop, with some later modifications, are still flying today.1

Dogs Riding Rockets

Under the watchful eye of Sergei Korolev, the Russians are believed to have launched the first of their captured German V-2 rockets on 18 October 1947, and their first modified prototype R-1 took to the skies from Kapustin Yar, on the banks of the Volga River, on 17 September the following year. Unfortunately the R-1 veered off course after launch, but a second test on 10 October proved more successful.

In order to conduct biological studies of organisms in space flight, the R-1B geophysical rocket was fitted with a recoverable payload section, which included a parachute system and a ‘skirt’ of six external drag brakes. During the separated capsule’s descent it would free-fall for several minutes until it reached thicker air. The braking flaps then extended to steady and slow the capsule, after which a drogue chute would deploy, followed by a larger parachute.

It had already been decided that once larger nose cone capsules had been developed, the first creatures to occupy them would be small dogs. These would be ‘recruited’ from the streets of Moscow, which meant they were tough animals conditioned to a hard life, inured to hunger and freezing temperatures. Armed with a list of requirements, zoologists and other canine specialists were sent around Moscow to hunt for suitable candidates from among the common street type or mongrels. Several suitable dogs were also purchased from owners or dog pounds. Tests had shown that females were more sedate and less inclined to become fractious under pressure than males and so were selected for this reason. As well, the specially designed space suit they would wear was fitted with a device to collect urine and faecal matter, and was only manufactured to suit females. Each animal’s height, length and weight were carefully recorded, and each was given a cute identifying nickname.2

Dr Nikolai Parin from the Soviet Academy of Medical Sciences once explained the reason behind the selection of canines as subjects for space travel. ‘The Russian dog has long been a friend of science,’ he stated. ‘We have collected much information on our four-footed friends. Their blood circulation and respiration are close to man’s. And they are patient and durable under long experiments.’3 The selected dogs underwent preliminary testing and were divided into three categories according to their nature. The first group comprised even-tempered animals; the second, those who were restless and excitable; and finally there were the sluggish or slow dogs. The first school of even-tempered canines were destined for training specifically for long space flights and included such dogs as Strelka (Little Arrow), Belka (Squirrel), Lisichka (Little Fox), Chernushka (Blackie), Zhemchuzhnaya (Little Pearl) and Laika (Barker).

The dogs’ breathing, heartbeats and temperatures were checked daily. They were X-rayed and taken on high-altitude aircraft tests to become familiar with the sensations of flight. Each was trained to wear a lightweight space suit, to be strapped into a confining canister and to eat off special trays. Through other tests, the dogs grew accustomed to the effects of vibration. They were then strapped into centrifuge chambers and whirled around at high speed to gauge their reaction to the forces of strong acceleration. Meanwhile, some of the other dogs were being trained for test ballistic space shots, touching on space, together with a menagerie of other small animals.

Laika looks over the capsule that will one day carry her into space.

The first programme of six experimental R-1 rocket launchings carrying dogs took place between 1951 and 1952. Nine of the selected canines took part in these short, high-altitude geophysical flights, with three making two flights. The animals were checked post-flight and reported to be in good health. Nevertheless, Soviet scientists would not release details of these experimental rocket flights for several years; back then (and even to an extent now), most information was sketchy. Among the dogs known to have flown on these tests were Al...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Prologue

- 1. The Reality of Tomorrow

- 2. First into Outer Space

- 3. Into Orbit

- 4. Stepping into the Void

- 5. Tragedy on the Launch Pad

- 6. Eyes on the Moon

- 7. One Giant Leap

- 8. Soviet Setback and Skylab

- 9. Recovering the Soyuz/Salyut Missions

- 10. Space Shuttles and the ISS

- 11. Expanding the Space Frontier

- Epilogue: Our Future in Space

- References

- Select Bibliography

- Acknowledgements

- Photo Acknowledgements

- Index