Chapter 1

IT HAD BEEN ELEVEN NIGHTS since I’d slept.

I don’t mean I’d tossed and turned in bed and had difficulty falling, or staying, asleep.

I had not slept. At all.

I’d been awake for the past two hundred and sixty-four hours. I’d read on the American Pediatric Association website—not a site that I would usually visit, but when you’re awake at three a.m., these are the things you find yourself doing—that the recommended amount of sleep for thirteen-year-olds is between eight and ten hours a night. As a thirteen-year-old girl who had gotten no sleep for two hundred and sixty-four hours, I had found this information quite disturbing.

The thing was, though, that I felt absolutely fine. I’d been to enough sleepovers to know what the day after not getting enough sleep was supposed to feel like, and I didn’t feel that way. I didn’t feel grumpy or sluggish or even the tiniest bit tired. I hadn’t as much as yawned in the past ten days. If anything, I felt more awake than usual. In the past few nights, I had:

- Reread all the Harry Potter and Percy Jackson books.

- Checked and rechecked all my homework.

- Finished a paper on the digestive system that wasn’t due until the end of the semester.

- Reorganized the clothes in my closet by type, then material, then color, then back to type.

- Watched eight seasons of Friends and most of Gilmore Girls.

- Taught myself how to moonwalk.

- Tried—and failed—to teach myself how to apply eyeliner.

- Learned how to French, fish tail, and Dutch braid my hair.

You can get a lot done between the hours of ten p.m. and seven a.m. when no one is telling you to get off the internet (my parents) or trying to get you to watch funny cat videos (my little brother, Riley).

Based off a quick How long can a person stay awake? Google search, I’d learned that I was now just a few hours away from breaking the record, which was set by a high school student named Randy Gardner, who, in 1964, in a total last-minute, let’s-get-out-of-homework move, decided that going without sleep would be his science fair entry.

Things didn’t work out so well for Randy. After four days without sleep, he couldn’t remember how to play chess, and by day six, snakes and ladders was too difficult for him. Ever since I’d read about Randy’s board game wipeout, I’d been challenging my dad to a chess match every night. And every evening I’d beaten him. Although this—and my shockingly good grades—made me worry less about the state of my brain, I wasn’t so sure about the rest of me. So, I’d insisted that Dad, who didn’t believe me and thought I was just experiencing long and hyperrealistic dreams, take me to the doctor.

I was scheduled to meet with Dr. Loomis before school in the morning. I glanced at my phone. It was five a.m. In just a few hours I’d be talking to someone who’d have answers about what was happening to me. Finally. Other than finding out about the recommended sleep cycles of teens, the internet had been useless. I’d spent tens of hours online reading about all the things that were not happening to me, like not being as smart as usual (see Randy Gardner’s chess playing) and bone-crushing tiredness.

The only person I told besides Dad was my best friend, Romy, who went straight to the Dracula option. Mom was halfway across the world on a tiny island that had no cell service, so I couldn’t tell her about what was going on. And even if Mom had been here, I wasn’t sure I’d tell her anything. Mom overreacted about things—well, maybe not things, but she overreacted about me—and I was afraid of what she’d say and do if I told her that I no longer needed to sleep. Dad’s reaction was understandable, though—I did look absolutely fine (same medium-length curly brown hair, same palish skin with a smatter of freckles, and same hazel eyes), and my chess playing was outstanding. I’d won every game. Romy believed me straightaway because, as she said, why would I make something like this up? We had discussed the Dracula possibility during a sleepover at her house—that’s the kind of friend Romy is; she suspected I might be a vampire, and she still let me share her bedroom—and then ruled it out. I hadn’t developed any strange, bloody cravings, and I didn’t sleep at all, unlike vampires who sleep during the day and roam about at night looking for necks to bite.

I was sure Dr. Loomis wouldn’t want to chat about bloodsucking creatures. She was a doctor. She’d have to know why I had stopped needing to sleep, and she’d have answers. I had just a few more hours to wait until I found out why I, unlike every human being on the planet—according to the American Sleep Association—was able to function normally without any sleep.

A noise from Riley’s room made me poke my head in—I sort of hoped he was awake; it got boring sometimes, just hanging out on my own hour after hour, night after night—but he was fast asleep. He must have been dreaming. I sat down on the comfy chair beside his bed and listened to the sounds coming from the street below. We lived in Brooklyn, so even in the deepest, darkest part of the night, there were noises outside: car doors closing, the hum of garbage trucks, and distant sounds of ambulances and fire sirens.

