eBook - ePub

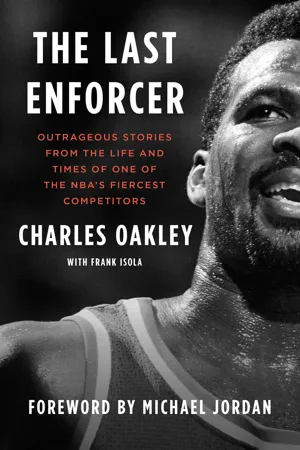

The Last Enforcer

Outrageous Stories From the Life and Times of One of the NBA's Fiercest Competitors

- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Last Enforcer

Outrageous Stories From the Life and Times of One of the NBA's Fiercest Competitors

About this book

In this “incredible read on some incredible days and nights in the old association” (Adrian Wojnarowski, ESPN senior NBA insider) Charles Oakley—one of the toughest and most loyal players in NBA history—tells his unfiltered stories about his basketball journey and his relationships with Michael Jordan, LeBron James, Charles Barkley, Patrick Ewing, Phil Jackson, Pat Riley, James Dolan, Donald Trump, George Floyd, and many others.

If you ask a New York Knicks fan about Charles Oakley, you better prepare to hear the love and a favorite story or two. But his individual stats weren’t remarkable, and while he helped power the Knicks to ten consecutive playoffs, he never won a championship. So why does he hold such a special place in the minds, hearts, and memories of NBA players and fans?

Because over the course of nineteen years in the league, Oakley was at the center of more unbelievable encounters than Forrest Gump, and nearly as many fights as Mike Tyson. He was the friend you wish you had, and the enemy you wish you’d never made. If any opposing player was crazy enough to start a fight with him, or God forbid one of his teammates, Oakley would end it.

“I can’t remember every rebound I grabbed but I do have a story—the true story—of just about every punch and slap on my resume,” he says.

In The Last Enforcer, Oakley shares one incredible story after the next—all in his signature “unflinchingly tough, honest, and ultimately endearing” (Harvey Araton, New York Times bestselling author) style—about his life in the paint and beyond, fighting for rebounds and respect. You’ll look back on the era of the 1990s NBA, when tough guys with rugged attitudes, unflinching loyalty, and hard-nosed work ethics were just as important as three-point sharpshooters. You’ll feel like you were on the court, in the room, can’t believe what you just saw, and need to tell everyone you know about it.

If you ask a New York Knicks fan about Charles Oakley, you better prepare to hear the love and a favorite story or two. But his individual stats weren’t remarkable, and while he helped power the Knicks to ten consecutive playoffs, he never won a championship. So why does he hold such a special place in the minds, hearts, and memories of NBA players and fans?

Because over the course of nineteen years in the league, Oakley was at the center of more unbelievable encounters than Forrest Gump, and nearly as many fights as Mike Tyson. He was the friend you wish you had, and the enemy you wish you’d never made. If any opposing player was crazy enough to start a fight with him, or God forbid one of his teammates, Oakley would end it.

“I can’t remember every rebound I grabbed but I do have a story—the true story—of just about every punch and slap on my resume,” he says.

In The Last Enforcer, Oakley shares one incredible story after the next—all in his signature “unflinchingly tough, honest, and ultimately endearing” (Harvey Araton, New York Times bestselling author) style—about his life in the paint and beyond, fighting for rebounds and respect. You’ll look back on the era of the 1990s NBA, when tough guys with rugged attitudes, unflinching loyalty, and hard-nosed work ethics were just as important as three-point sharpshooters. You’ll feel like you were on the court, in the room, can’t believe what you just saw, and need to tell everyone you know about it.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Last Enforcer by Charles Oakley,Frank Isola,Frank Isola in PDF and/or ePUB format. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

eBook ISBN

9781982175665Subtopic

Social Science Biographies1 KNOCKING OUT A JACKASS

I did not punch Charles Barkley.

