![]()

Part One

![]()

— 1 —

By the time they reached the Louvre, Bertie and Kate were nearly running. It wasn’t unusual for their walks to turn into unplanned races—both were in the habit of strolling a half step in front of people, and when they were together this could become a problem. First Bertie would move in front of Kate, then Kate would pick up her pace to match Bertie’s, and so on and so forth until they looked at each other and broke into a sprint. It had been that way since they were fifteen—that is, some fifteen years ago—and on ordinary days they both embraced it, competing to reach an imaginary finish line, celebrating whoever won. But today, despite wanting to arrive at the museum on time, their mutual fear of looking un-French was helping them to approach moderation.

At the end of the Rue de Rivoli, they slowed down and used each other as mirrors to readjust their outfits. A tug of the shirt when Kate lifted her eyebrow, and a twist of the skirt when Bertie sucked her teeth. The morning was hazy, with a fog that wasn’t quite willing to resolve into rain but was heavy enough to sit on the women’s hair and dampen their jackets. Kate reached into her bag for an actual mirror, which she used to apply a fresh layer of lipstick; they’d come to the museum at the invitation of a man Kate had met the night before in a bar, and she claimed not to have decided yet whether she wanted to impress him.

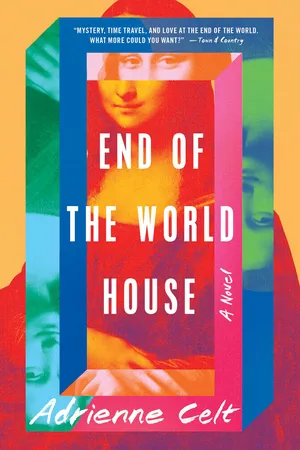

“What are your priorities, art-wise?” Bertie asked. She had a handkerchief around her neck, meant to look chic but also useful as a breathing filter when they passed through areas still smoky from the last round of bombs. The tracking app they had pored over on the plane attributed responsibility to a terrorist faction from the suburbs, who’d arrived via commuter rail wearing innocuous clothes and backpacks with gunpowder sewn into the lining. Now, Bertie shifted the knot of her handkerchief back to the side, into its more fashionable position. “Do you want to hear something dumb? I kind of want to see the Mona Lisa.”

“That’s not dumb,” said Kate. “Everyone wants to see the Mona Lisa.”

“I mean, that’s why it’s dumb. Usually it’s surrounded by a huge crowd, like, hundreds of tourists all crammed around this tiny painting which is probably only an okay painting, and which they only like because it’s famous.”

“So what, are you going to commune with it? Now that you’re the only one there?”

This had been the man’s offer, as they sipped their drinks and watched him glimmer lasciviously: private entrance into the museum, which today was technically closed. If she was honest with herself, Bertie had, in fact, gotten a shiver of pleasure from the idea. I deserve it, she’d thought. If not me, who? But she wasn’t about to be quite that honest with Kate, who would only make fun of her.

“Never mind,” she said. “We can skip it, I don’t care.”

“No,” said Kate. “We should see it. You’re right.” She snapped her lipstick shut and stowed it away again. “Do you really think people don’t like the Mona Lisa?”

Bertie shrugged. “I just don’t think most people have really thought about it.”

They’d come to Paris because the tickets were cheap. First there’d been a spate of hijackings, and then the bombings, and a period of general unrest. No one would call it a world war, but that was semantics. Now the borders were opening back up, under the auspices of a cease-fire, and though most Americans were still too nervous to travel, a few of the tourist boards were giving it the old college try. Kate and Bertie chose Paris because they felt that the French advertisements did the best job of flirting with the overall sense that the world was ending without ever actually stating outright that this might be your last chance for a vacation.

Also, Kate was moving in a month. So this was kind of a last hurrah. Bertie knew it would’ve been smarter to put her money and energy into finding a place in the city, finally moving out of the dismal Mountain View apartment she’d only rented to be near Kate, but that would’ve meant recognizing that Kate was really going to leave. So she’d suggested a trip instead. Anyway, the commute from San Francisco was hellish, more so now that the 101 was gone and the 280 was the only freeway option between the city and the South Bay. It was like God died, the day they shut the 101 for good. People actually cried in the streets.

