- 304 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

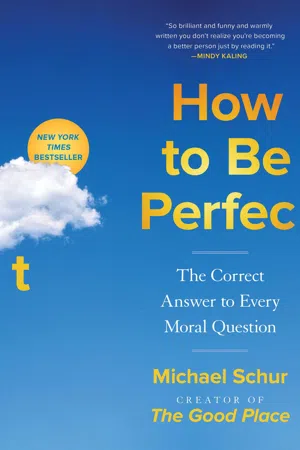

From the creator of The Good Place and the cocreator of Parks and Recreation, a hilarious, thought-provoking guide to living an ethical life, drawing on 2,400 years of deep thinking from around the world.

Most people think of themselves as “good,” but it’s not always easy to determine what’s “good” or “bad”—especially in a world filled with complicated choices and pitfalls and booby traps and bad advice. Fortunately, many smart philosophers have been pondering this conundrum for millennia and they have guidance for us. With bright wit and deep insight, How to Be Perfect explains concepts like deontology, utilitarianism, existentialism, ubuntu, and more so we can sound cool at parties and become better people.

Schur starts off with easy ethical questions like “Should I punch my friend in the face for no reason?” (No.) and works his way up to the most complex moral issues we all face. Such as: Can I still enjoy great art if it was created by terrible people? How much money should I give to charity? Why bother being good at all when there are no consequences for being bad? And much more. By the time the book is done, we’ll know exactly how to act in every conceivable situation, so as to produce a verifiably maximal amount of moral good. We will be perfect, and all our friends will be jealous. OK, not quite. Instead, we’ll gain fresh, funny, inspiring wisdom on the toughest issues we face every day.

Most people think of themselves as “good,” but it’s not always easy to determine what’s “good” or “bad”—especially in a world filled with complicated choices and pitfalls and booby traps and bad advice. Fortunately, many smart philosophers have been pondering this conundrum for millennia and they have guidance for us. With bright wit and deep insight, How to Be Perfect explains concepts like deontology, utilitarianism, existentialism, ubuntu, and more so we can sound cool at parties and become better people.

Schur starts off with easy ethical questions like “Should I punch my friend in the face for no reason?” (No.) and works his way up to the most complex moral issues we all face. Such as: Can I still enjoy great art if it was created by terrible people? How much money should I give to charity? Why bother being good at all when there are no consequences for being bad? And much more. By the time the book is done, we’ll know exactly how to act in every conceivable situation, so as to produce a verifiably maximal amount of moral good. We will be perfect, and all our friends will be jealous. OK, not quite. Instead, we’ll gain fresh, funny, inspiring wisdom on the toughest issues we face every day.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

PART ONE

In Which We Learn Various Theories About How to Be Good People from the Three Main Schools of Western Moral Philosophy That Have Emerged over the Last 2,400 Years, Plus a Bunch of Other Cool Stuff, All in Like Eighty Pages

CHAPTER ONE Should I Punch My Friend in the Face for No Reason?

No. You shouldn’t. Was that your answer? Sweet. You’re doing great so far.

If I surveyed a thousand people and asked them if they think it’s okay to punch their friends in the face for no reason, I’d bet all thousand would say no.1 This person is our friend. This person did nothing wrong. We should not, therefore, punch our friend in the face. But the weird thing about asking why we shouldn’t do this, despite how obvious it seems, is that we may stumble trying to formulate an answer.

“Because, you know, it’s… bad.”

Even sputtering out that simplistic explanation is weirdly encouraging—it means we’re aware that there’s an ethical component to this action, and we’ve determined it’s, you know… “bad.” But to become better people, we need a sturdier answer for why we shouldn’t do it than “because it’s bad.” Understanding an actual ethical theory that explains why it’s bad can then help us make decisions about what to do in a situation that’s less morally obvious than “Should I punch my friend in the face for no reason?” Which is just about every other situation.

An obvious place to start might be to say, well, a good person doesn’t generally do things like that, and a bad person does, and we want to be good people. The next step would be to better define what a “good person” really is, and that’s trickier than it might seem. The initial idea behind The Good Place was that a “bad” woman, who had lived a selfish and somewhat callous life, is admitted to an afterlife paradise due to a clerical error and finds herself ticketed for an idyllic eternity alongside the very best people who ever lived—people who’d spent their time removing landmines and eradicating poverty, whereas she’d spent her life littering, lying to everyone, and remorselessly selling fake medicine to frightened seniors. Scared she’s going to be discovered, she decides to try to become a “good” person in order to earn her spot. I thought that was a fun idea, but I also quickly realized I had no idea what it really meant to be “good” or “bad.” I could describe actions as “good” or “bad”—

- sharing good

- murder bad

- helping friends good

- punching friends in the face for no reason bad

—but what was underlying those behaviors? What’s an all-encompassing, unifying theory that explains “good” or “bad” people? I got lost trying to find it—which is what led me to moral philosophy, which then led me to producing the show, which eventually led me to writing a book where I spend twenty-two pages trying to explain why it’s not cool to randomly coldcock your buddy.