Do you need me to repeat that? I will if it means people will stop spreading lies about me. Enough is enough. I’m going to set the record straight because for more than twenty years, that rumor—the one of me allegedly punching Barkley before an important NBA Players Association meeting in 1999—has been told over and over, to the point that it’s become something of an urban legend. But the story is false. So for the last time, I did not punch Charles Barkley.

I did, however, slap the shit out of him.

Barkley had it coming to him. He was talking a lot of shit about me. That’s what he does. He talks too much. So I did what I do. Mention my name to Barkley today and he’ll still go the other way.

You get hit with a lot of words in the league. You get hit with a lot of elbows, forearms, shoulders, and occasionally fists, too. You don’t have to hit first, you just have to make sure you get in the best shot. And I got Barkley pretty good.

I was a power forward in the NBA for nearly two decades with the Chicago Bulls, New York Knicks, Toronto Raptors, Washington Wizards, and Houston Rockets, and I had plenty of run-ins over those years. I played in the golden era of physical play, the 1980s and ’90s, and combat was part of my job description. According to the record books, I had almost as many rebounds (12,205) as points (12,417), which tells you what my role was on every team. That’s a lot of work in the paint, and that’s where things tend to get nasty. There’s one more telling statistic: I rank fourth all time for personal fouls (4,421), just behind Robert Parish, Karl Malone, and Kareem Abdul-Jabbar. I’d like to think that most of the fouls were worth it. A lot were used to prevent a dunk or a layup. In New York, Pat Riley got credit for saying we had a “no layup rule.”

I played by that rule my whole life.

In addition to Barkley, I mixed it up with Xavier McDaniel, Rick Mahorn, Bill Laimbeer, Alonzo Mourning, and even Larry Johnson, who later became my teammate with the New York Knicks. When you really think about it, that’s not so many fights over the course of nineteen seasons. Most of the violence in the eighties and nineties NBA was controlled, and contrary to popular belief, I didn’t fight all the time. I fought when I needed to. I fought when it mattered. Was I a physical player? Absolutely. Dirty? No. But if you fucked with me or one of my teammates, I wasn’t going to back down. Never. I’ve been that way my entire life, and I’ll be that way until the day I die.

I wasn’t the first guy in the NBA who was wired like that, but I might have been the last. Before me, there were bruisers like Maurice Lucas, Lonnie Shelton, and Kermit Washington. A few months after the Portland Trail Blazers won their one and only title, Lucas was featured on the cover of Sports Illustrated. It was the magazine’s NBA season preview issue, and the photo was of Lucas positioning himself for a rebound by sticking his elbow in the throat of the Seattle SuperSonics’ Dennis Johnson. The headline was “The Enforcers.”

I liked that, “Enforcer.” That nickname stuck with Lucas and it made an impression on me. I was the guy who would do all the little things to help my team win: rebound, defend, and be physical. That was my mentality in every game.

In one of my final seasons with the Knicks, we played in Portland, and Mo Lucas came into our locker room to talk to me after the game. We had a nice conversation. He said he admired the way that I went about my business. The guy was a legend. He died of bladder cancer in 2010 at the age of fifty-eight, one year older than I am as I write this. I think about that a lot.

I think about a lot of things that happened during my career. I think about getting traded by the Bulls before they won the first of their six NBA Championships over eight seasons. Or losing to the Houston Rockets in the 1994 NBA Finals after taking a 3–2 series lead with the Knicks. The Knicks traded me prior to the 1998–99 season, and they went back to the NBA Finals that year, though they were beaten by the San Antonio Spurs, who were led by David Robinson and a young Tim Duncan.

That Knicks trade wasn’t the last time the organization threw me aside. All those years of taking a charge and landing on my back or jumping into the front row for a loose ball didn’t mean anything twenty years later to the guy then running the franchise. They dragged my ass out of Madison Square Garden.

They started that fight, not me. But that’s true of all the fights I’ve had. Someone starts it, I end it.

Because I fight like a man.

That’s the way I was raised.

Cleveland, Ohio, is my hometown. It’s a tough and proud city. I grew up on East 123rd Street and Superior. It was a nice house with a front porch. The neighborhood was mostly Black; probably 95 percent Black and we all looked out for one another. That’s just how it was.

