- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

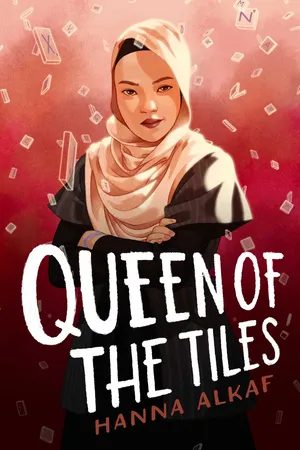

Queen of the Tiles

About this book

They Wish They Were Us meets The Queen’s Gambit in this “stunning…unforgettable” (Publishers Weekly) thriller set in the world of competitive Scrabble, where a teen girl is forced to investigate the mysterious death of her best friend when her Instagram comes back to life with cryptic posts and messages.

CATALYST

13 points

noun: a substance that speeds up a reaction without itself changing

When Najwa Bakri walks into her first Scrabble competition since her best friend’s death, it’s with the intention to heal and move on with her life. Perhaps it wasn’t the best idea to choose the very same competition where said best friend, Trina Low, died. It seems that even though Najwa is trying to change, she’s not ready to give up Trina just yet.

But the same can’t be said for all the other competitors. With Trina, the Scrabble Queen herself, gone, the throne is empty, and her friends are eager to be the next reigning champion. All’s fair in love and Scrabble, but all bets are off when Trina’s formerly inactive Instagram starts posting again, with cryptic messages suggesting that maybe Trina’s death wasn’t as straightforward as everyone thought. And maybe someone at the competition had something to do with it.

As secrets are revealed and the true colors of her friends are shown, it’s up to Najwa to find out who’s behind these mysterious posts—not just to save Trina’s memory, but to save herself.

CATALYST

13 points

noun: a substance that speeds up a reaction without itself changing

When Najwa Bakri walks into her first Scrabble competition since her best friend’s death, it’s with the intention to heal and move on with her life. Perhaps it wasn’t the best idea to choose the very same competition where said best friend, Trina Low, died. It seems that even though Najwa is trying to change, she’s not ready to give up Trina just yet.

But the same can’t be said for all the other competitors. With Trina, the Scrabble Queen herself, gone, the throne is empty, and her friends are eager to be the next reigning champion. All’s fair in love and Scrabble, but all bets are off when Trina’s formerly inactive Instagram starts posting again, with cryptic messages suggesting that maybe Trina’s death wasn’t as straightforward as everyone thought. And maybe someone at the competition had something to do with it.

As secrets are revealed and the true colors of her friends are shown, it’s up to Najwa to find out who’s behind these mysterious posts—not just to save Trina’s memory, but to save herself.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Queen of the Tiles by Hanna Alkaf in PDF and/or ePUB format. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Print ISBN

9781534494565eBook ISBN

9781534494572CHAPTER ONE Friday, November 25, 2022 One Year Later

INERTIAseven pointsnounfeeling of unwillingness to do anything

Most people play casual games of Scrabble in their living rooms, squabbling good-naturedly for points over sets their parents bought them in the hopes that it would be “educational.”

No, actually, this is a lie. Most people probably barely even think of Scrabble at all, and the sets they do get wind up gathering dust in the very backs of shelves and cupboards, forsaken in favor of games like Snakes & Ladders or Monopoly or Clue or Twister. You know. Fun games.

The tournament circuit is a different world. Here, people play Scrabble as a game of probabilities and cunning strategies, a math problem to be solved. Here, we carry around reams of paper crammed so full of words it looks like they’re teeming with ants; we recite anagrams with such rapid speed that each syllable hits you with the force of a bullet; we can tell you the most probable combination of letters you’ll get on a rack (it’s AEEINRT, for the record) with which you can score a bingo—that is, to use up all seven letters at once and earn an additional fifty-point bonus. Here, we never stop thinking about Scrabble.