Philosophers describe “good and bad” in a bunch of different ways, and we’ll touch on many of them in this book. Some of them do in fact approach the concepts of good and bad through actions—they say that good actions obey certain principles that we can discover and then follow. Others say a good action is whatever creates the most pleasure and the least pain. One philosopher even suggests that goodness comes from being as selfish as we possibly can and caring only about ourselves. (Really. She says that.) But the first theory we’re going to talk about—the oldest of the Big Three, called “virtue ethics”—tries to answer the question that initially stumped me: What makes a person good or bad? Virtue ethicists define good people as those who have certain qualities, or “virtues,” that they’ve cultivated and honed over time, so that they not only have these qualities but have them in the exact right amount. Seems gettable, right?

Although… immediately we’re hit with a hundred other questions: Which qualities? How do we get them? How do we know when we’ve gotten them? This happens a lot in philosophy—the second you ask a question, you have to back up and ask fifty other questions just so you know that you’re asking the right question and that you understand why you’re even asking it, and then you have to ask questions within those questions, and you keep backing up and widening out and getting more and more foundational in your investigation until finally a German fascist is trying to figure out why there are even “things.”

We also might wonder if there’s a single way to define a “good” person; after all, as the author Philip Pullman once wrote, “People are too complicated to have simple labels.” We are all highly individualized products of both nature and nurture—complex swirls of inherent personality traits, things learned from teachers and parents and friends, life lessons we picked up from Shakespeare2 and/or the Fast & Furious movies.3 Is it possible to describe a set of qualities we all have to have, in the exact right amount, that will make every one of us “good”? To answer that, we need to unlearn all the stuff we’ve learned—we need to reset, take ourselves apart, and then build ourselves back up with a sturdier understanding of what the hell we’re doing and why the hell we’re doing it. And to help us do that, we turn to Aristotle.

“A Flowing River of Gold”

Aristotle lived from 384 to 322 BCE, and wrote the most important stuff about the most important stuff. If you want to feel bad about yourself and your measly accomplishments, poke around his Wikipedia page. It’s estimated that less than a third of what he actually wrote has survived, but it covers the following subjects: ethics, politics, biology, physics, math, zoology, meteorology, the soul, memory, sleep and dreams, oratory, logic, metaphysics, politics, music, theater, psychology, cooking, economics, badminton, linguistics, politics, and aesthetics. That list is so long I snuck “politics” in there three times without you even noticing, and you didn’t so much as blink when I claimed he wrote about “badminton,” which definitely didn’t exist in the fourth century BCE. (I also don’t think he ever wrote about cooking, but if you told me Aristotle had once tossed off a four-thousand-word papyrus scroll about how to make the perfect chicken Parm, I wouldn’t blink an eye.) His influence over the history of Western thought cannot be overstated. Cicero even described his prose as “a flowing river of gold,” which is a very cool way for a famous statesman and orator to describe your writing. (Although, also: Take it down a notch, Cicero. Coming off a little thirsty.)

For the purposes of this book, though, we’re only concerned with Aristotle’s take on ethics. His most important work on the subject is called the Nicomachean Ethics, named either in honor of his father, Nicomachus, or his son, Nicomachus, or I suppose possibly a different guy named Nicomachus that he liked better than either his dad or his kid. Explaining what makes a person good, instead of focusing on what kinds of things such a person does, requires several steps. Aristotle needs to define (1) which qualities a good person ought to have, (2) in which amounts, (3) whether everyone has the capacity for those qualities, (4) how we acquire them, and (5) what it will look (or feel) like when we actually have them. This is a long to-do list, and walking through his argument takes a little patience and time. Some of the thinkers we’ll meet later have theories that can be decently presented in a few sentences; Aristotle’s ethics is more of a local train, making many stops. But it’s an enjoyable ride!

When Do We Arrive at “Good Person” Station?

It might seem odd to begin with the final question noted in the last paragraph, but that’s actually how Aristotle does it. He first defines our ultimate goal—the very purpose of being alive, the thing we’re shooting for—the same way a young swimmer might identify “Olympic gold medal” as a target that would mean “maximum success.” Aristotle says that thing is: happiness. That’s the telos,4 or goal, of being human. His argument for this is pretty solid, I think. There are things we do for some other reason—like, we work in order to earn money, or we exercise in order to get stronger. There are also good things we want, like health, honor, or friendships, because they make us happy. But happiness is the top dog on the list of “things we desire”—it has no aim other than itself. It’s the thing we want to be, just… to be it.