Right down the street, there was a barbershop where the older guys would shoot dice and play cards. When I was about ten or eleven years old, I’d clean up the place and they’d give me money. They’d send me to the store to buy them food. They’d throw me a $20 bill and I’d keep the change. When I was a few years older, they’d let me roll dice and play cards with them. It was a good hustle—when I won.

In the neighborhood you had the barbershop, Laundromat, record store, seafood place, food market, and a corner store with a barbecue counter where they made the famous Polish Boys. That’s a sausage sandwich with kielbasa on a bun. You cover it with French fries, coleslaw, and barbecue sauce. The Polish Boy is big in Cleveland. We invented the thing, and this place in my neighborhood had the best barbecue sauce going.

I used the money from the barbershop and the dice games to buy food. I never told my mother, Corine, that I got the money from gambling, because I didn’t want to get in trouble. I wasn’t sneaky, I was smart. My mother wouldn’t have been happy about me playing cards with the old guys, but she was okay with me playing cards with her. That was fine. We’d play poker or Tonk, a card game that was popular among blues and jazz musicians from the South going all the way back to the 1930s. You can play with either two or four players, so me and my mom would play a lot. My mom was good. She’d talk a lot of smack when she played, but she kept it together. She never drank or smoked. That wasn’t her thing. She worked in a bar for fifteen years and never drank. My mom still lives in Cleveland, and we’re still very close. I’m there all the time.

I didn’t know my dad much. My father, Charles Oakley II, came from a big family; he was one of ten kids, and when I was growing up, they owned five gas stations in Cleveland. He was always working. He lived with his brothers, while my siblings and I lived with our mother. I seen him, but I didn’t see him a lot, you know what I mean? Then he died of a heart attack in 1971. He was only thirty-five and I was nine. It’s just one of those things.

I grew up the youngest of six children, with one brother, Curtis (eleven years older than me), and four sisters: Saralene (seven years older), Carolyn (five years older), Diane (three years older), and Yvonne, who is twelve years older than me, but Yvonne lived in York, Alabama, with our grandparents on our mom’s side. I’m sure you’ve never heard of York. It’s in Sumter County, close to Mississippi. It’s about a two-hour drive northwest to Birmingham and about a five-hour drive to Atlanta. I can make it in four.

According to the local records, the town was established in the early 1830s. It was a farming and cotton town, and during the Civil War, the railroad passed through York on its way to a military hospital in Meridian, Mississippi. After World War II, the train traffic slowed down and people started to move out. It’s a mostly Black town, and yet the first African-American mayor wasn’t elected until 1996. Progress, like life in general, moves slowly in York. But I still love it there.

When I was seven years old and in the second grade, my sister Diane and I moved to York to live with our maternal grandparents, Julius and Florence Moss, and join Yvonne. Curtis, Saralene, and Carolyn stayed behind in Cleveland with my mother. My mom was trying to get established. She was living in an apartment and needed more money to buy a house, so it was easier for her to send the two youngest kids to Alabama for a few years.

It wasn’t bad in York. My mother would visit three times a year, and in the summer she would stay for a few weeks. I was fine with it because I had a lot of cousins in Alabama and I was spending a lot of time with them—my dad’s side of the family was from there, too. Out of maybe one thousand people in York alone, I was probably related to three hundred of them. It was like being away at camp year-round. We all protected each other.

That doesn’t mean it was all fun and games. I did go to school. Education was important to my family. A lot of the people in my family worked in the school system, either as teachers or administrators, and a few of my aunts attended the University of Western Alabama. We didn’t mess around when it came to school. Or church.

My grandfather Julius was a deacon, so every Sunday we were in church. He’d make a few trips in his car on Sunday morning for those of us who needed a ride. You didn’t have a choice. My grandfather baptized me in the pond down the street. He walked into the pond with his boots on, tilted my head back, and that was it.