Riley let out a little burble of laughter and kicked his legs, throwing the covers off. I reached over and put the comforter back on top of him. His head was resting on his favorite book, The Big Book of Outrageous Facts. He wasn’t able to read most of it, but it didn’t stop him from quoting it all the time. Just before he’d gone to bed, he’d told me that he’d read there were more saunas than cars in Finland. (I didn’t think Riley even knew what a sauna was.) I gently pulled it out from under his head and put it on the bedside table. I noticed that the light coming in from outside the bedroom window was changing from dark to hazy gray. It was almost morning.

I went back to my room and opened my closet, where I saw a T-shirt that Mom had given me a couple of weeks ago. It said, I AM SMART! I AM STRONG! I CAN DO ANYTHING! (It was ridiculous-looking, but not as bad as the “surprise” Mom had put in my room just before she left for her trip. I was still mad about that.) For a fraction of a second I wondered what John Lee, the boy I liked, would think of it. Could this T-shirt be the conversation opener I’d been looking for? No, definitely not. I’d be better off wearing Riley’s Captain Underpants pajamas to school.

I pushed the T-shirt aside and picked out a pale yellow top and jeans. Then I walked downstairs and headed into the kitchen to make breakfast. I was just about ready to flip my French toast when I heard the old floorboards upstairs creaking, letting me know that my dad had gotten out of bed.

I had broken a world record. My twelfth day without sleep had begun.

Chapter 2

BY THE TIME DAD AND Riley came downstairs, the kitchen table looked like a hotel buffet. Omelets, pancakes, toasted bagels. I’d even sprinkled icing sugar on the French toast. Back when I used to sleep, I’d just grab a granola bar and a banana on my way out the door, but the no-need-for-sleep me was a whiz in the kitchen, whisking and sieving and poaching breakfast to the amazement and delight of my dad and little brother.

“This is great, Cia,” said Dad, clinking my glass of orange juice with the bottle of maple syrup. “If you keep this up, I’ll have to buy new pants.” He patted his stomach, which was straining against his waistband. Dad should have bought new pants about ten pounds ago.

“I want new pants with frogs on them,” said Riley, who loved all animals, especially the ones that could fit in his pocket. “Rocket frogs can jump six feet.”

Riley slid off his chair and hunkered down onto his ankles. Then he propelled himself across the kitchen. I ran and grabbed his backpack off the floor—I’d just put his lunch and juice box in it—making sure he didn’t crash-land on top of it.

The frog facts continued on the drive to Riley’s school. It was actually nice to hear about poisonous amphibians instead of thinking about what Dr. Loomis would say when she heard I’d stopped sleeping. I missed Riley’s chatter after Dad and I dropped him off and headed for the pediatrician’s office. For the rest of the drive, I picked at a hangnail and tried not to think about Dr. Loomis giving me some terrible diagnosis or—and this would be even worse—Dr. Loomis not being able to figure out what was going on with me. What if she insisted that I check in to a lab to be studied? It’d be just me and the guinea pigs.

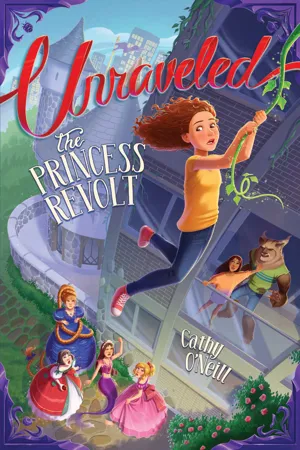

At the office, Dad and I were shown to the princess room. All the exam rooms at Dr. Loomis’s were decorated with a kid-friendly theme, and Snow White, Sleeping Beauty, and the rest of the gang from the Magic Kingdom gazed down at me from their pictures on the walls. It was the kind of room you’d be excited about if you were six—not so much if you were thirteen. (Though I still liked the Lego/Star Wars room. That one was cool.) I was so happy that Dad was with me and not Mom. Mom would hate the decorations so much, she’d probably ask for us to be moved, or she’d grab a Sharpie and draw mustaches on all the princesses.