For most of my peers, words are little more than point-amassing units, each tile merely a stepping stone for building high-scoring pathways to victory. For me, the words aren’t just points: They’re the whole point. I collect them, hoard them like a dragon hoards its treasure, reveling in their strange, alien meanings, the feel of them in my mouth. The words are how I process the world. People like Josh say I waste precious brain space clinging to their definitions. “There are one hundred eighty thousand possible combinations of letters you need to know,” he told me once. “Caring about what they mean is beside the point.” But how can you not? Take AEEINRT, for instance. Picture each letter in your head—the reassuringly symmetrical A, the graceful curve of the R—and rearrange them in your head, over and over again. Most people will settle for RETINAE or TRAINEE, but why go for such clumsy, obvious choices when you have the delicate wonder of ARENITE, a sedimentary clastic rock? That gives you the equally lovely CLASTIC—those bookending hard Cs so satisfying as they roll off the tongue—which means composed of fragments, and to FRAGMENT means to break into pieces, and that’s what I’m doing right now, aren’t I? Sitting here in the driveway of a generic three-star hotel, falling apart.

“What are you so afraid of, Najwa?” my mother asks. She’s trying for a gentle tone, but the note of impatience that she can’t keep from sneaking in kills that vibe. My mother has a fondness for things that endure: Birkenstock sandals, melamine dishes, old and usually racist actors who never seem to die. Tough things. Unbreakable things. She likes them low on maintenance, high on durability.

This is not me: One year later and I’m still a mess. Tiny things send me into panic spirals. I lose things. I forget things. I walk from one place to another and then have to walk back because I can’t remember why I ended up there in the first place. It’s as if Trina’s death cracked me open, and now pieces of me keep escaping, scattering themselves everywhere. It’s funny—well, maybe not to anyone but me—to ENDURE also means to suffer something patiently, and my mother is definitely suffering. My therapist has told her to respect my grieving process, but Mama’s patience, like the cheap cotton T-shirts I buy from fast fashion retailers that she hates (“So low quality!”), wears thin fast.

I fiddle with the phone in my hands.

Me: She’s so tired of meAlina: So am I. Doesn’t mean we don’t love you, mangkuk.

Alina and I have been sending each other WhatsApp messages for the past few hours. She may only be fourteen to my sixteen, but my little sister knows to be on hand when I’m about to do something big, something that could potentially send me careening off-course.

Mama clicks her tongue now as she sits at the wheel of the idling car, waiting for me to reply, to pull myself together, to get my things and get out—or preferably all three at once, I’m guessing. It’s been more than four hours since we left our home in Kuala Lumpur to get to this shining, anonymous box of a hotel in Johor Bahru where the tournament is taking place this weekend; this is more time than we’ve spent with just each other since I was about ten, and neither of us knew quite how to handle it. She tolerated my music for approximately twenty-three minutes (a playlist heavy on K-pop, indie rock, and Taylor Swift) before making me switch to her favorite radio station (playing “easy listening hits,” which seems to translate to “absolutely no songs from the past ten years”) for as long as it took to get out of range. Then when the music gave way to nothing but static, she made me plug in her iPhone so we could listen to some sheikh reciting Quranic verses. Verily, in hardship there is relief.

“It’s a lot to take in, okay?” I fiddle with the friendship bracelet tied around my wrist, then pull the sleeves of my black top down low so only the tips of my fingers peek out of the edges. I’m always cold these days. “It’s been a year. I’m just nervous.”

“Nervous? Buat apa nak nervous?” Mama glances up at the rearview mirror and adjusts her deep blue headscarf. In her youth, she was a beauty queen; we have sepia-tinted pictures of her poised and smiling on stage, her hair lacquered to terrifying heights, her tight kebaya skimming her curves. Now she adheres to a strict regime of creams and potions designed to scare off any wrinkle foolhardy enough to try making its presence known. “There’s no reason to be. You know this game inside out. You’ve been playing Scrabble most of your life, thanks to your father and me.” (My mother likes to take credit for my word-wrangling prowess, such as it may be, because she and my dad bought me my very first set. “It will help improve your English,” she told me on my eighth birthday, when the present I tore open so eagerly held my first Scrabble set instead of the long-desired Rock Star Barbie I’d begged for with the spangled clothes and the hot pink plastic guitar, and I had to bite my tongue to keep from saying something I’d regret.)

