- 736 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

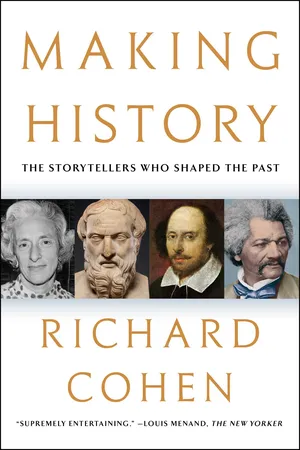

A “supremely entertaining” (The New Yorker) exploration of who gets to record the world’s history—from Julius Caesar to William Shakespeare to Ken Burns—and how their biases influence our understanding about the past.

There are many stories we can spin about previous ages, but which accounts get told? And by whom? Is there even such a thing as “objective” history? In this “witty, wise, and elegant” (The Spectator), book, Richard Cohen reveals how professional historians and other equally significant witnesses, such as the writers of the Bible, novelists, and political propagandists, influence what becomes the accepted record. Cohen argues, for example, that some historians are practitioners of “Bad History” and twist reality to glorify themselves or their country.

“Scholarly, lively, quotable, up-to-date, and fun” (Hilary Mantel, author of the bestselling Thomas Cromwell trilogy), Making History investigates the published works and private utterances of our greatest chroniclers to discover the agendas that informed their—and our—views of the world. From the origins of history writing, when such an activity itself seemed revolutionary, through to television and the digital age, Cohen brings captivating figures to vivid light, from Thucydides and Tacitus to Voltaire and Gibbon, Winston Churchill and Henry Louis Gates. Rich in complex truths and surprising anecdotes, the result is a revealing exploration of both the aims and art of history-making, one that will lead us to rethink how we learn about our past and about ourselves.

There are many stories we can spin about previous ages, but which accounts get told? And by whom? Is there even such a thing as “objective” history? In this “witty, wise, and elegant” (The Spectator), book, Richard Cohen reveals how professional historians and other equally significant witnesses, such as the writers of the Bible, novelists, and political propagandists, influence what becomes the accepted record. Cohen argues, for example, that some historians are practitioners of “Bad History” and twist reality to glorify themselves or their country.

“Scholarly, lively, quotable, up-to-date, and fun” (Hilary Mantel, author of the bestselling Thomas Cromwell trilogy), Making History investigates the published works and private utterances of our greatest chroniclers to discover the agendas that informed their—and our—views of the world. From the origins of history writing, when such an activity itself seemed revolutionary, through to television and the digital age, Cohen brings captivating figures to vivid light, from Thucydides and Tacitus to Voltaire and Gibbon, Winston Churchill and Henry Louis Gates. Rich in complex truths and surprising anecdotes, the result is a revealing exploration of both the aims and art of history-making, one that will lead us to rethink how we learn about our past and about ourselves.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Making History by Richard Cohen in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Historical Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1 THE DAWNING OF HISTORY Herodotus or Thucydides?

The conversion of legend-writing into the science of history was not native to the Greek mind, it was a fifth-century invention, and Herodotus was the man who invented it.—R. G. COLLINGWOODExiled Thucydides knew All that a speech can say About Democracy, And what dictators do, The elderly rubbish they talk To an apathetic grave; Analysed all in his book.—W. H. AUDEN, “SEPTEMBER 1, 1939”

NO ONE KNOWS FOR SURE the dates of Herodotus’s own story. He was probably born c. 485 B.C. and lived into the 420s, since he refers to events early in the Peloponnesian War of 431–404. He was part of an intellectual world that included early medical investigations and creative speculation of all kinds. Among his contemporaries or near-contemporaries were Aeschylus (525–456 B.C.), Aristophanes (c. 448–c. 380 B.C.), Euripides (c. 484–c. 408 B.C.), Pindar (522–c. 443 B.C.), Plato (c. 429–347 B.C.), and Sophocles (496–406 B.C.), who composed a poem in his honor.

Most records before Herodotus are dry chronicles, even those that evince a rudimentary attempt at narrative. There is no evidence of “history” as a concept, although the Hebrew words toledot (genealogies) and divre hayyamin (the matter of those days) suggest at least some interest in tracking the past. Homer, best treated as a plural noun, a group effort that produced The Iliad and The Odyssey, provided a way station on the road to writing history. As Adam Nicolson puts it in Why Homer Matters: “Epic, which was invented after memory and before history, occupies a third space in the human desire to connect the present to the past: it is the attempt to extend the qualities of memory over the reach of time embraced by history.” He dates the oral creation of both poems to c. 1800 B.C., their being written down to around 700 B.C.