I learned at an early age that my parents and grandparents would not tolerate any bullshit. If I talked back or, God forbid, used profanity, I was in trouble. My grandparents would lay me across their laps and give me the beating of my life. The only voices you heard in that house were my grandparents and the television. And the TV went off every night at nine o’clock, so it got quiet early there. There wasn’t a lot of nonsense going on.

Julius Moss was a special man. He was born in Alabama in 1906, so you can imagine how life was for him. Growing up in the Jim Crow South, my grandfather saw it all. Shit, by the time he was twenty-five, he had probably seen more than he wanted to see. But he was a proud man, with an incredible work ethic that was second to none. On top of being a deacon in the church, he was a blacksmith, a farmer, and a coal miner. He hunted deer. He built his own house, starting with three rooms and eventually adding on four more. He slept four or five hours every night and never complained.

My grandfather was tough. His hands were so rough and covered with calluses that he could pick up a piece of hot coal. He was six-foot-three and strong. When I was a kid, my uncles would tell a story about the time my grandfather knocked a mule out. One day he was in the field and the mule didn’t want to work. He was pushing and prodding, and I guess the mule got real aggressive. It was either my grandfather or the mule, so he knocked the mule out. Is the story true? I don’t know. Like I said, my grandfather was tough. I’d pick him over the mule. I’ve knocked out a few jackasses in my life as well.

We’d all help my grandfather with his farming—he’d have us out in the field picking cucumbers and tomatoes to feed the family. In the summer, we’d help him with a side job that he had, going to a big farm up the road to feed their many horses and cows. It was a farm owned by white people, and it had a big white fence around it. Ain’t no Black people with a farm that big with a white fence around it. My grandfather had some horses of his own, about six or seven cows, and one bull. He wasn’t big-time. He just did what he could.

He passed away when I was in my second year in the NBA. Julius Moss wasn’t big into sports, so the fact that I made the league didn’t mean a lot to him. But I know he was proud. He was happy I had a job and was earning an honest living.

My father passed away while I was living with my grandparents. When I think about it now, he died so young. The funeral was in Alabama, and it was big; there were a lot of people there, family and friends, and they were all crying. I was only nine, so I didn’t really process everything that was happening.

I spent four years in Alabama before my mom came to take me and Diane back to Cleveland. When she said I had to leave, I hid under the bed. I didn’t want to go back. I was having a good time with my cousins. We were playing football and basketball all the time. Why would I want to leave? But my mom had gotten herself established in Cleveland, as she’d been working to do, and had bought a house. So it was time to move on.

Those years in Alabama helped me become the man and player I turned into. Because of my grandfather’s example, I never bitched about basketball practice or playing back-to-backs. I never made excuses. I practiced and played hard every day, and even when I wasn’t at my best I didn’t quit. I treated basketball as my job. It could be difficult, but I’d seen what real work looked like.

I was developing that attitude already when I moved back to Cleveland and started playing basketball at a local YMCA every Sunday. By the time I was thirteen, I was playing against guys who were sometimes four and five years older than me. There were a lot of old-school guys who would try to take your head off when you went to the basket. I decided that my attitude would be to stand tall and tough. If they’re going to give it to you, you got to give it to them. I wouldn’t fight for no reason, but if somebody crossed me, insulted me, or attacked me, then we’d have a problem.

The first time I really had to put that theory into practice on a basketball court was with this one guy at the games who knew karate, and made sure that everybody was aware of that. For a long while, he gave me a hard time. Everyone else at the games knew he was testing me. They were wondering if and when I was going to respond. Well, one day he tried to get me and I went after him. All that karate didn’t help him, because once I threw my hands up, there was nothing he could do.

I played a lot of football in the street as a kid. When you grow up playing on concrete and in a lot of cold weather, you either get tough quickly or you do something else, like watch a lot of television. I was big and strong even as a kid, so football seemed like the natural sport for me. A lot of kids in Ohio dream of playing for Ohio State, but I didn’t really focus on that. I figured if I’m good enough, someone will find me. Learning to play football helped me with basketball because you learn how to take a hit and give a hit.