Mama continues, not waiting for my reply. As usual. “You’re good at it. And you’ll be with all your friends.”

“What friends? I only had one.”

Mama stiffens. Like most of the Malaysian parents I know, she doesn’t like it when I bring up “sensitive” topics. She especially doesn’t like it when I bring up Trina, which means I instantly feel like I need to yell it in her face: Yes, that one, Trina, you know, my best friend in the whole world, the one I saw die right there in front of my eyes, at this very hotel in fact. You remember. Mama never did like Trina. Oh, she never said so outright—she was much too big on etiquette, on keeping up appearances, on maintaining face for that sort of thing—but there was a telltale sniff any time her name came up, as if just the sound of it gave her allergies, and I’d catch her discreetly eyeballing Trina’s outfits with distaste whenever she was in sight. Trina came with too many “toos” for my mother to stomach: skirts too short, tops too tight, tongue too sharp, gaze too knowing.

“Yes, well. That was a long time ago. Maybe this is what you need to get some closure.”

CLOSURE, I think. A feeling that a traumatic experience has been resolved, but also just the act of closing something—a door, an institution, this conversation that is making my mother ridiculously uncomfortable. Only how can anything be resolved when we never figured out what caused Trina’s death in the first place? No explanations, no conclusions, only a door forever ajar, letting a million what-ifs drift in as they please.

“Dr. Anusya says it’s time for you to move on, get back to the things you love,” Mama reminds me now. “And you love Scrabble.”

It’s true. I do. There was a time, after it all happened, when even the sight of a tile was enough to set off a tidal wave of anxiety sweeping through my body. But we’ve worked our way up to this point so gently, so carefully, from casual games in Dr. Anusya’s plush office to local Scrabble club meetups to small competitions and now this, the Word Warrior Weekend that takes place every November during the school holidays: part elite tournament, part sleepover, all awkward teenage hormones and chaste, chaperoned social events in between. Scrabble is the one thing in which my brain hasn’t failed me, and each remembered word is a life raft on days when I feel like I’m drowning. Nobody’s dictating my pace here; nobody’s forcing me to move on. I want to do this. I need to do this. So why is uncertainty gnawing away at the frayed edges of my nerves? “Maybe I’m just not ready yet,” I say, and I hate how small my voice sounds.

As if Alina somehow knows how I’m feeling, my phone buzzes again.

You’ve got this, Kakak.

My mother checks her watch surreptitiously; I don’t think I’m supposed to notice, but I do. “Come on, sayang. Berapa lama lagi nak hidup macam ni? It’s time to get out of this cave you’ve built around yourself and get back to being… you.” This time, the gentleness rings true, and my immediate instinct is to want to cry. Nothing undoes me quite like people being nice to me. She’s right, and I hate that she’s right, but I can’t keep living like this.

“Yeah, okay,” I say. I sling my backpack over one shoulder, check the front pocket for my signed permission slip, grab the duffel that holds enough clothes for the weekend. “I’ll see you on Sunday.”

“Have fun,” she says. “Call me to check in.” She gives me one last look, a slight frown on her face. “And fix your tudung. Senget tu.”

I sigh. Of course her final words to me would be to fix my crooked headscarf. What else did I expect? “I will.” The moment is over. I don’t offer a hug or kiss, and she stares straight ahead because she doesn’t expect either one; we’re just not that type of family.

“See you,” I say as I struggle to haul myself and my baggage, seen and unseen, out of the car. Grief is a heavy thing; it weighs you down, turns all your limbs to lead. There have been so many times in the past year when I’ve wanted to stop, wherever I was—in the cereal aisle at the supermarket, in the middle of doing jumping jacks during PE, in the middle of a shower—when I’ve had to fight the urge to just lie down, just rest, feel the coolness of the floor beneath my skin. Bet my mother would have hated that.

“Bye,” she says.

I slam the door shut as if closing it tight enough will trap all my fears and worries and memories in there, as if shedding them means I, too, can become a thing that endures.

CHAPTER TWO

ANAMNESISeleven pointsnounability to recall past events

I step forward. The doors glide open. I step back. The doors glide shut.

