![]()

On March 13, 2010, driving at night in a thunderstorm, my mother got stuck on a flooded road near the Hackensack River. Her car stalled out and the electrical system failed, so pressing on the horn yielded no sound. She didn’t have her cell phone with her. The river forced its way inside the car, covering her ankles, moving up to her knees. She was eighty-five years old and in poor health and she knew that if she left the car she’d be dragged down into the water. She was sure she was going to die.

I was living with my family in Westchester. The rain had been crazy all day. In the morning I’d promised my kids that we’d go out to the toy store and the library, but although we wouldn’t have to travel more than half a mile, the storm was so wild that I wasn’t sure about leaving the house at all. Heather was at a conference that weekend, and I had the kids on my own. Finally I told myself it couldn’t be so terrible to drive a few blocks, and I took them to the toy store. Driving there turned out to be an exercise in not letting them see how frightened I was—I could barely make out the road—and after they’d each picked a toy, I decided to skip the library and take them back home.

My niece, who was in high school, was giving a dance recital that night, but the drive took an hour in good conditions and would have been a nightmare during a storm like this. I wrote to my sister, Melinda, with apologies; she told me it was fine, and added that our mother was still planning to attend.

I can’t say I was surprised. My mother was like a child in many ways. She’d never been good at knowing her own limitations or thinking ahead. One of my early memories was of an evening when she took Melinda and me to see our grandparents off at Penn Station after they’d visited us in New Jersey. I was four and my sister was seven. Our grandparents were taking a train back to Pittsburgh. She felt it important to help them find their seats, though they were only in their early sixties and were perfectly capable of doing this themselves, and she felt it important to stay with them, soaking up every minute of togetherness, even after the announcement that anyone without a ticket had to leave the train. She told my sister and me to get off and wait for her on the platform. I don’t know what made her want to postpone leaving until the last possible moment. I don’t think there was any real reason; I think it was just hard for her to leave. That was one of the first things you got to know about my mother, if you knew her at all. It was hard for her to let anybody go.

My sister and I waited outside the train. We heard a second announcement, and then a third, and then we saw the train start to move.

I don’t remember what I was thinking. I don’t remember if my sister said anything. But I do remember that the train began moving and my mother wasn’t with us and I didn’t know what we were going to do.

Finally she emerged in the space between two cars. She looked at us, smiled nervously, looked down at the swiftly moving platform, and jumped.

My mother, it should be mentioned here, was not a graceful woman. She’d never been athletic, and a providential moment of nimbleness was not bestowed upon her now. She leapt from the train in an odd way—the position of her body reminded me of an angel in a cartoon, reclining on a cloud while playing a harp—and landed heavily on the platform, and cried out in pain.

At the distance of sixty years, I can see that she was lucky. The force of the fall was taken by the fleshiest part of her body. She didn’t break any bones. She didn’t hit her head. She didn’t suffer any serious injuries. But for months she bore a frightening bruise, covering most of her thigh and part of her backside. (She showed it to us more than once, even though, for me at least, once was more than enough. She might have thought it was educational for us in some way.)

To my four-year-old mind, this adventure seemed to say two things about her. Her leap and her bruise seemed to mark her as both heroic and unbalanced. I can’t deny that I thought there was something glorious about the sight of her leaping from the train, but neither can I deny that I understood, even then, that there was something off about it too, something that set her apart from other grown-ups, and not in a good way.

All of which is to say that in 2010, when I learned my mother was planning to attend the recital, it didn’t even occur to me to try to talk her out of it. I thought it was foolish, but I also thought it was just her, and I’d learned long ago that when I tried to talk her out of doing something she was intent on, I had no chance.

I did whatever I did with the kids that night. I imagine I made them some nutritionally questionable dinner—chicken fingers for Emmett, mac and cheese for Gabe—and watched a movie with them and waited eagerly for them to fall asleep. After that I’m sure I either wrote or wasted time on the internet. The storm didn’t die down. If you care to look it up, just search for “storm” and “March 13, 2010” and “New Jersey.” I remember that I thought about my mother once or twice, wondering how she’d fared in the miserable weather. I wrote her an email at around midnight, and was surprised when I didn’t hear back—she liked to stay up late, and she was always on her computer—but I have to admit I didn’t think about it very much. I assumed things had turned out fine.

In the morning I checked my email and saw that she’d written to me at two. She told me what had happened—she’d finally been found by the police as they patrolled the flooded streets—and said that it had been the worst night of her life.

A few days later, Melinda visited her and noticed that her balance was off. She took her to her doctor, who sent them to Englewood Hospital to determine whether she’d had a stroke.