When you’re playing football in that setting and you got guys talking shit, there’s going to be some minor fights. Nothing big. The next day you get over it and you go back to playing. But there was one time when I was playing organized peewee football and that rule didn’t hold. It was ugly. There were these twin brothers from the neighborhood who were getting mad at me because I was whoopin’ their asses in practice. I was probably twelve or thirteen. One day after practice, the twins and their uncle, who was probably nineteen, jumped me. They got me pretty good. In fact, they broke my arm. When I got home, I told my mother I got hurt in practice. I didn’t tell her anything about getting jumped because I decided that wasn’t going to change anything. I had to fight for myself. My mother shouldn’t have to do that. I wasn’t mad. I wasn’t scared. My thing was I needed to do a better job of protecting myself.

Years later, when I was in the NBA, I returned to Cleveland during the off-season, and I saw the twins’ uncle sitting at a bus stop. I was with some friends who knew the story and wanted to scare the guy. I told them, “Leave him alone,” and I walked into the restaurant we were going to. Did my friends listen? It doesn’t seem that way—all I know is, he didn’t catch that bus that day. I see the twins every now and then, and they both keep their distance. That’s a smart move.

If my toughness and work ethic came from my grandfather, then my love of cooking came from my mother. My mom is a great cook. She makes incredible ham hocks, chitlins and collard greens, string beans, and pound cake and sweet potato pie for dessert. All my aunts can cook, too. When I was growing up, they would cook and I would ask questions about the meal. I never cooked when I was a kid, but I watched and learned from them, and once I got into the league I started cooking. When we were on the road, you’d eat either room service or go to a restaurant. I always thought the food was bland. So when I got home, I wanted to eat healthy and make things the way I liked to make them. And whenever we played games in Cleveland, my mom would cook for the whole team. She would make smoked turkey for Patrick Ewing because Pat didn’t like pork. One downside of all that good food is that I ended up being picky and demanding about the quality of what I eat. People hate to go out to eat with me because they know there’s a good chance I’m going to send the meal back.

My high school in Cleveland was called John Hay. Not John Jay (a mistake a lot of people make). It’s John Hay High School. A few years ago the city honored me with a street sign—Charles Oakley Way—in front of my alma mater. But back when I was a student, I was just another kid trying to figure things out. Shit, just getting to school was a job: I had to take two buses to get there. Not school buses—public transportation. I would either take the No. 6 to the No. 3 or the No. 10 to the No. 40. The other option was to walk two and a half miles. If we had lived a few houses down, I would have been in another school district that had actual school buses. The crazy thing is, when people see you on a school bus, they look at you as a student. When they see you on a public bus, they start wondering if you’re skipping school and if you’re up to no good, especially if you’re a Black kid.

There was one day, I was probably fifteen years old, and after waiting a long time for the second bus, I decided to start walking home. I walked past the Green Door, which was a bar where guys sold a lot of weed. All of a sudden a car pulled up; two undercover cops got out and threw me against the wall. In the neighborhood we called these two cops “Starsky and Hutch.” They drove around in unmarked cars and harassed people in the hood. They accused me of selling drugs. I didn’t have anything on me, so they threw me in the car and drove me around for three hours. What the fuck did I do?

They told me, “We’re going let everyone see you, an...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Foreword

- Chapter 1: Knocking Out a Jackass

- Chapter 2: Welcome to the League

- Chapter 3: Basketball Junkie

- Chapter 4: Protecting MJ

- Chapter 5: The Bomb Squad

- Chapter 6: The Price of Being Late

- Chapter 7: Life with Riley

- Chapter 8: High-Stakes Basketball

- Chapter 9: Reno to Houston

- Chapter 10: “They Will Choke”

- Chapter 11: Going Hollywood

- Chapter 12: New York Time’s Up

- Chapter 13: Barkley and His Big Mouth

- Chapter 14: Five Minutes for Fighting

- Chapter 15: The Reason They Called Me Oak Tree

- Chapter 16: The Last Waltz

- Chapter 17: Two Kings

- Chapter 18: The Owner

- Chapter 19: Say His Name

- Chapter 20: The Blood of a Legend

- Acknowledgments

- About the Authors

- Index

- Copyright