Mom hated Disney princesses the way other moms hated sugary nonorganic snacks. It wasn’t just Disney princesses, though. Mom hated any stories—especially magical ones—that, in her opinion, showed girls as being weak and helpless. Even though I felt ridiculous sitting here with Rapunzel and Ariel, a part of me was still mad at Mom for not letting me dress up as Belle for Halloween when I was five. All I’d wanted was to wear those gorgeous yellow gloves and the swishy dress that my grandma, Dad’s mom, had sent to me—but Mom packed it all up and sent it back, muttering about “one-dimensional twits” and complaining that they were “destroying girls’ self-esteem.” I still didn’t understand why she got so mad. They were just fairy-tale characters.

“So, Cia, what’s going on?” said Dr. Loomis, coming in to the room. My name is Boadecia, but fortunately, no one but my family and best friend, Romy, knows that. Everyone calls me Cia. Mom was getting a PhD in mythology when she was pregnant with me and decided to name me after a Celtic warrior queen who—if legends are to be believed—took on the whole Roman army. It’s a lot to live up to. She’d wanted to name my brother “Heimdall” after some Norse god, but eight-year-old me told her that it was the ugliest name that I had ever heard. Riley owes me forever for saving him from nicknames like Heimy or, even worse, Heinie.

“I’m not sleeping,” I said, feeling my chest tightening as I spoke. I had insisted that Dad take me to the doctor, but now that I was about to tell someone other than my dad and Romy about my totally weird situation, I felt nervous. What if Dr. Loomis told me that not needing to sleep was a symptom of some horrific, super-rare disease? That would be terrifying. Or that somehow I’d accidentally done something mortifying that was causing my no-sleep condition. I thought about T.J. Sullivan, a boy in my grade, who—when he went to the school nurse because of a nosebleed—found out that he’d had a popcorn kernel stuck up his nasal cavity for months. Some students thought that it was hilarious; others thought that it was disgusting; but either way, it was all anyone talked about for a couple of days. I didn’t want students comparing me to the kid who had stuck popcorn up his nose.

“I haven’t slept for days,” I continued. In fact, I’ve broken the world record.

“Not sleeping for days,” confirmed Dr. Loomis thoughtfully, smoothing down her hair. “Well, that’s not good.” She gave me a knowing look and a nod that seemed reassuring, as if she’d heard this complaint hundreds of times before.

I felt my shoulders sag with relief. Maybe Dr. Loomis had loads of teenage patients who didn’t need to sleep. A tiny seed of hope opened up inside me. Maybe what I was going through was normal.

“A lot of kids your age have issues with their sleep. Are you waking up during the night?” She took off her glasses and cleaned them with the hem of her white coat.

“No.” I shook my head. “I can’t fall asleep.”

“So, you’re having trouble falling asleep?” she asked, tapping her pen on the top of her laptop.

“I can’t fall asleep,” I repeated. “At all.”

“So, how many hours of sleep are you getting on most nights?”

I felt a flash of frustration and despair. Was Dr. Loomis just ignoring what I’d said? I’d told her that I couldn’t fall asleep. And if I couldn’t fall asleep, then obviously I couldn’t sleep. How could I be getting any hours of sleep if I couldn’t fall asleep in the first place?

“I’m not…,” I began. I paused, trying to keep my voice steady. I felt like I might start shouting. I glanced over at Dad, who was looking at me with a mixture of confusion and concern on his face.

“I’m not sleeping at all,” I said firmly. “I know it sounds impossible, but I don’t need to sleep anymore.”

Dad inhaled deeply and shifted his position in the chair.

“I close my eyes, but…” I stopped, staring down at the floor. I didn’t want to see Dad’s and Dr. Loomis’s reactions, but I had to say it. “I haven’t slept for eleven nights.”

Dr. Loomis laughed so loudly, I looked up. “That’s just not possible,” she said, an expression of amusement on her face. She looked at me and then at Dad, then back at me.

“I’ve told her that,” said Dad, leaning forward in his chair.

“But I haven’t slept for eleven days,” I snapped, feeling angry about Dr. Loomis’s burst of laughter and the Aren’t-kids-just-wacky? glance she and Dad had exchanged.

“Okay,” said Dr. Loomis soothingly, raising both her palms. “Let’s just take a look, Cia.” She scooted her stool toward the examination table. “How do you feel? Have you missed school because of this?”

“I haven’t missed any school.” I sighed, sinking back into the chair. The rush of adrenaline I’d felt at not being believed was fading, and the nervous feeling was coming back. I didn’t like the curious way Dr. Loomis was looking at me. The line between her eyebrows was deepening as she creased her face into an expression of confusion.

“Okay, Cia,” she said, standing up. “Let’s just check on a few things.” She pointed toward the examination table. I walked over to it and hopped on, my l...