I do this a few more times. I know the doorman in his sleek gray uniform with the gold trim is staring at me, and he’s probably not the only one. I just can’t make my feet go any farther, can’t make them take that next step beyond the big glass doors and into my past. So I do this dance, feeling the weight of my duffel bag press against my shoulder, feeling the blast of too-cold air-conditioning brush against my face, feeling the surge of long-lost memories crash into my brain, as cars come and go and people mill past me.

I pull up my phone and open up my DMs on Instagram.

I don’t know if I can do this without you.

Then I put it away again and stare at the doors before me. I’m not expecting a reply.

Do you know what happens when there’s a sudden, unexplained death in a public space like a hotel? They call in the police, who drive up in trucks known as Black Marias even though they aren’t actually black, but a deep, dark blue. They treat it like a crime scene. By extension, therefore, they treat you like a suspect—at least, until they have no reason to. Until you give them a reason not to.

Oh, they were very careful not to tell us that. We were fifteen-year-olds, after all. We’d just watched our friend die. We were a bunch of scared, confused minors they somehow still needed to extract information from. They tiptoed so carefully around us it was like being in the middle of a performance of Swan Lake. But we knew anyway.

Not that I was much help. A couple of hours after it happened, a very patient young sergeant took us each into one of the hotel’s small meeting rooms. I watched familiar faces go in and out, one by one—though my brain, fueled by anxiety and running at a bazillion kilometers an hour, only really managed to register a trembling Yasmin and a stone-faced Mark—the sinking feeling in my stomach deepening with each one, waiting for that discreet tap on my shoulder, the polite request to “please follow me.”

The room was cold. The sergeant was warm. The questions were endless: Where were you when the incident happened? Can you tell me in your own words what you saw? Were you close to the victim? Was there anything off about her leading up to the game? Was she upset? Was she agitated? Did she complain of not feeling well? I stammered and I stumbled, not understanding, not knowing what to say. It took me a while to even register that “the victim” meant Trina, and when I realized it, I started crying all over again. I was still crying when my mother burst into the room, shirt rumpled from the long drive down from Kuala Lumpur, hijab all askew. I remember taking in the sight of that hijab, the one clue to how absolutely agitated my usually poised mama was in that moment, and feeling my heart crack a little further.

“What is the meaning of this?” my mother had said, all of five feet one point five inches and yet somehow staring down the suddenly groveling sergeant. “Why are you harassing my daughter like this?”

“I’m just asking her some basic questions, puan.…”

“Questions? What questions? What right do you have?” She squinted up at him and I swear I saw him go slightly gray. “She is only fifteen years old! A fifteen-year-old who has just gone through major trauma! Can you even ask a fifteen-year-old questions like this without an adult present?”

“Oh, can puan, can,” the sergeant says quickly. “It’s perfectly legal, trust me.”

“Trust you?” Mama folded her arms, her expression stormy. “Not bloody likely. Typical incompetence. Come, Najwa, we are going.”

“We are not done here, puan!” the sergeant spluttered, and for a second I almost felt sorry for him. Bet he thought this would be a nice, easy gig, all done by teatime.

“You can give her time to regain her composure, and when she ha...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Author’s Note

- Chapter One

- Chapter Two

- Chapter Three

- Chapter Four

- Chapter Five

- Chapter Six

- Chapter Seven

- Chapter Eight

- Chapter Nine

- Chapter Ten

- Chapter Eleven

- Chapter Twelve

- Chapter Thirteen

- Chapter Fourteen

- Chapter Fifteen

- Chapter Sixteen

- Chapter Seventeen

- Chapter Eighteen

- Chapter Nineteen

- Chapter Twenty

- Chapter Twenty-One

- Chapter Twenty-Two

- Chapter Twenty-Three

- Chapter Twenty-Four

- Chapter Twenty-Five

- Chapter Twenty-Six

- Chapter Twenty-Seven

- Chapter Twenty-Eight

- Chapter Twenty-Nine

- Afterword

- Acknowledgments

- About the Author

- Copyright