In principle Bertie was a cartoonist, but for years now she’d made her money doing illustrations for a large tech company in Silicon Valley—one that liked to appear lighthearted and approachable to the public so they could sell more ads. Which worked surprisingly well. Even cynical people seemed reassured by the company’s palette of bright colors and its dinosaur avatar, which Bertie had now drawn in a thousand absurd situations, including on a rocket ship and driving a school bus, as well as learning “I think, therefore I am” from René Descartes with a book clutched in its tiny hands. The company paid Bertie more than she felt she was worth, so she drew it any way they wanted, as many times as they wanted, along with a rotating multicultural cast of nameless humans who accompanied the dinosaur on its adventures.

Bertie was supposed to be working on a graphic novel, too, on her own time, but these days she rarely had the energy. Not because of her job so much as the malaise that lay over everything. Politics, global war, world hunger, just—everything. Kate had wanted to be an essayist, but that was years ago: she gave it up in favor of directing publicity and fundraising for a nonprofit that lobbied to improve the quality of school lunches. It was theoretically a more selfless career than Bertie’s, but Bertie didn’t see it that way. After all, Kate liked being in charge; she liked the power. Whereas Bertie was indifferent to her job, which sometimes made her feel like she had less self than anyone. At least if she’d hated it, she could’ve quit, but no one wanted to hear you complain about leaving your okay job with good health insurance—not at a time when the U.S. suddenly had honest-to-God refugees streaming towards the coasts from the South and the Midwest, finding not much in the way of aid or sympathy. So she kept going every day, sometimes enjoying herself, sometimes spending whole afternoons reading the comment threads at the end of online advice columns, letting rage and disappointment wash all over her in order to reach the rare and blissful moments of catharsis.

That morning the crowd around the glass pyramid in the Cour Napoléon was sparse, just a few tourists taking photographs of the grounds and some Parisians passing through on their way to work. Near the fountain, a mother and her small daughter threw pieces of croissant to the birds, and a few yards behind them a group of four people was peering at something at the top of a tower, shielding their eyes with their hands. A few days before, when Bertie and Kate had walked by the same courtyard while heading to the Tuileries Garden, the space had been packed, including a line of museum-goers that snaked back half a block, but since the Louvre was closed today, most people had made other plans. The man from the night before had told them he had connections and could get them in for a private viewing if they showed up by eight-forty-five in the morning and gave his name—Javier—at the entrance. It sounded like a delicious secret, almost too good to be true. They’d found Javier at a jazz club somewhere in the Fifth Arrondissement, an old place stuck in a cellar which boasted a surprisingly good band and a crowd of middle-aged Frenchmen who were eager to dance with youths from abroad and buy them red wine for five euros a glass.

The mist finally turned into a drizzle, and Kate took Bertie’s hand.

“Oh, hi,” said Bertie, and in answer Kate gave her hand a squeeze, the same gentle greeting they’d shared for years, but now at a castle, in Paris, in a light Parisian rain. They stood there for a second, admiring the cornices and balustrades, the judgmental statues and the omnipresent pigeons. Bertie thought it was impressive that so many pigeons remained in the city when the songbird species were all in decline, but then again pigeons were willing to eat garbage, so perhaps they were more fit to survive. Later she would remember that the air in the courtyard smelled tinny, and that the crowd had gotten denser while they stood around. But in the moment she only felt happy to be there, slightly damp and still somewhat young, side by side with her best friend.

“Okay, are you ready?” Kate asked.

“What do you—?” Bertie started to reply, but before she could finish, Kate took off running towards the entrance, still holding her hand and almost pulling her arm from the socket.

“Jesus!” Bertie laughed as they whipped through a cluster of suit-and-tie pedestrians, earning several dirty looks. One man snarled as Bertie’s shoulder slammed into his. “Sorry!” she called back to him, but he didn’t seem to accept the apology, and muttered something under his breath as he turned away. On the other end of the courtyard, a different, younger man paused to watch the spectacle of them before turning to the side and wiping a drop of rain away from his forehead. He had no coat, and his hands were stuck in his jeans pockets against the morning chill. A round face. Later, Bertie would remember him, too, but it would take her some time to think why.

Kate stopped outside the pyramid doors and checked the time on her phone; neither woman had bothered to activate international service, so they couldn’t call anyone or do anything outside the warm glow of the hotel Wi-Fi. But neither one owned a watch or a camera, either, so they still carried their phones wherever they went.

Now that she was over whatever momentary ebullience had made her start sprinting, Kate pulled herself together fast. Her face bright without being sweaty, her hair preternaturally smooth. She tugged on the door, but it was locked.

“It’s only eight-thirty,” she said. “What do you think we should do?”