The Greeks knew something of their past from these oral traditions, often versified, but anything that occurred more than three generations distant would be only loosely remembered if not forgotten altogether. Oral customs tend to avoid stories that an audience doesn’t want to hear. In 492, when Phrynikhos, one of Aeschylus’s rivals, presented his play The Fall of Miletus on that city’s destruction by the Persians, “the audience burst into tears, fined him 1,000 drachmas for reminding them of their own evils, and ordered that no one should ever perform this play again.” Herodotus would have known that poets from a previous age were primarily there to please those who had come to hear them and so often made things up, even if they protested that they never did such things.

Of those previous poets, Hesiod (active c. 700 B.C.) had introduced the idea of a succession of declining ages. Hecataeus of Miletus (550–476 B.C.), whose Journey Round the World was built on his travels around the Mediterranean, is otherwise the most significant predecessor. Among other notable writers, Hellanicus of Lesbos (c. 490–405 B.C.) wrote long parallel chronologies, listing not just a single line of rulers, and Philistus, Theopompus, and Xenophon, all of whom flourished in the fourth century B.C., wrote accounts of real value.

This line of historians encompassed a revolution. Between 2000 and 1200 B.C., the unnamed people whom we retrospectively call Indo-Hittites burst over Europe and South Asia, and one of these invading tribes raised a group of small settlements around the Mediterranean and the Black Sea. When this hyper-dynamic culture came into contact with another of a similar nature, a new consciousness began to grow. These years saw substantial advances in abstract reasoning, and people began to connect with the past in a new way. (It is worth bearing in mind that the Inca, that most ordered of preliterate cultures, had four versions of history, ranging from secret to popular, all propagated under the empire’s strict control.)

An 1814 imagining of Homer and his audience. In the sixth century B.C., a popular poem had spoken of “the sweetest of all singers,” identifying him as “a blind man and he makes his home in rocky Chios.” This “evidence” was enough for Thucydides to declare, a century on, that Homer was the author alluded to.

Some historians argue that the victory at Marathon in 490 B.C. during the first Persian invasion of Greece marked East and West as different cultural entities and so was a turning point. The Greek golden age possibly coincided with a surge of abundance, akin to that which preceded the Industrial Revolution in Britain, with higher rates of food production, capital investment, and a leap in population. But the resultant cultural explosion was matched only once in history, by the Renaissance in Europe, and although “history” was not at any one point in time a necessary development, certain discoveries are requisite if a civilization is to evolve, and a sense of the past is one of them.

Although writing had begun in Sumeria (southern Iraq) by the third millennium B.C., it was Herodotus who authored the oldest surviving book-length work of prose on any subject. He wrote the first account in the Western tradition that is recognizably a work of history as we might now define it, covering the recent human past and not concentrating on myth and legend (although not by any means passing over them, either; he would likely have agreed with Plato’s declaration in the Republic that myth is “the noble lie” or pious fiction that binds society together). He is also the first to provide a sustained record of past occurrences along with self-conscious discussions about how to obtain knowledge of days gone by and the first to ponder why particular events happened in the first place. Above all, he asks questions. He is the world’s first travel writer, investigative reporter, and foreign correspondent. He covers ethnography (which existed as a literary genre prior to history, so its incorporation into The Histories is not surprising), military and local history, biography, poetry, philology, genealogy, mythography, anthropology, geology, botany, zoology, and architecture, while at the same time he is, to use Ryszard Kapuściński’s description in his Travels with Herodotus, “a typical wanderer… a pilgrim… the first to discover the world’s multicultural nature. The first to argue that each culture requires acceptance and understanding, and that to understand it, one must first come to know it.”

The immediate impression on reading even a few of his pages is that he finds everything of interest. Sometimes he offers a judgment, at others just reports; his approach characterized by opsis (“seeing”), from which we get a word more associated with crime novels—autopsy, “seeing for oneself.” Much of his knowledge comes from the voyages that Greeks, Egyptians, and Phoenicians had been making both around the Mediterranean and outside it, but it is likely he traveled extensively, not only throughout the Greek states but to Egypt, Phoenicia (roughly, modern Lebanon and Syria), Babylon (Iraq), Arabia, Thrace (Bulgaria and the European section of Turkey), and up through modern Romania, Ukraine, southern Russia, and Georgia.

