![]()

1

The Petrine Revolution at Home

On a chilly January day in 1689, the seventeen-year-old Peter Alekseevich Romanov, co-ruler of Russia since 1682, wed Eudokia Lopukhina, three years his senior. Arranged by Peter’s mother, Natalia Naryshkina, the marriage served at least two strategic objectives—first, to demonstrate that Peter had become a man and, second, to ensure the production of a male heir before Peter’s older half-brother and co-ruler, Ivan, succeeded in siring one himself. Likewise strategic was the choice of Lopukhina. Deriving from a lesser gentry clan, she enabled the Naryshkins to minimize the rivalries among prominent families that usually attended the selection of a royal bride. There exists no evidence that the groom participated in his bride’s selection; he also appears to have developed no real attachment to her. Over the following years, he acquired a mistress in the German quarter of Moscow and became involved in numerous sexual liaisons while travelling abroad. The bridegroom—the future Peter the Great—nevertheless did his duty. Thirteen months after the wedding, Eudokia delivered a baby boy, Alexis, who became heir to the throne; twenty months later she delivered a second child, who died the following May.1

Although the stakes were very rarely so high or the groom so powerful, the first marriage of Peter the Great was nevertheless typical of his times in almost every other way, including the decisive role of elders, their pragmatism in selecting the spouse, and the youth of both bride and groom.

Marriage in Muscovy

Marriage was virtually universal in Muscovite Russia, where popular belief held that everyone should wed, except perhaps people who suffered from a physical or mental disability so serious that it made laboring impossible. Marriage might serve a range of purposes. Behind the façade of Muscovite autocracy, for example, boiar clans deployed marriage in their maneuverings for power and patronage, with marriage into or kinship ties with the grand princely family the coveted prize.2 Some provincial gentry likewise deployed the marriage of daughters to gain access to higher social circles in Moscow. Although the majority of marriages united people from identical or comparable social and economic backgrounds, practical goals governed their marital arrangements, too.3

For the tax-paying population of the towns and countryside, marriage was first and foremost an economic necessity: it forged the working unit—husband and wife—upon which virtually every adult depended. But marriage was often advantageous in other ways as well. It generated alliances between kinship networks and encouraged their cooperation, thereby, for example, fostering the enterprises of merchants and townspeople and providing access to capital—the dowry. At a time when no banks existed and borrowing, although quite common, brought weighty personal obligations and sometimes crushing rates of interest, this was no minor matter.4 In the countryside, marriage linked gentry neighbor to gentry neighbor, consolidating not only parcels of land but also more broadly a sense of local community.5 Far from least, marriage furthered social stability. It harnessed the elemental power of human sexuality to the practical purpose of procreation and the transmission of property, and subjected potentially unruly women to the disciplinary control of a man.6

Among the purposes of marriage was, emphatically, not emotional or sexual pleasure, at least according to official morality. It is true that spouses were supposed to “love” one another. But this was an elevated kind of love, analogous to “to the spiritual love of the union between Christ and his church and between God and his children.” This feeling of love differed utterly from romantic love, a dangerous emotion best kept under strict control.7 Such strictures did not prevent at least some married couples from developing deep attachments to one another that might well be construed as “love.”8 And no doubt some people experienced passionate attraction and acted on that feeling. Criminal cases that reveal illicit relationships offer an occasional glimpse of individuals swept away by their passions. The love charms and spells against which the church regularly inveighed also suggest popular interest in earthly pleasures.9 But those pleasures were not supposed to be the point of marriage.