I met them at the hospital. My mother had already had a few tests and they were waiting for results. She was sitting in one of those backless gowns, which seem designed to humiliate you and thereby render you willing to do what you’re told. She was normally an irrepressibly chatty person, but now she was sitting on the examining room table with a doleful expression, not saying a word. Occasionally she swung her legs in the air, looking like a disappointed child.

When she did speak, it was hard to tell if she was slurring her words. If you listen carefully to anyone at all and ask yourself whether they’re slurring their words a little, it can be hard to be sure.

I was worrying about many things.

I was worrying about her, of course. I was worrying about how much damage she might have suffered; I was worried about whether she was going to be able to continue living on her own. But I was also worrying about myself. I had successfully kept her at arm’s length for many years, not really doing much for her except having dinner with her from time to time, and this was comfortable for me. Now it seemed that I might have to call on different capacities in myself, and I didn’t want to.

![]()

You find out who you are at funerals. You find out who you are, I mean, at the funerals of old friends, because the families of the one who died, their inhibitions loosened by their grief, will speak to you in an unguarded way, and sometimes they’ll tell you things about yourself that they wouldn’t have told you otherwise.

In the months before my mother’s stroke, I’d attended the funerals of two old friends. When I went to Seth Kaplan’s funeral and expressed my condolences to his sister, she, for some reason, launched into a long account of her memories of me from back in junior high school, which, it turned out, weren’t memories of me at all. They were memories of my mother.

“All I can remember is these phone calls from your mother,” she said. “It’d be dinnertime on a weekday night and your mother would call, hysterical. ‘Is Brian there? I can’t find Brian. I’ve been calling everywhere. I’ve called the hospitals, I’ve called the police.’ And it would only be six o’clock. I didn’t get it. ‘Is Brian there?’ ”

At Robert Gordon’s funeral, Robert’s mother said much the same thing. “She was always calling. She was always frantic. I used to wonder how you could put up with it. I could barely put up with it.”

When you’re young, it’s hard to see your parents in context. Your parents are the context. Your parents are the people who’ve mapped the world for you, and it can take years to discover that their maps are imperfect or incomplete. You think they’re teaching you about how a person should be; it takes a long time to understand that they’re merely teaching you about how they want you to be.

It took me years, even decades, to fashion a relationship with my mother in which I could affirm my love for her while placing limits on her. And now, in the hospital room, as she sat on the examining table and swung her legs childishly, at the same time as I was worried for her, I was thinking with dread that I was probably going to have to let her much more consistently into my life.

She said she wanted a soda, so I walked down the hall to a bank of vending machines. When I started back toward the room, my mother wasn’t in my line of sight. I could only see my sister. She was looking out the window in a meditative silence.

When we were young, my sister had been my leader, my ideal co-conspirator, my guide. In recent years she’d endured a lacerating illness and a grueling treatment regimen. She was working six days a week at a demanding job. I knew she’d be willing to do most of the work of caring for our mother; I knew it would be wrong to let her.

I gave my mother the soda.

“Where do you want to have dinner?” she said. “You’re staying around for dinner, right?”

![]()

How can you see your parents clearly? How can you see them as they are?

Sometimes you’ll notice a middle-aged son or daughter reacting to a very old parent with an outsized irritability—rolling their eyeballs and sighing at whatever the parent says. It’s as if the parent’s mere presence has sent the child tumbling through time, all the way back to middle school. How can you make sure you’re not that son or daughter?

I’m wondering about these questions because I’ve written about my mother before, and I don’t think I even came close to getting it right.

Decades ago, after my father died, I wrote a novel that began simply as an attempt to put my memories of him on paper. My mother was in the novel too, of course. But I don’t think I treated her fairly.

The portrait of my father was bathed in the glow of idealization. It’s easier to idealize the parent who’s dead. It’s easier, also, to idealize the parent who was ever-distant than the parent who never knew when to leave.

And it’s easier to satirize your voluble Jewish mother than your moody Irish father. This is one of the basic laws of fiction.

I didn’t show it to her when I was working on it, because I knew that what I wrote about her would hurt her, and I didn’t see the point of going out of my way to hurt her by showing her a novel that might end up in a drawer. (This was back in the days of typewriters, when unpublished novels really did end up in drawers.)

When it was finally accepted for publication, I gave her a copy. I handed the box of xeroxed pages to her after she came into the city to meet me for dinner one night. I can’t remember if I said anything to try to prepare her.

The next morning, I got a message on my answering machine.