“He’s your loverboy,” Bertie replied. She hadn’t found Javier particularly appealing, with his shiny face and his subpar teeth, but Kate always made friends with everyone. “Didn’t you get his number?”

“Hell no. Anyway, we weren’t supposed to meet him until later. And,” she held up her phone, “no service, remember?”

Around them, people were starting to stare. A few—other tourists, most likely—seemed interested, perhaps hoping that Bertie and Kate’s presence indicated the museum might be opening after all. But the others looked obscurely angry.

Bertie shifted uncomfortably from one foot to the other. She had the sudden premonition that they wouldn’t get in; that it was all a joke. Why had they believed a total stranger when he said he could do them such an enormous favor? Javier was probably off laughing somewhere, telling his friends the story of the stupid American women he’d met at a bar.

“Let’s get out of here,” she said, pulling on Kate’s sleeve. “We can do something else today. It doesn’t matter.”

But Kate shook her off, and muttered, “Ugh, let me be.” She had never liked being managed. It used to be a problem for her at work, though she’d long since jettisoned the issue into her personal life. Bertie backed away, trying not to be hurt, and turned to meet the eye of the young guy she’d noticed watching them earlier. His eyebrows lifted in surprise.

“Oh, wait,” Kate said. “Now I remember.” Without further explanation, she knocked three times on the glass, then twice, then three times again. From the dim back of a hallway at the bottom of the grand pyramid stairs, someone came into view. She looked like a security guard or a docent, in a dark fitted suit with a walkie-talkie on the front. The woman made a big production of unlocking the doors and then opening them just a sliver, sticking her head outside into the mist. “Qui sont vous?” she asked, and when both Bertie and Kate hesitated before trying to reply, she clicked her tongue in exasperation and switched to English. “You are… who?”

Kate frowned. “We’re with Javier?” she suggested, as if not quite certain herself. But the security guard’s whole demeanor changed.

“Oh. You come, then.” She stepped back, holding the door to allow them inside, and both women slipped past her. A father and his teenage son, appearing from nowhere, tried to follow them in, but the guard waved her hand at them and said, “Shoo!” before closing the glass door and locking it. Bertie felt a quick wave of claustrophobia as the lock clicked into place, but it was soon overwhelmed by the immensity of the museum in front of them, and the grandeur. Sometimes good things happen, she thought, looking over her shoulder at the father and son who were frowning on the other side of the door. By the time she turned, the guard was bustling away down the hall, disappearing around a corner, and leaving Kate and Bertie alone. They looked at each other. “Okay, then,” Bertie said.

When Bertie had to explain Kate to people who didn’t know her, she sometimes called her “my bitchy friend Kate,” even though it made her feel guilty afterwards; Kate was really more particular than bitchy, but that seemed like splitting hairs. The funny thing was, at a bar or a party Kate would be nice to anyone, even creeps like Javier. She built up lines of devoted followers who pointed her out to one another in a fond, “Have you met…?” kind of way, and she was popular at the office, too, as Bertie had seen on afternoons when she came to pick Kate up after work. She made jokes and remembered people’s birthdays; when everyone wanted to go to happy hour, she was often the first to say yes, and therefore the one elected to mother-hen everyone to a single location. But when it came to actual closeness, real affection, she could turn off her internal lights in an instant.

Bertie had experienced this firsthand back in high school, when Kate moved to her school district in the ninth grade—Kate’s third school in as many years, since her stepdad kept getting relocated for work—and they spent a whole year skirting around one another, sticking to their separate social universes. Kate had purple hair back then, and Bertie naturally assumed that Kate was too cool for her, a sentiment Kate evidently shared for a number of months. Bertie hung out in the art room, which Kate did not, and Kate went to underground all-ages punk shows, which Bertie emphatically did not. The one time she’d tried to talk to her in those early days, Bertie had gotten out maybe one sentence about theatre auditions before she noticed Kate’s eyes traveling down her body, taking in her loose curls and the cheap cotton skirt she’d bought at a folk festival, which had until that moment made her feel both international and elegant. Later Kate would explain that she wasn’t being dismissive of Bertie so much as hippies in general, because Seattle had so many that they threatened to absorb you, like water into the spongy ground. But at the time, Bertie saw the look on Kate’s face, and simply shut her mouth and walked away.

“Wait, what?” Kate had called out after her, but Bertie hadn’t bothered to reply.

The change came in tenth grade, when they were seated at adjacent desks for the PSATs. Everyone taking the test had to show up at school on a Saturday morning, and people were full of test-day jitters, which only got worse when the administrators split them up alphabetically and pl...