Technically, in the original Greek, Aristotle actually uses the nebulous word “eudaimonia,” which sometimes gets translated as “happiness” and sometimes as “flourishing.”5 I prefer “flourishing,” because that feels like a bigger deal than “happiness.” We’re talking about the ultimate objective for humans here, and a flourishing person sounds like she’s more fulfilled, complete, and impressive than a “happy” person. There are many times when I’m happy, but I don’t feel like I’m flourishing, really. Like, it’s hard for me to imagine a greater happiness than watching a basketball game and eating a sleeve of Nutter Butters, but am I flourishing when I do that? Is that my maximum possible level of fulfillment? Is that the be-all and end-all of my personal potential? (My brain keeps trying to answer “Yes!” to these rhetorical questions, and if that’s true it’s kind of sad for me, so I’m just going to power through, here.) Aristotle actually anticipated this tension, and resolved it by explaining that happiness is different from pleasure (the kind associated with hedonism), because people have brains and the ability to reason. That means the kind of capital-H Happiness he’s talking about has to involve rational thought and virtues of character, and not just, to give one example off the top of my head, the NBA Finals and a Costco bucket of peanut butter cookies.

If “flourishing” is still a bit slippery as a concept, think of it this way: You know how some people who are really into jogging talk about a “runner’s high”? It is (they claim) a state of euphoria they achieve late in a long race, where they suddenly don’t even feel like they’re tired or laboring because they’ve “leveled up” and are now superhuman running gods, floating above the course, buoyed by the power of Pure Running Joy. Two things to say about this: First, those people are dirty liars, because there is no way to achieve higher-level enjoyment from running, because there’s no way to achieve any enjoyment from running, because there is nothing enjoyable about running. Running is awful, and no one should ever do it unless they’re being chased by a bear. And second, Aristotle’s flourishing, to me, is a sort of “runner’s high” for the totality of our existence—it’s a sense of completeness that flows through us when we are nailing every aspect of being human.

So in Aristotle’s view, the very purpose of living is to flourish—just like the purpose of a flute is to produce beautiful music, and the purpose of a knife is to cut things perfectly. And it sounds awesome, right? #LivingOurBestLives? Just totally acing it? Aristotle’s a good salesman, and he gets us all excited with his pitch: we can all, in theory, achieve this super-person status. But then he drops the hammer: If we want to flourish, we need to attain virtues. Lots of them. In precise amounts and proportions.

What Are Virtues?

We can think of virtues as the aspects of a person’s makeup that we admire or associate with goodness; basically, the qualities in people that make us want to be their friends—like bravery, temperance, generosity, honesty, magnanimity, and so on.6 Aristotle defines virtues as the things that “cause [their] possessors to be in a good state and to perform their functions well.” So, the virtues of a knife are those qualities that make it good at being a knife, and the virtues of a horse are the horse’s inherent qualities that make it good at galloping and other horsey stuff. The human virtues he listed, then, are the things that make us good at being human. This seems kind of redundant, at first glance. If on day one of tennis lessons our instructor told us that “the virtues of a good tennis player are the things that make us good at tennis,” we’d likely nod, pretend to get a phone call, and then cancel the rest of our session. But the analogies make perfect sense:

THE THING | ITS VIRTUES | ITS PURPOSE |

|---|---|---|

Knife | Sharpness, blade strength, balance, etc. | Cutting things well |

Tennis player | Agility, reflexes, court vision, etc. | Playing great all-around tennis |

Human | Generosity, honesty, courage, etc. | Flourishing/happiness |

We now know what we need (virtues) and we know what they’ll do for us (help us flourish). So… how do we get them? Do we already have them, somehow? Were we born with them? Sadly, there’s no easy fix here. Acquiring virtues is a lifelong process, and it’s really hard. (I know, it’s a bummer. When Eleanor Shellstrop—Kristen Bell’s character from The Good Place—asks her philosophy mentor Chidi Anagonye how she can become a good person, she wonders if there’s a pill she can take, or something she can vape. No such luck.)

How Do We Get These Virtues?

Unfortunately, in Aristotle’s view, no one’s just born inherently and completely virtuous—there’s no such thing as a baby who already possesses sophisticated and refined versions of all of these great qualities.7 But we’re all born with the potential to get them. All people have what he calls “natural states” of virtue: “Each of us seems to possess his type of character to some extent by nature; for in fact we are just, brave, prone to temperance, or have another feature, immediately from birth.” I think of these as “virtue starter kits”—basic tools and crude maps that kick off our lifelong quest for refined virtues. Aristotle says these starter kits are the coarse character traits possessed by children and animals—which, if you’ve ever taken a bunch of ten-year-old boys to Dave & Buster’s, you know are often indistinguishable.

We can all probably identify some starter kit we had as kids. From a very early age I was an extreme rule follower—or maybe let’s say I was “inclined toward the virtue of dutifulness,” so I don’t sound like such a suck-up. It takes a tremendous amount of convincing for me to break any rule, no matter how minimal the potential punishment, because my personal virtue starter kit for dutifulness came extremely well equipped—lots of tools in there. One of them is this little voice in my head—present as far back as I can remember—that starts chirping at me if anyone violates a rule, and it doesn’t stop until the rule is followed.8 When I was a freshman in college, our dorm had a rule that all loud music had to be off by one a.m. If I was at a party at on...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Epigraph

- Introduction

- Part One

- Part Two

- Part Three

- Acknowledgments

- About the Author

- Notes

- Index

- Copyright

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access How to Be Perfect by Michael Schur in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Philosophy & Ethics & Moral Philosophy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.