one ADELE

— June 1918 —

No. 1 Canadian Casualty Clearing Station, near Adinkerke, Belgium

Adele focused on the tips of her fingers, numb from being clamped around a metal surgical bowl for so long, then she shifted her attention to the wrists supporting them and silently demanded they stop shaking.

“Lieutenant?”

She held out the bowl. “I’m sorry, Dr. Bertrand.”

Tink. A tiny sound of victory as a metal fragment dropped in. Adele steeled herself, determined to remain still as stone. Dr. Bertrand’s use of her rank had that kind of effect. She’d never felt entirely deserving of the official title, but every one of the Canadian nurses had been given the same one upon enlisting. “Lieutenant Savard” gave Adele a perceived position of authority, which came in handy around some of the soldiers she tended.

Adele had never assisted with a trepanning before, an ancient procedure where a hole was cut into a patient’s skull to relieve pressure and gain access to any foreign matter lodged within. What was throwing her off wasn’t the sight of the poor man’s exposed brain or the blood. That rarely bothered Adele anymore. It was the exhaustion that rattled through her bones like a train. She’d been on her feet for sixteen hours today, eighteen yesterday. In between, she’d curled up in the nurses’ tent, grabbing a few hours of sleep before returning to duty. For the past ninety minutes, she’d been standing next to Dr. Bertrand, holding the bowl as he fished bits of shrapnel out of the soldier’s brain. She couldn’t understand how he managed to stay awake long enough to do it.

A boom sounded in the distance, and she shifted her weight. Stationed as they were so close to the French border, less than an hour from the busy port of Dunkirk, she was no stranger to the thunder of the big guns.

“That should…” Dr. Bertrand murmured, peering into the site.

Adele raised her chin, then let it drop. If she saw what Dr. Bertrand was doing, she would want to ask questions. He was a nice man, but he wouldn’t have the energy to operate on a man’s brain and answer a woman’s questions at the same time.

His dark brow creased with concentration. “No, wait. Magnet, please.”

Clutching the bowl in one hand, Adele passed the magnet to him with the other. A new blast jostled a lamp overhead, sprinkling the workspace with a light shower of dust, and Dr. Bertrand paused for a moment, waiting for it to settle, before returning his attention to the man on the table.

“Ah, there it is. I’d never have found it without the magnet.”

She saw his smile lift behind the cloth mask as he held up the forceps again, a tiny sliver of metal clamped between its tips. He dropped it into Adele’s bowl then stepped back so his surgical assistant could close the site.

Dr. Bertrand slid his mask beneath his chin and nodded at Adele. “Excellent job, Lieutenant. I think you’ve earned a good night’s sleep. I’ll see you in, what, four hours?”

She huffed a laugh, feeling the tension release as she lowered her aching arms. “Sounds about right.” Then, out of habit, she cast a worried glance at the patient, still unconscious.

“Time will tell,” he said. “These types of surgeries are so intricate. Even if he survives, we have to hope nothing critical was injured in the brain. Just keep a close eye on him.”

Adele untied her apron and deposited it in the laundry bin along with so many other pieces of bloody cloth, then left the main hospital tent, stepping into the early summer chill of night. The air carried a suggestion that rain was, once again, on its way. Behind her, the agonized howls of men and the concentrated voices of doctors and nurses faded away as the thuds of explosions travelled across the landscape beyond. Bursts of light blanched the distant battlefield, but Adele didn’t bother to stop and watch the spectacle. She’d seen it before. Besides, her vision was blurring around the edges with fatigue as she made her way through the endless maze of sheets and bandages drying on lines, then around temporary huts, buildings, and tents toward the nurses’ quarters.

No. 1 Canadian Casualty Clearing Station was more than a hospital, it was a village unto itself—a square mile of various structures surrounded the main hospital tent, all of which could be relocated depending on the proximity of the fighting. Since Adele had arrived three years ago, the clearing station had already moved to a few different spots between France and Belgium, always as close as possible to a railway so they could treat the injured men coming from the battlefields.

