- 304 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

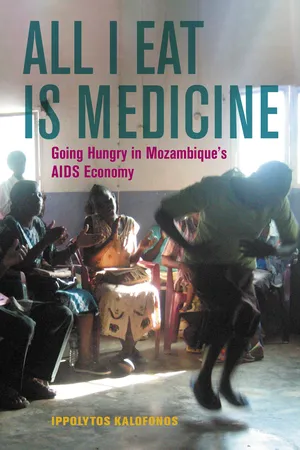

All I Eat Is Medicine charts the lives of individuals and the operation of institutions in the thick of the AIDS epidemic in Mozambique during the global scale-up of treatment for HIV/AIDS at the turn of the twenty-first century. Even as the AIDS treatment scale-up saved lives, it perpetuated the exploitation and exclusion that was implicated in the propagation of the epidemic in the first place. This book calls attention to the global social commitments and responsibilities that a truly therapeutic global health requires.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1 Estamos Juntos?

THE POLITICS OF HEALTH AND SURVIVAL IN MOZAMBIQUE

Popular understandings of global health and humanitarian intervention often imagine a technology, a treatment, or a form of knowledge traveling from the global north, where it was created and is common, to a tabula rasa, or blank slate, in the global south, where the essential technology neatly fills a preexisting need.1 In reality, long-standing infrastructures and histories powerfully influence the course of contemporary interventions. An understanding of the way AIDS treatment interventions circulated through and reshaped moral and political economies of care in central Mozambique requires a familiarity with the sedimented histories of care that constitute the terrain upon which the interventions unfolded and that people with HIV/AIDS navigated. Political power, healing, and social belonging are interrelated in Mozambique, where healing is a social and political expression of inclusion and value. The struggle for health has also been a struggle for subsistence, as hunger has played a prominent role in Mozambican history, both as a crisis of survival and an idiom of power. This history of healing as a social and political project provides an important context for understanding contemporary dynamics and discourse around health, hunger, and power in the AIDS economy.

PRECOLONIAL CENTRAL MOZAMBIQUE

Archaeological evidence and oral tradition indicate that successive Bantu migrations from the Limpopo Valley in the south established sedentary communities in unoccupied territories and displaced or absorbed nomadic bands of hunters and gatherers in the Zimbabwean plateau roughly two thousand years ago.2 Early groups developed iron-smelting techniques that were used to make hoes for intensive cultivation, and from 850 to 1500 this region was dominated by states that engaged in agricultural activity and raised cattle. They also extracted surface gold and harvested ivory from the local elephant population. The Limpopo and Zambezi Rivers connected wealthy gold-producing regions in the interior to coastal trading networks, and largely autonomous towns along the caravan routes traded with extensive networks of Muslim merchants on the eastern coast of Africa from at least 900.3 Trade networks may have linked this region to the Mediterranean and Asia as far back as 690.4

The well-being of the community was integral to political legitimacy, and local rulers, although not divine themselves, had religious authority, as well as important economic and social responsibilities, as the owners and spiritual guardians of the land. Political power was thus tied to agricultural productivity and the ruler’s ability to feed his people.5 To ensure the health of the people and livestock and the fertility of the fields, the ruler consulted with n’angas, who embodied the ancestral spirits to whom the ruler appealed for rain.6 The divination of n’angas was also sought regarding the future possibility of war or famine. These vadzimu were the intermediaries between the physical world and a high god. Elaborate religious institutions and rituals reinforced the ruler’s position. The health of the community was seen as representing a balance between the natural and spiritual worlds, which intermingled in the daily lives of those in the community. This long-standing entwining of economic, moral, therapeutic, and political power rendered individual and community well-being inseparable from the fertility of the land and livestock and relations with others, including ancestors.

PORTUGUESE COLONIALISM: A POLITICAL ECONOMY OF EXTRACTION

While the Portuguese were initially attracted to the gold and ivory of the African interior, the Indian Ocean location was the linchpin in the global expansion to India and the spice islands of the Portuguese empire. Rather than conquer and control, the Portuguese adapted to local patterns of power and production and in many cases depended on the favor of more powerful local rulers, to whom they paid tribute. But in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the “Scramble for Africa” increased the intensity of European colonization, channeling Africa’s riches into the world economy. Portugal’s colonial project in central Mozambique was outsourced to a private concession funded with international capital, the Mozambique Company, which would rule Manica Province from 1890 to 1941. The company used police power to extract taxes and labor for settler plantations and infrastructure projects, purchased agricultural products at depressed prices, and exported African labor to neighboring colonies in exchange for payment. The Company “discarded any pretense of development and transformed its holdings into a massive labor reserve and tax farm from which the company’s European and African employees violently extracted peasant surplus.”7 Labor conditions were so aversive that even faced with food shortages, in 1909 people in one district said “they would prefer to eat roots and wild fruits than to [work in] Manica, where they should die.”8

