eBook - ePub

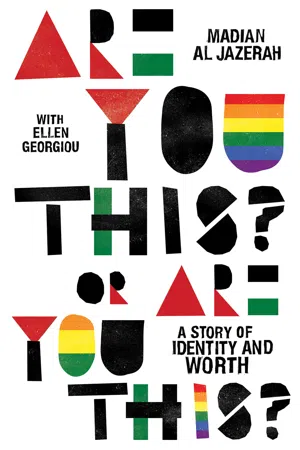

Are You This? Or Are You This?

A Story of Identity and Worth

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

When Madian Al Jazerah came out to his Arab parents, his mother had one question. 'Are you this?' she asked, cupping her hand. 'Or are you this?' she motioned with a poking finger. If you're the poker, she said, you aren't a homosexual.

For Madian, this opposition reveals not who he is, but patriarchy, power, and society's efforts to fit us into neat boxes. He is Palestinian, but wasn't raised in Palestine. He is Kuwaiti-born, but not Kuwaiti. He's British-educated, but not a Westerner. He's a Muslim, but can't embrace the Islam of today. He's a gay man, out of the closet but still living in the shadows: he has left Jordan, his home, three times in fear of his life.

Madian has searched for acceptance and belonging around the world, joining new communities in San Francisco, New York, Hawaii and Tunisia, yet always finding himself pulled back to Amman. This frank and moving memoir narrates his battles with adversity, racism and homophobia, and a rich life lived with humour, dignity and grace.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Are You This? Or Are You This? by Madian Al Jazerah,Ellen Georgiou in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Islamic Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART ONE

I

ARE YOU THIS? OR ARE YOU THIS?

Mama came to New York to visit me after we had not spoken for weeks. We are a close-knit family, a tribe, taught from the earliest age that you never go to sleep mad. As young children, we would go into each other’s rooms to hug it out before bed. Mama and I could not have survived the silence much longer. I had come out to her and Baba a few months earlier, and it had not gone well.

She arrived in the early afternoon. I went to meet her at LaGuardia airport and we took a cab and travelled in silence to a gay bar in Chelsea. I’m not sure what possessed me to take my mother to a gay bar. I think it was defiance. I came to New York after fleeing Amman because of my sexuality, and because I had had enough of Amman making me feel like dirt. Now I was saying, ‘This, Mama, is who I am.’

Luckily it was quiet, and she had absolutely no interest in her surroundings. She was calm and—true to her style—very composed. When she finally did speak, her only question was, ‘Can you explain this to me?’

‘Can I explain what, Mama?’

‘This thing. The thing you think you are.’

I tried to ‘explain’ being a homosexual without mentioning sex. It wasn’t easy and I was fumbling. She wasn’t even listening. She was distracted, fidgety.

Finally, I said, ‘Mama, what’s wrong? What’s on your mind?’

She took a long, deep breath. Looking around, she closed one hand to indicate a hole, while extending the index finger of her other hand and making a poking motion towards the hole.

‘Are you this?’ she asked, raising her closed hand. ‘Or are you this?’ she said, while poking with the index finger of her other hand.

I gulped my drink and stared at her.

‘Mama, it’s not about that. It’s not about that at all. You have to understand being gay is not just about sex. Just like you love Baba, I am looking for someone to love.’

She said nothing. I had two more drinks and we sat in silence. She was squinting and thinking hard. I knew she had more to say.

‘Mama, what is it?’

Again, a slow, deep breath.

‘Habibi, if you are this,’ and the index finger came out, poking a little more furiously than the first time, ‘then it’s OK. You can get married. You can marry a lesbian.’

I gasped and fell back in my seat.

‘Mama, why on earth would I want to marry a lesbian?’

‘And you can have a baby… there are plenty of Palestinian lesbians that would love to have a baby with you,’ she said, on authority.

Initially, I had thought that my mother’s issue with my sexuality was fear of what people would say and of disgracing the family. There’s certainly a little of that, but I realise now that it’s about her idea of normalcy. Mama wants me to have a ‘normal’ life. And as long as I am ‘this’ (index finger extended), then there is nothing to worry about—I am still a man.