Most of these journeys were formidable undertakings. To get to what is modern Odessa, for instance, he would have had to voyage along the western and northern shores of the Aegean; then through the Dardanelles, the Sea of Marmara, and the Bosporus; and last, along the western shore of the Black Sea, past the mouth of the Danube to that of the Dnieper: with fair winds and no mishaps, a voyage likely to have taken three months—and that was just one of many trips. The two most powerful Greek cities of the time were Athens—its citizen population just 100,000—and Sparta, to the south. (The latter’s citizens were called Spartiatai, but an alternative form was Lakon, from which comes “laconic”: Spartans were known for their terse speech, hence when in c. 338 B.C. Philip of Macedon told them, “If I invade your territory, I will destroy you,” they sent back a one-word reply: “If.”)

Herodotus’s home city of Anatolian Halicarnassus was on the edge of what was then the vast cultural space of the ancient Near East, a Greek colony that in about 545 B.C. had been absorbed into the Persian Empire along with Lydia (covering much of what is now western Turkey). Caught between two worlds, the city had a non-Greek native population—known as Carians—and drifted away from its close relations with its Dorian neighbors to help pioneer Greek trade with Egypt, which was becoming an internationally-minded port.

Because of an uncle’s fondness for political intrigue, Herodotus found his family put under a cloud and himself, at the age of around thirty, sent away from Halicarnassus (today’s Bodrum, a small city on the southwest coast of Turkey). For much of the next five years he traveled, landing in Athens in c. 447 B.C., already armed with a rich store of notes about the eastern Mediterranean. He originally began his history of the area with the Persian attack on the city in 490 B.C., then expanded it to cover Persia’s invasion of the whole peninsula ten years later—the defining event of his boyhood. One story, likely a myth, has Herodotus as a child standing on the quay at Halicarnassus as the defeated ships returned from the Battle of Salamis and asking, “Mother, what did they fight each other for?”

In 499 B.C. the Carians had joined with the Greek coastal towns in revolting against Persia; by the time Herodotus left on his travels, his family, one of the noblest (and most politically involved) of the city, would likely have had connections in other parts of the Persian kingdom that would have made his researches easier. Xenía, the Greek word for the concept of courtesy shown to those far from home, is generally translated as “guest-friendship” because the ways in which hospitality was exercised created a reciprocal relationship between guest and host. In addition, Herodotus, although he spoke only Greek comfortably, would have enjoyed the institution of the proxenos, “the guest’s friend,” a type of consul who voluntarily or for a fee cared for visitors from his native city. Finally, no one could be sure of new arrivals whether they were merely human or gods in human form: best to be hospitable.

Possibly Herodotus began as a sea captain and merchant. His knowledge of geography is well ahead of that of his known predecessors, and he takes for granted climate, topography, and access to resources. Before him, there is scant evidence that anyone was interested in preserving knowledge of the causes of recent events; Greek states had no state archives or even lists of magistrates to help construct a chronology. Athens, remarkable for its concern for commemoration, lacked a central archive until the end of the fifth century.

Herodotus planned both to instill a sense of the past and to leave a record, but he also gave his curiosity full rein. His book contains, to borrow one recent biographer’s list, “illicit eroticism, sex, love, violence, crime, strange customs of foreign peoples, imagined scenes in royal bedrooms, flashbacks, dream sequences, political theory, philosophical debate, encounters with oracles, geographical speculation, natural history, short stories and Greek myths.” Herodotus notes, with typical fascination, that Egyptians eat in the street and relieve themselves indoors; their men urinate sitting down, their women standing up (2.35, 2–3), whereas in the Greek world the reverse applied. Ethiopians, he observes blithely, speak a language unlike any other, squeaking like bats (4.183) or twittering like birds (2.57). He loves to report strange deeds of all kinds, to “seek out side issues” (4.30). Aristophanes satirized his opening line of inquiry as “look at the women” or, as we might joshingly put it, Cherchez la femme, for he is evidently fascinated by sexual conventions. Thus, of Libyan customs: “When a Nasamonian man marries for the first time, it is customary for his bride to have intercourse with all the guests at the feast in succession, and for each of these guests to then present a gift he has brought.” Among another Libyan tribe, the Gindanes, the women “wear many leather ankle bracelets. It is said that they put on one of these for every man with whom they have had intercourse, and the woman who wears the most is considered to be the best, since she has won affection from the most men” (4.172, 4.176). His handling of the telling detail can take one’s breath away: when in 479 B.C. the Athenians held a prolonged siege of Sestos, on the Hellespont, “within the city wall, the people by now were reduced to utter misery, even to the point of boiling the leather straps of their beds and eating them” (9.118). One wonders how Herodotus knew this.