Inside her tent, Adele found Hazel and Minnie sound asleep, Minnie’s snores a soothing hum. Lillian wasn’t in her bed. She was likely still in the hospital tent, tending to some poor soul. Not one of the hundreds of Nursing Sisters who had come to Europe from Canada would ever leave a patient in need of medical care or a compassionate ear, and Lillian was no exception. It was in her blood to care for the broken and bruised, just as it was in Adele’s.

Before the war, Adele had been eager to see the world beyond her quiet town of Petite Côte on the Detroit River. When her mother had encouraged her and her sister, Marie, to attend nursing school in Toronto six years ago, Adele had jumped at the chance. Two years later, the war broke out, and a year after that, Adele told her mother that she was going to enlist with the Canadian Army Medical Corps. Marie was content to stay in Toronto, working in the hospital and hoping to get married at some point, but Adele wasn’t ready for that. She wanted more. Joining the Nursing Sisters as a qualified nurse was the only option for a Canadian woman wanting to serve overseas, and since officials had realized the demand for nurses would be far greater than what the Sisters could provide on their own, they had opened the application process to women who were not nuns. Her mother had pleaded with her not to go, but Adele had gently turned down every one of her arguments.

“I’m going for the country, Maman,” she said. “It’s my duty.”

It was only after she said she wanted to go to honour her father, who had died serving in the Boer War thirteen years earlier, that her mother admitted defeat. Guillaume, her mother’s second husband, and the man who had raised Marie and Adele as his own daughters, wholeheartedly approved of her plan, though his farewell hug felt tight with regret.

Out of the two thousand applications submitted that year, Adele was one of only seventy-five nurses chosen, and that was due to her exceptional nursing skills, citizenship, physical fitness, and high moral character. Maman couldn’t help but smile with teary pride the day Adele received her uniform. As soon as she put it on, anticipation had buzzed through Adele, all the way from the top of her stiff white veil to the hem of her official blue gown.

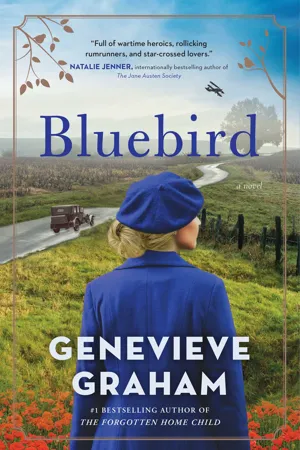

On the ship bound from Canada to England, Adele had met the three girls with whom she would soon be sharing a tent at a clearing station. Hazel and Lillian both hailed from New Brunswick, and Minnie was from Nova Scotia. What a relief to discover they were kindred spirits, and they all got along famously. As nurses, they would be in the war in the dual capacities of medical workers and caring women. They would be the first to greet wounded men coming off the trucks and trains from the Front, and their duties would include everything from cleaning and dressing wounds, dispensing medicine, delivering tetanus vaccines, and assisting in surgery and post-op care, to the often overlooked necessity of simply listening and comforting their patients. It wasn’t long before the soldiers came to affectionately call the nurses “Bluebirds” whenever they caught sight of their cheery blue uniforms.

Despite all her training, nothing could have prepared Adele for the front lines of war. It wasn’t just the horrible wounds from bullets, shrapnel, or fire. Men came in all conditions: delirious with trench fever they’d caught from hoards of lice, gasping for breath through pneumatic lungs, weak from dysentery, crippled by numb, gangrenous feet from living in fetid water with rats, and so much more. Adele had never imagined the horrors she would see, the gore she would handle, or the grief that would tear through her when another man died.

In her early moments of despair, Nurse Johnson, their steely-eyed matron, had drawn Adele aside and gently told her there was an art to staying sane here, day after day, month after month, year after year: stay busy and stay focused on medicine. Don’t get too close to the men on a personal level. But as much as Adele tried to think of the patients as statistics rather than scared and suffering men, she couldn’t. She became a mother bird, comforting them and caring, even if she knew some of them were fated to die under her watch.