A report filed in 1925 by American sociologist Edward Ross with the League of Nations’s Temporary Slaving Commission highlighted mounting international criticism. Ross quoted a missionary physician’s description of the precarious conditions peasants faced: “The chronic state of semi-starvation, in which the majority of people now exist, I attribute to the excessive demands made for labor, leaving insufficient time for the cultivation of their crops.” One group of workers told Ross they were “slaves of the Mozambique Company.”9 Regimes of forced labor were continued and refined by the Portuguese administration even after the Mozambique Company’s contract expired in 1941.10 Household labor was diverted from subsistence-level activities to cotton production (demanded for trade and as payment for taxes by Portuguese authorities) to such a degree that food shortages were created. A 1941 survey from the Gaza province in the Limpopo region concluded that “50 percent of the women could not produce the forced cultures without seriously reducing food production.”11 In response to this crisis, cultivation shifted from grain to manioc, which is drought resistant and requires little attention but is significantly less nutritious. Famines were common in the 1940s and 1950s, and a 1959 government report acknowledged: “The majority of the population is underfed,” warning that “it is absolutely necessary that cotton producers have sufficient food to enable them to work.”12 The few existing sources of data from hospitals and rural clinics indicate that nutritional diseases, such as kwashiorkor, rickets, scurvy, beriberi, and pellagra, were common.13

STRUGGLES FOR SURVIVAL

As colonial conquest created crises of health and survival, prominent n’angas responded to safeguard the health and well-being of their communities. Religious leaders and healers helped to legitimize, organize, and coordinate rebellions, uniting public opinion behind uprisings and offering divine sanction and ritual approval of secular leadership.14 In one uprising in 1902 in Báruè, just northeast of contemporary Chimoio, n’angas claimed to have secret medicines that would turn Portuguese bullets into water.15

While the Portuguese relationship with indigenous medicine had been characterized by “mutual borrowings for practical healing purposes,” the formalization and consolidation of colonial rule in the late nineteenth century marked a change.16 Colonial biomedicine was deployed as a tool of influence and control over the local population and as propaganda to justify the colonial project internationally.17 The Portuguese, like other colonial powers, repressed and ruptured local forms of power and knowledge—particularly those of n’angas—as these were perceived as threats to colonial authority.18 Laws were passed against rituals of possession, divination, exorcism, and spiritual healing. Practices related to these activities—drumming, dancing, singing, and prayers directed toward ancestral spirits—were banned as witchcraft. Indigenous healing was relegated to an archaic and irrational African past that was demonized by Christian missions as well as the Portuguese colonial administration. Those caught practicing were imprisoned, sentenced to forced labor, or exiled.19 Indigenous social and political institutions were co-opted, attacked, and driven underground.

With indigenous healing outlawed, colonial biomedicine took over in countering perceived health threats, predominantly infectious, posed by the native population, with the overarching goal of preserving the labor force and protecting European settlers. The health measures most likely to be experienced by native Mozambicans were restrictions on movement in the name of epidemic containment and forced vaccination and hospitalization.20 Colonial biomedicine and public health were largely experienced as additional forms of oppression.21 In Manica and Sofala, the Mozambique Company provided rudimentary health services for its workers. Regarding treatment in the Manica hospital, the company’s inspector general noted that “our natives have in some cases been shockingly treated.”22 The director of the native labor department acknowledged that “the native has great repugnance for being treated by whites and much more so for entering the hospital, because they think that once they enter that place they’ll never leave. . . . Perhaps there is some logic in their actions because if sometimes they receive good care, at others it leaves a little to be desired.”23 There was no safety net provided for the majority of Mozambicans, and traditional and historical institutions of social cohesion based on agriculture, kinship, and veneration of ancestors were repressed and actively persecuted.24 Healing was severed from the political order as forms of public healing were driven underground and local clusters of kin had to organize and pay for their own health care in secret within a more circumscribed, private sphere.25

As did many African colonies, Mozambique had a bifurcated legal system, called the Indigenato.26 The Indigenato defined the difference between settler citizen, or civilizado, and native subject, indígena.27 It was a form of institutional segregation marked by racial difference.28 The civilizado had full Portuguese citizenship rights and lived under metropolitan civil law, while the indígena would live under African law and the particular laws of the individual colonies. This distinction justified coercive labor exploitation and the suppression of native institutions and healing practices in the name of the colonial civilizing mission. Natives could attain the status of the assimilated person (assimilado). This third category granted exemption from forced labor as well as some of the benefits of citizenship, though not political participation. It applied to Mozambican and Asian artisans, traders, skilled workers, and long-term urban residents who were able to “civilize themselves,” abandon “tribal customs,” and live as the settlers did, including converting to Catholicism. The assimilado status was also available to those of Asian or mixed racial background. The Indigenato shaped a series of ideological oppositions between native and citizen, traditional and modern, black and white, and rural and urban that endure in contemporary Mozambique and that permeate the logics of HIV/AIDS interventions.

Though the Portuguese justified their colonial presence as first a “civilizing” and then a “modernizing” mission, few Mozambicans ever enjoyed the more powerful political subjectivity of...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Maps

- Introduction: A Doença do Século (The Disease of the Century)

- 1. Estamos Juntos? The Politics of Health and Survival in Mozambique

- 2. The Emergence of the AIDS Economy

- 3. Therapeutic Congregations: Associations of People Living with HIV/AIDS

- 4. “We Can’t Find This Spirit of Help”: The Uses of Community Labor

- 5. Being Seen in the Day Hospital

- 6. Hunger as Embodied Critique

- Acknowledgments

- Glossary

- Notes

- References

- Index

- Complete Series List

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access All I Eat Is Medicine by Ippolytos Kalofonos in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & AIDS & HIV. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.