Mama is not closed-minded. She was a teacher, and her sisters were also teachers. They wrote academic books on history, language and geography. Their names are still in books used for teaching across the Arab world.

Mama is also a true matriarch and a class act. Not only does she command respect—she demands it. She is the youngest of five sisters, all born in Palestine. They were all strong, educated, dynamic, stylish women, who set the stage for us in how we saw women. I couldn’t, therefore, comprehend how she could have such a limited view about homosexuality. It upset me and consumed me.

* * *

The conversation came up again two years later when I was living in Amman. My two aunties were visiting, always a big occasion in our household, and we were all together in Mama’s salon having ma’moul cake and tea. Auntie Qut was the religious auntie, who seemed to have a direct line to God whenever she disapproved of something we did. She was conservative but also had a fun, playful side. Auntie Aden was the modern auntie. She was cosmopolitan and liberal and always supported us in anything we chose to do. They could not have been more different from each other, and they were always in complete disagreement, but on this occasion, they were very much on the same page. They wanted to talk about me and my sexuality, right here, right now, in Mama’s salon. It was an obvious set-up.

They started talking about homosexuality in general terms, as if it was a usual topic of conversation at afternoon tea in Amman; as if they were experts on gayness, lesbianism and sex; and as if I wasn’t there. I could see where this was going.

Auntie Aden said, ‘There is nothing in our religion that talks about this or condemns this. You know this, right?’ And she looked straight at my mother.

‘Not in the Quran?’ asked my mother.

‘No. There is nothing against homosexuality,’ said Auntie Aden knowingly. ‘Absolutely nothing. There is nothing in the Quran.’

‘What about Lot and his tribe?’ asked my mother.

‘No,’ said Auntie Qut, shaking her head. ‘Anyone who has studied the Quranic narrative knows how ambiguous that story is.’

‘What about Sodom and Gomorrah?’ my mother went on.

‘No, no,’ said Auntie Qut with certainty. ‘The Sodom and Gomorrah story is not about homosexuality at all. Theologians dispute it every day.’

Auntie Qut gave me a self-satisfied, reassuring smile. She was suddenly an authority on homosexuality and world religions.

Meanwhile, I sat quietly eating cake and sipping tea, fearing the worst.

Auntie Aden turned to Mama and said, ‘Why are you so bothered about this? Don’t you remember Shukri? And what about our distant cousin Jamil?’ And she began throwing out names of apparently gay men they had known growing up.

They weren’t called gay, of course; they were called mish naf’een, ‘useless’, ‘underperformers’. They couldn’t perform sex with a woman, so they were ‘less than’, but they were, apparently, fully accepted by society.

It was definitely a conversation for my benefit and the aunties obviously had my back, but I was dying. I think about it now and I still feel shame.

My mother was suddenly emboldened and moved forward in her seat to face me. She looked me in the eye and asked me again: ‘But I don’t understand, Madian. Are you this, or are you this?’ And, again, one hand was cupped, and the other was poking with an extended finger.

It was still bugging her.

‘Why is that even important?’ exclaimed Auntie Aden as she glared at my mother.

‘Well,’ said my mother indignantly as she fell back in her chair, ‘if he can poke, he’s a man.’

* * *

‘Are you this, or are you this?’ is not, of course, limited to that conversation in that salon in Amman. My mother was expressing a widely held opinion, especially in the Arab world. To be the poker is OK. We can live with that, no harm done. You’re not a homosexual—you’re off the hook. It is the receiver who is the homosexual. If I am the penetrator, I still have value. If I am penetrated, however, I am devalued. Of course, Mama wanted me to have value.

‘This’, and I extend a finger, is about domination and power. It means man over woman. It’s about sexism, hierarchy and patriarchy. Moreover, the poker is never at fault. It doesn’t matter where he puts ‘it’; he’s always a man.

In the Arab world, homosexual men are men who like to be penetrated. They and transgender women are called mokhannatheen, which means ‘acting like women’.

I have given workshops through the United Nations to address issues facing the LGBTQI community in the Arab world. I have talked about how transgender men are more accepted in Arab societies than transgender women, because they are seen as females who want to be men, thereby adding value to themselves. A trans woman, however, is moving down in social value by expressing her womanhood. In fact, she has no value.