“Brian? This is your former mother…”

There were some things she said I absolutely had to take out—“I won’t be able to face people in Teaneck, the way you wrote about me”—and I did what she asked. But taking out the more egregious details didn’t help much, since she found the portrait as a whole so wounding.

After the novel, which was called The Dylanist, was published, I told a couple of friends that I felt guilty about having hurt her, and both of them said that it’s in the portrait of the mother that the novel’s warmth and life reside. The father is like a mythical figure; the mother is real.

But I don’t think she ever came to see it that way. I know she looked at the novel often during the thirty years in which she outlived him, because rereading the parts about my father made her feel closer to him, but it must have been painful to go back to the book for that sense of connection and to keep coming across descriptions of herself that she found embarrassing. I don’t think it occurred to me that I had much of a choice. Her eccentricities made it hard for me to resist a comic portrayal.

She was a woman—to take an example more or less at random—who found it impossible to imagine a situation that wouldn’t be enhanced by her presence.

When my sister, having a hard time in high school, said she thought she might benefit from talking to a therapist, my mother said, “I can be your therapist. Talk to me.”

“I think I’d like to talk to a professional,” Melinda said.

“I know more about psychology than most psychologists,” my mother said. In college she’d taken a psychology class.

One summer when I was in my twenties, I went to France, and when I was there I met someone—a subtle young woman named Sabine, who was getting a doctorate in philosophy. Sabine made plans to visit me in New York that fall. I mentioned this to my sister, and when my mother got wind of it, she offered to drive me to JFK to pick her up.

“It’ll be cheaper than a cab,” she pointed out. “Cheaper than the subway.”

“That’s an interesting idea,” I said. “ ‘Thank you for traveling five thousand miles to stay with me. Say hi to my mom.’ ”

“You won’t have to tell her I’m your mother. She won’t even know we’re related. I can just be the driver.”

I tried to picture this—my mother, perhaps wearing a chauffeur’s cap, pretending not to know me.

Great screen romances as reimagined by Tasha Morton. Casablanca: Bogart telling Bergman they’ll always have Paris, as they remember the magical evenings they spent there with his mom. Titanic, with Leonardo DiCaprio’s mother bobbing up and down in the water next to him.

The remarkable thing about her offer was that she was serious. She didn’t seem to see that it might not be a treat to have her there.

It wasn’t remarkable at all, really. It was Tasha.

But she was also a woman who, after the death of her husband—my father—had fallen into a state of despondency that she never really made her way out of. Who couldn’t bring herself to discard or give away his clothing or his cuff links or even his cigarettes, though his smoking had driven her to despair. Who, speaking at her old friend Ruby’s funeral a year after my father’s death, said three or four sentences about Ruby, and then, without realizing she was wandering off in the wrong direction, spent the rest of her time at the podium talking about him.

Write about her tragically or write about her comically: I didn’t want to write about her tragically, and when I was working on my first novel, I don’t think I could see any possibilities but those.

What I didn’t pause to think about was that she was much more than the sum of her eccentricities. No man is a hero to his valet, the saying goes, and few mothers are heroes to their sons.

What I didn’t pause to consider were things like these:

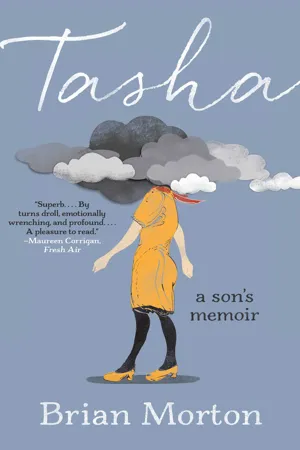

She left home when she was sixteen. Somehow she had the strength to do that, in 1941. Her first act after leaving home was an act of self-creation: she chose her name. Her given name was Esther, but in the Bronx of the 1940s, Esther was the name of every third girl on the street. She named herself Tasha, partly because she liked the sound and partly because it wasn’t the name of anyone she knew.

She was already working—she was the first-ever copy girl at the Daily Worker, a fact that she often cited proudly. Later she got a job at a labor union, the United Office and Professional Workers of America, where she met my father, who was an organizer there. When he dragged his feet about getting married, she took herself off to the newly founded state of Israel (“I told him to shit or get off the pot,” as she often put it) and lived on a kibbutz for six months. In the early 1950s, when she was in her late twenties, she began studying at NYU. She left school to have my sister and me, and resumed her education ten years later, receiving her BA and then her master’s in education, and started teaching in the public schools when she was almost forty. In the late 1960s and 197...