History of Construction Cultures Volume 1

Proceedings of the 7th International Congress on Construction History (7ICCH 2021), July 12-16, 2021, Lisbon, Portugal

- 796 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

History of Construction Cultures Volume 1

Proceedings of the 7th International Congress on Construction History (7ICCH 2021), July 12-16, 2021, Lisbon, Portugal

About this book

History of Construction Cultures Volume 1 contains papers presented at the 7ICCH – Seventh International Congress on Construction History, held at the Lisbon School of Architecture, Portugal, from 12 to 16 July, 2021. The conference has been organized by the Lisbon School of Architecture (FAUL), NOVA School of Social Sciences and Humanities, the Portuguese Society for Construction History Studies and the University of the Azores. The contributions cover the wide interdisciplinary spectrum of Construction History and consist on the most recent advances in theory and practical case studies analysis, following themes such as: - epistemological issues; - building actors; - building materials; - building machines, tools and equipment; - construction processes; - building services and techniques; -structural theory and analysis; - political, social and economic aspects; - knowledge transfer and cultural translation of construction cultures. Furthermore, papers presented at thematic sessions aim at covering important problematics, historical periods and different regions of the globe, opening new directions for Construction History research. We are what we build and how we build; thus, the study of Construction History is now more than ever at the centre of current debates as to the shape of a sustainable future for humankind. Therefore, History of Construction Cultures is a critical and indispensable work to expand our understanding of the ways in which everyday building activities have been perceived and experienced in different cultures, from ancient times to our century and all over the world.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

Open session: Building actors

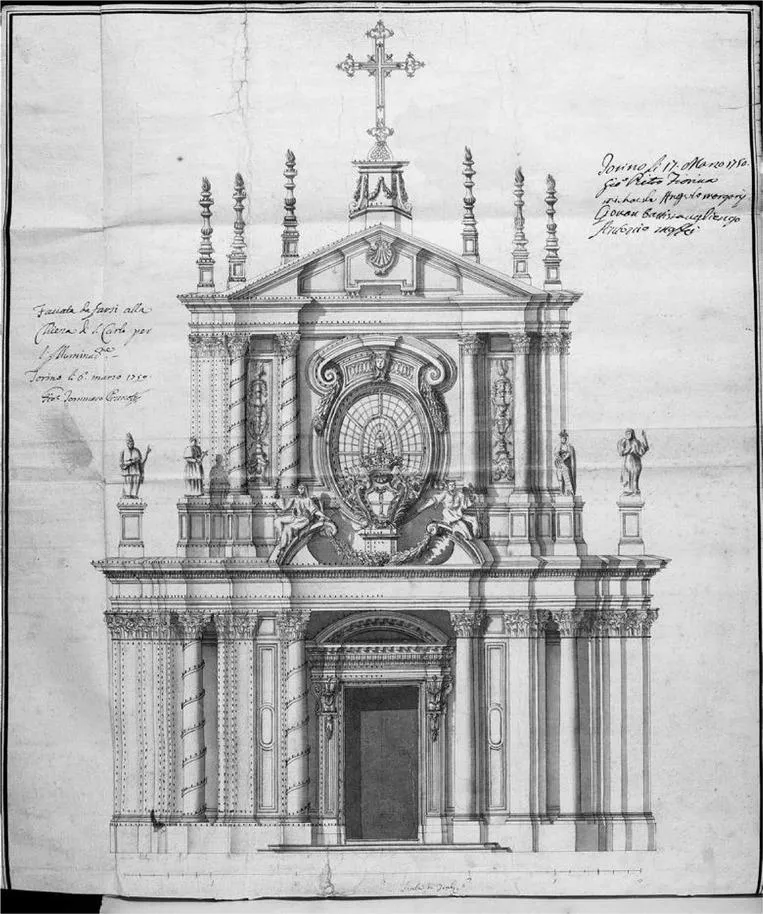

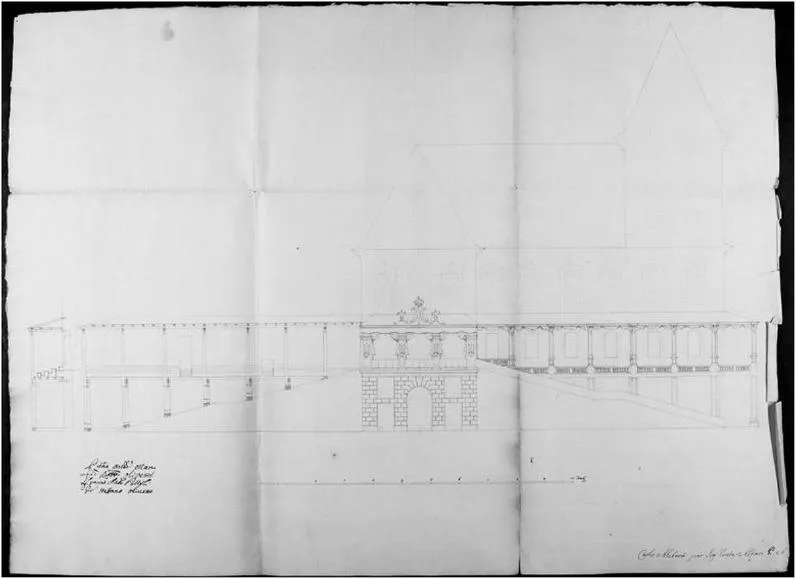

Building the ephemeral in Turin, capital of the Savoyard states

1 Building the Ephemeral in Turin

1.1 Ceremonies in the age of absolutism

2 The Construction Site of Festivities in Turin

2.1 The illumination

2.2 Ephemeral for the Valentino Reale

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of contents

- Introduction: History of Construction Cultures

- Committees

- Organizing and supporting institutions

- Open session: Cultural translation of construction cultures

- Thematic session: Form with no formwork (vault construction with reduced formwork)

- Thematic session: Understanding the culture of building expertise in situations of uncertainty (Middle Age-Modern times)

- Thematic session: Historical timber constructions between regional tradition and supra-regional influences

- Thematic session: Historicizing material properties: Between technological and cultural history

- Thematic session: South-South cooperation and non-alignment in the construction world, 1950–1980s

- Thematic session: Construction cultures of the recent past. Building materials and building techniques 1950–2000

- Thematic session: Hypar concrete shells. A structural, geometric and constructive revolution in the mid-20th century

- Thematic session: Can Engineering culture be improved by Construction History?

- Open session: The discipline of Construction History

- Open session: Building actors

- Open session: Building materials: Their history, extraction, transformation and manipulation

- Open session: Building machines, tools and equipment

- Thematic sessions

- Author index