Though I don’t talk about myself, ‘Are you this, or are you this?’ is at the core of every talk I give. And yes, I use my mother’s hand gestures. If you receive ‘this’ shame on you, you are a disgrace, and you deserve everything that comes with it. ‘This’, however—my extended finger—is the ultimate weapon.

In many cases the first thing a prison guard does to a prisoner is sodomise him. To devalue him. Emasculate him. It happens all over the world. You only have to look at the photos that came out of Abu Ghraib prison during the Iraq War to see how US troops used sodomy as a weapon of war. It is the ultimate humiliation.

I saw from an early age that this humiliation rarely applies to the penetrator.

We grew up in a compound in Kuwait that housed employees of AMINOIL, the American Independent Oil Company. It was an exclusive community—beautiful homes, a country club, pools, children on their bikes, a small supermarket selling mainly British and American food items.

There were two apartment buildings not connected to the compound. A group of teens from these apartments would hang out with my older brothers and others from our compound. They were the cool guys and there was an obvious leader. He was charismatic, good-looking and brash.

One day there was a huge ruckus and lots of jeering and laughter. We all ran over to see what was going on.

The group was goading and applauding the leader because he had apparently had sex with a donkey. They were not ridiculing him—they were cheering him on. Patting him on the back. Praising him. He was a man, so much so that he had even fucked a donkey.

I knew what was going on and the image stuck. It’s something I’ve talked about over the years. This disgusting act was not criticised or ridiculed by his peers. Yes, it was an act of bravado and stupidity, but it never made him less valued as a man.

Bestiality is, of course, not condoned in the Arab world. But there are always jokes and innuendo, and it is generally known that if you have sex with an animal, such as a goat, you have to kill it. You can’t possibly eat it—it’s impure, it’s not halal. Such a concept could not even exist if there was not an accepted belief that people do, in fact, fornicate with animals. And again, the penetrator is never at fault. It’s the animal that has to be killed.

This, too, applies to ‘Are you this, or are you this?’ If you are a poker, it doesn’t matter even if you’re penetrating an animal. You are a man. Doing the manly thing. The poker is always off the hook.

So when my mother asks the question, she is hoping beyond hope that I’m a poker. No honour lost. It never crosses her mind that I could be both.

Sadly, I don’t talk to Mama about my relationships. A whole part of my life is still in the shade and things go unsaid. She has accepted me as her son, no matter what, but she has never accepted my sexuality. I used to get a lot of hugs from Mama. I love her like no other being on this earth. I’ve never felt she has stopped loving me, but the hugs stopped a long time ago.

II

ALL NAMES BEGIN WITH M

My mother, Marwa, was born in Jenin, a Palestinian city in the West Bank. She grew up in a household where matriarchy was the core, but patriarchy was an invisible cloak everyone wore.

Her mother, Mariam, was a sheikha—a noblewoman—and was highly respected in all of Jenin. My grandmother was strong, independent and assertive, but she didn’t produce a male heir, and so she was still seen as ‘less than’.

While she was ‘this’—a respected leader in her community, a dutiful wife and a good mother, who ran a house of integrity, she was also ‘this’—a failure, because she didn’t produce a male child. Because of this failure, she had to accept her husband taking a second wife.

My grandmother was born into a wealthy family with a huge estate in Beesan—land which is today occupied by Israel. When she married my grandfather, Nayef, they settled in Jenin, where she became well known as a formidable, though generous, sheikha. She would keep gold coins tucked into her headdress, and if anyone asked for help, or if she saw need, she would pull out a coin. People would say, ‘Mariam’s headdress is always ready to provide relief.’

Her breast milk was also sought after because it was noble milk. Mothers would often bring their newborns to her to feed, since her milk was said to bless babies with health and intelligence.

I never met my grandmother, but her five daughters—my mother and her sisters—have DNA charged with strength and dignity.

There was, however, no male heir, and this was a problem.

My grandmother did give birth to a boy after the youngest girl, my mother, was born. But he died as a baby. My mother heard whisperings: ‘What a tragedy. Why did the male child have to die? Why couldn’t the youngest daughter be taken instead?’

As the years passed, it became clear that my gran...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Part One

- Part Two

- Acknowledgements