The varied purposes marriage could serve meant that spousal choice remained far too important to be left to the whims or attractions of the couple most directly involved. This was especially true if the couple were young, the norm in most first marriages. At the onset of the eighteenth century, Russian girls became legally marriageable at age twelve; the age was raised to thirteen at the century’s end. True, most marriages occurred later than that—at the start of the century, men rarely married before the age of twenty; their brides were slightly younger. But then, toward the century’s end, men’s age of marriage dropped to seventeen or eighteen and women’s, to fifteen and a half.10

It is possible that Peter the Great’s household-based taxation and recruitment policies contributed to that decline. They encouraged both the consolidation of households and youthful unions in which newlyweds lived in the household of parents—usually the grooms’ but sometimes the brides’—for years following the marriage if not for good. In turn, living with parents or elders freed young couples of the need to obtain resources sufficient to establish their own household before marrying, as their Western European counterparts often had to do. Early marriages were also fruitful marriages, greatly valued by a society where agriculture provided the basis of almost everyone’s livelihood, and at a time of high infant mortality and short lifespans.

Elders played a vital role at every stage of the marital arrangements of both men and women. Senior members of a suitor’s household identified potential partners with the aid of relatives, friends, or a matchmaker. Either by themselves or with the assistance of a go-between, elders looked over candidates’ households to establish their suitability and economic well-being and evaluated potential brides and their immediate kin. Then they made their choice. A go-between facilitated the all-important negotiations concerning the dowry and other financial and practical arrangements accompanying the match. Once the parties reached an agreement, they formalized it as a contract, with the two sides exchanging visits and gifts. As much a public as a personal matter, the engagement was almost as significant as the wedding itself: breaching the contract brought serious penalties.11

The wedding soon followed. It was an elaborate occasion—how elaborate depended on the wealth of the couples’ households—and it included days of feasting and celebrating. It also might be the first time that the bride laid eyes on her husband, especially if the couple belonged to social elites. Gathering together kin and community as witnesses and future support, the celebrations included the showing of the bloody bridal shirt, proof of the bride’s virginity. A Russian Orthodox priest consecrated the marriage, the key moment of the ceremony. Otherwise, however, the church played no direct role in the marriage celebration.12

Russian Orthodoxy and Marriage

Nevertheless, the Russian Orthodox faith influenced marriage profoundly, and on multiple levels. For one thing, canon law disqualified potential spouses. Bride and groom could not be related too closely by blood or by marriage or be linked in “fictive kinship,” that is, have participated in the same christening. Officiating priests carefully investigated beforehand to ensure that couples conformed to these rules. If they failed to do so, the priest would refuse to consecrate the marriage and without that, a wedding lacked legal standing. For another, the religious calendar determined the timing of almost all weddings. Orthodoxy prohibited weddings during the four main fasts of the year and also on weekly fast days (every Wednesday and Friday). The vast majority of Muscovites honored these prohibitions. Judging at least by the timing of births, they also observed the prohibition on sexual activity that religion imposed during the Lenten period.13 Whether couples also abstained on weekly fast days, as their faith dictated, remains unknown.

In addition, the church sought to limit the number of a person’s marriages to one, although in this it proved less successful. While acknowledging sexual appetites, Orthodox officials nevertheless disapproved of them, regarding chastity as preferable even for married couples. Only an elect few could manage chastity, however. Marriage was necessary for everyone else, a concession to the flesh and to the need for procreation. That necessity encompassed Russian Orthodox priests, whom the church required to marry. But because marriage established what was conceived to be an unbreakable bond not only on earth but also in the hereafter, officials regarded the first as the sole legitimate marriage. Thus, the church permitted priests to marry only once.

With the additional marriages of everyone else, the Church struggled. Frowning upon divorce and regarding remarriage, even of widows and widowers, as a “regrettable necessity,” church officials worked hard to discourage second marriages; regarded third marriages with enormous suspicion; and forbade fourth marriages altogether. The marriage ritual differed for widows or widowers and they had to perform acts of penance and pay higher marriage fees. Nevertheless, given high mortality rates, appeals for permission for second, even third, marriages were commonplace. Recognizing church preferences, others who had lost a spouse sometimes sought to conceal their earlier unions in order to gain permission to marry again.14 They did so not only—or not even—because they required a sexual partner but because the roles of husband and wife were complementary and each depended so thoroughly on the other’s labor. As a result, households headed by widows, with or without children, were almost invariably very poor. Unless they held property, widows also found it difficult to find a new husband. Widowers, by contrast, remarried frequently.15