At one point in his account of Xerxes’s campaigns, the ruthless, all-mighty ruler of the vast Persian empire, the largest realm the world had ever seen, is surveying the great host of men he has called up to overwhelm the Greeks:

As Xerxes looked over the whole Hellespont, whose water was completely hidden by all his ships, and at all the shores and the plains of Abydos, now so full of people, he congratulated himself for being so blessed. But then he suddenly burst into tears.…

When one of his officers asks what has caused such sorrow, Xerxes replies: “I was overcome by pity as I considered the brevity of human life, since not one of all these people here will be alive one hundred years from now” (7.46). The Persian monarch is not always so compassionate. Herodotus, who tends to invest Persians with the characteristics that the Greeks most despised, notes that just a few weeks later, Xerxes was forced to beat a hasty retreat back home. A storm threatened his ship:

The King fell into a panic and shouted to the helmsman, asking if there was any way they could be saved. The helmsman replied, “My Lord, there is none, unless we rid ourselves of these many men on board.” Upon hearing this, Xerxes said, “Men of Persia, it is now the time for you to prove your care for your king. For in you, it seems, lies my safety.” After he had said this, his men prostrated themselves, leapt out into the sea, and the now lightened ship sailed safely to Asia. As soon as Xerxes stepped safely onto shore, he gave the helmsman a gift of a golden crown in return for saving his life, but then, because he had been responsible for the death of so many Persians, he had his head cut off. (8.118)

Herodotus several times writes that he does not believe this or other stories he tells but feels he must repeat them because they are too good to leave out. Talking of livestock in Scythia, he suddenly says, “a remarkable fact occurs to me (I need not apologize for the digression—it has been my plan throughout this work).” After the powerful anecdote of the boatswain, he adds that readers should not regard it as a historical fact (8.118–19); the tale is included because it embodies how a tyrant exercises “justice,” and its ideological significance outweighs, for him, its likely historical falseho...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Epigraph

- List of Illustrations and Photographic Credits

- Preface

- Overture: The Monk Outside the Monastery

- Chapter 1: The Dawning of History: Herodotus or Thucydides?

- Chapter 2: The Glory that was Rome: From Polybius to Suetonius

- Chapter 3: History and Myth: Creating the Bible

- Chapter 4: Closing Down the Past: The Muslim View of History

- Chapter 5: The Medieval Chroniclers: Creating a Nation’s Story

- Chapter 6: The Accidental Historian: Niccolò Machiavelli

- Chapter 7: William Shakespeare: The Drama of History

- Chapter 8: Zozo and the Marionette Infidel: M. Voltaire and Mr. Gibbon

- Chapter 9: Announcing a Discipline: From Macaulay to von Ranke

- Chapter 10: Once Upon a Time: Novelists as Past Masters

- Chapter 11: America Against Itself: Versions of the Civil War

- Chapter 12: Of Shoes and Ships and Sealing Wax: The Annales School

- Chapter 13: The Red Historians: From Karl Marx to Eric Hobsbawm

- Chapter 14: History from the Inside: From Julius Caesar to Ulysses S. Grant

- Chapter 15: The Spinning of History: Churchill and His Factory

- Chapter 16: Mighty Opposites: Wars Inside the Academy

- Chapter 17: The Wounded Historian: John Keegan and the Military Mind

- Chapter 18: Herstory: From Bān Zhāo to Mary Beard

- Chapter 19: Who Tells Our Story?: From George W. Williams to Ibram X. Kendi

- Chapter 20: Bad History: Truth-Telling vs. “Patriotism”

- Chapter 21: The First Draft: Journalists and the Recent Past

- Chapter 22: On Television: From A.J.P. Taylor to Henry Louis Gates, Jr.

- Photographs

- Afterword

- Acknowledgments

- About the Author

- Notes

- Index

- Image Descriptions

- Copyright