Would she have come if she’d known the devastation that awaited her? She’d asked herself that question many times over the last three years, wondering if she was as courageous as her family claimed. Her answer was always yes. Unequivocally yes. Despite everything she’d seen and done, she’d come back here if she was needed. As much as Adele hated everything about this place, it was exactly where she was supposed to be, and that knowledge never failed to boost her from whatever dark place enveloped her. That, and the loyal camaraderie between her and her friends.

After peeling off her tired uniform, Adele folded back the rough grey blanket on her bed and crawled beneath its scratchy fibres, too tired to even contemplate writing in her journal. There was no comfortable spot on her lumpy pillow, but it didn’t matter. A rock would have been just as welcoming. As she closed her eyes, she felt the slightest bounce on her cot, then the velvet touch of her new friend nuzzling in around her neck like a hot water bottle. The General, they called him. The tiny black kitten with startling green eyes had followed Minnie to the tent a week before and now graciously permitted all the girls to give him attention when he wasn’t busy batting an imagined toy. Minnie might claim him as hers, but he made the perfect end to Adele’s day.

It seemed she had just dropped into sleep when the door to their barracks swung open.

“Everybody up!”

Adele’s eyes felt glued shut, but she forced them open. Beside her, Minnie grumbled something about it being only five o’clock, but Nurse Johnson marched in and started tugging blankets down. Lillian hadn’t even returned from the previous night’s shift yet.

“It’s all hands on deck this morning,” Nurse Johnson announced.

Booms rolled in the distance, closer and faster than mere hours before. Adele heard rain pattering against the canvas walls, then the sharp orders of men. The girls dressed quickly, grabbing their capes on the way out. As they sprinted to the hospital, heads ducked in the freezing rain, they passed two ambulances hitched to filthy, defeated horses. The wet animals swayed at the front of the wagons, their heads hanging low, their hooves partially submerged in icy mud. The nurses stood to the side as a long line of stretchers carrying wounded men snaked out the backs of the ambulances and into the clearing station.

All that day, ambulances ferried soldiers from the Front to the hospital. They arrived soaked and shivering from the wind and rain, broken and bleeding from enemy machine-gun fire or shells, some crying, some silent from shock. Adele heard snatches of conversation from those who were conscious, some claiming the Allies had won the battle, others merely shaking their heads with frustration and defeat. Adele rushed to triage them, supporting men who could walk to a bed, directing stretcher-bearers for those who could not. She unwound bloodied bandages, cleaned and treated wounds as best as she could while the men waited for a doctor, then she wrapped them up again. The hours blended together in a rancid swamp of blood, tears, and exhaustion.

“Excuse me, Sister?” a voice called.

Adele had just finished a difficult débridement, clearing necrotic tissue from a case of gas gangrene on the inside of a man’s thigh, and she turned toward the speaker as she removed her rubber gloves. He was tall and dark-haired, and the fibres of his uniform were stiff with dried mud and blood, but she could see no obvious wounds.

“Are you injured, Corporal…?”

“Bailey. John Bailey. No, Sister. It’s not me.” He pointed at a man on a cot across the tent. “You see the fella there at the very end? Is he all right? Will he be all right?”

“I’m sorry. I really don’t know. I haven’t had a chance to go to him.”

“He’s my brother,” he said quietly. “Please help him.”

She’d heard that before. He’s my brother. He’s my friend. Those beautiful, terrible words tore men apart and scarred her every time.

“Why don’t you go sit with him? I’ll be right there.”

“Thank you,” he said, then took off like a bull toward his brother.

Adele paused to give her patient with the gas gangrene a reassuring touch, but he barely moved in acknowledgement, then she went for a fresh pair of gloves, a bucket of water, and a clean cloth from the trolley before making her way to her new charge.

The chart at the end of the bed read Corporal Jeremiah Bailey, 1st Canadian Tunnelling Company. Facial lacerations, multiple fractured ribs. So these men were tunnellers. Members of the courageous breed who dug beneath the trenches, blocking and bombing the Germans. She’d never seen a tunneller before. ...