Husbands and Wives

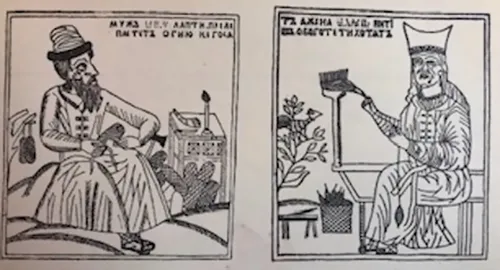

At every level of society, marriage entailed the cooperation of a man and a woman; among the tax-paying population, a viable household required the labor of both. In return for the wife’s dowry, custom obliged her husband to shelter her and provide her with food, drink, and clothing. In so doing, the husband gained the right to his wife’s reproductive capacity and labor, the latter almost always both varied and highly demanding. Households were economic units in towns as well as the countryside. Merchants and craftsmen, for instance, worked from home and their houses—often one- or two-room wooden cabins—were arranged to accommodate their trade.

FIGURE 1.1 The husband manufactures sandals while the wife spins thread. Lubok. From Russkii lubok XVII-XIX vv (Moscow-Leningrad: IZOGIZ, 1962). © 19th century, public domain.

Except, perhaps, for social elites, even in towns (including Moscow) almost every household was also a homestead (dvor, in Russian), a kind of small farm that usually included a kitchen garden, some fruit trees, and various domestic animals—fowl, cows, goats, pigs. If a household was too poor to keep a servant, the wife bore an immense burden: tending the kitchen garden and caring for the domestic animals in addition to other domestic responsibilities. Those responsibilities included hauling water, lighting the stove, preserving and preparing food, clothing the family, and bearing and looking after children. The first ordinarily arrived within a year of the wedding, the rest regularly thereafter—each time bringing risk to the mother’s life. Only a tiny fraction of infants survived.16 For wives, one of the benefits of living in a household that contained other adult women—mother, mother-in-law, sister(s)-in-law—was the additional pairs of female hands that might assume some of that burden, and for brides, the opportunity to refine the skills they had been acquiring since early childhood.

Wealth did not free a wife from domestic responsibilities. Instead, her duty became overseeing the servants who did the work, to ensure that they maintained appropriately high standards.17 The duties of a rural gentlewoman were at least as extensive, especially when her husband was away performing service. In his absence, she ordinarily assumed management of the family estate, which meant overseeing the labor of field serfs in addition to her strictly domestic responsibilities. Rural gentlewomen apparently enjoyed considerable independence.18

Nevertheless, by custom and by law—and whatever her economic or social status and however extensive her duties—a wife remained subject to the authority of her husband and was supposed unquestioningly to obey his commands. In a weakly governed polity such as early modern Russia (like much of Europe at the time), social stability itself depended on proper governance of the household. To ensure social order, husbands and fathers were expected to exert control over potentially unruly women and the young. To that end, both custom and law empowered the men to employ violence when they deemed it necessary, while ideally exercising judicious restraint. The Domostroi put the matter bluntly: “If your wife does not live according to this teaching and instruction . . . then the husband should punish his wife. Beat her when you are alone together, then forgive her and remonstrate with her. But when you beat her, do not do it in hatred, do not lose control. A husband must never get angry with his wife.” On disciplining children, the Domostroi offered more harsh advice still.19 Short of murder, Muscovite law offered no punishment for “domestic violence” (a term Muscovites would never have used). Even in the case of murder, the law made sharp gender distinctions.

The Law Code of 1649 reflected these distinctions. Among its many other purposes, the code represented the first effort by the Muscovite state to regulate intra-familial violence. The code stipulated that a husband who murdered his wife be flogged with the knout, just like other persons who committed a homicide. A wife who murdered her husband, by contrast, was subject to burial to the neck until death, whatever the circumstances that prompted her action. In practice, courts rarely imposed harsh punishments on men who murdered their wives, especially if courts deemed the death “accidental” and the wives, disobedient or adulterous—either of which...