1Presentism, Politicization of History, and the New Role of the Historian in Russia

Ivan Kurilla

THE ACADEMIC STUDY of history and common views on its relevance to the present are rapidly changing. This evolution has been marked by the growing number of actors engaged in history politics; heightened attention to the traumatic history of the previous century, underlined by cultural and political agendas; and the emergence of a burgeoning new discipline, memory studies. French historian Francois Hartog has linked the emergence of memory studies to the phenomenon of presentism—the cultural context, or “regime of historicity,” that makes the present virtually dominate over both past and future.1 Within the existing analyses of the relationship between history and memory, I emphasize the significance of the recent past on memory; many of the traumas considered in memory studies deal with the experience of the last three or four generations—a typical generational horizon of the traditional “ahistorical” society.2

Presentism is in part a result of the inability of any given society to cope with its painful past, to establish a distance between now and then, especially when then refers to mass murder. The traumatic experience continues into the present without ever becoming past. Societies trapped in the unprocessed memory of twentieth-century violence cannot establish distance from that time and lose a sense of historical progression, which, in its turn, hinders the “vector of progress.”3

The Russian case both illustrates this particular perspective on the past and helps historians better understand the general challenges facing all countries.4 In Russia, presentism is aptly characterized by the intensified struggle over history among different actors within the politics of history: the state, business elites, professional historians, and, most recently, grassroots and family-oriented organizations.

Among the groups claiming their right to control historical narratives are various supranational actors united on an ethnic or geographic basis, for-profit history-related businesses, and professional historians. These cleavages contribute to the international “history wars” fought between Russia and its neighbors.5 Institutionally, there are currently two state-controlled historical societies and an independent professional group in Russia. However, the field of memory has also been shaped by recent grassroots initiatives at local and family levels. The battleground has increasingly shifted into new domains and includes building monuments, demarcating holidays, changing city and street names, rewriting history textbooks, and establishing master narratives.

I differentiate between the political use of history and the business of history, although they overlap at times. Thus, governors and mayors use the historical significance of their respective administrative units not only to attract tourists but also to claim additional funds from the federal budget—for example, to celebrate a city’s jubilee (confusingly, in 1977, Kazan celebrated eight hundred years since its foundation and, in 2005, one thousand years). In 2010, Volgograd governor Anatolii Brovko demanded adoption of a special all-Russian program of patriotic upbringing that would require every high school student to visit Volgograd, formerly Stalingrad, known as the patriotic capital of the country.

Historian Alexei Miller, who studied these processes for many years, suggested differentiating among the “politicization of history” as the “inevitable and unescapable” impact of a political agenda on professional historians and all those interested in history, “memory politics” as a body of “social practices and norms regulating collective memory,” and “historical policy” as choosing one interpretation of history over others for political reasons as well as attempts to “convince the public that the interpretation is correct.”6 To my mind, this terminology does not take into account the social aspect. Besides, “memory politics” incorporate norms and practices that diffuse the border between “memory politics” and “historical policy.” I tend to agree with Nikolay Koposov, who divides historical memory into “cultural memory” linked to the “legacy industry” and “political memory” supported by institutes of “historical policy.”7

Using this conceptual framework, this chapter examines the changing role of historians in circumstances determined by the rise of presentism and current politics, as well as a new reality shaped through the entry of new actors into history politics.

State Appropriates History for Political Purposes

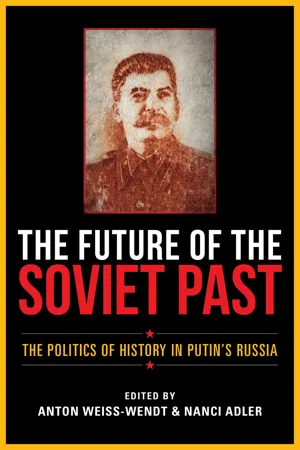

History used to be a major ideological discipline in the USSR. Joseph Stalin’s Short Course of the History of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) was a one-volume exposé of the dominant ideology that included everything the Soviet citizen needed to know about politics and society. Stalin’s death did not alter the situation; indeed, his successors had to deal with his legacy adding complexity to the canonic vision of the past. During Nikita Khrushchev’s Thaw and Mikhail Gorbachev’s perestroika, revelations about mass crimes committed under Stalin’s rule made politicians even more committed to reforms, thus making the debate about the past a vital part of politics.

The collapse of the USSR was at the same time a failure of Marxism. Among other things, however, the ruling ideology also shaped historical methodology. The critique of Marxism, by initially incorporating the history politics of the Soviet regime, inadvertently demolished part of academic history and drastically altered the landscape of memory.

During the 1990s, history practically disappeared from public debate in Russia. Social reformers no longer needed the past to justify their policies, and the globalizing economy appeared to reject national histories. The first decade after the collapse of Communism focused on the future, not on the painful or heroic past. (Russian intellectuals’ tradition of comparing the Russian experience to the German one rested on an insufficient knowledge of the German story.)8 However, since the language of politics has been distorted by its arbitrary use in the 1990s (e.g., liberal and democratic have become the name of a populist right-wing party led by Vladimir Zhirinovskii), political identities in Russia tend to be defined in historical terms. Today, the best way to understand the political outlook of ordinary Russians is to ask them about their attitude toward historical figures such as Stalin or Peter the Great or historical events such as the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 or the unraveling of the Soviet Union in 1991. The transformation of the language of historians into the language of politicians did not attract much attention at first, but eventually it came to negatively affect the academic field of history as society began to perceive any public statement with reference to history as a political one.9

After a decade marked by crisis in Russia’s attitude toward its past, the new government of Vladimir Putin began a process of consolidating the nation’s past in order to establish Russia firmly in the present. It also gradually reclaimed control over the historical domain as the main source of ideology, propaganda, and national identity.

More than anything else, the history of the Second World War has been (re)politicized in Russia since 2000. It remains the focal point of Russian history. The Great Patriotic War constitutes the core historical memory for Russians and hence endows it with great symbolism. This is eagerly exploited by politicians, who describe the Soviet victory over Nazi Germany—which most Russians consider the country’s highest achievement—in a terms that had been adopted in Leonid Brezhnev’s USSR. The victory narrative has ossified, and any attempt to challenge it even marginally meets political rebuttal.10 In recent years, however, this narrative has acquired new characteristics, including an anti-Western tone and an emphasis on the great organizing capacity of the state.

Notably, in the history promoted by Russian politicians, victory in the war is much more significant than the plight of the population during those years and the sky-high death toll (typically mentioned only in passing). In 2010, when Volgograd governor Anatolii Brovko sought a federally funded center of patriotic education in Volgograd (as mentioned earlier), the project was named Victory Center despite the common knowledge that the memory of the Battle of Stalingrad includes not only celebration but also mourning. The generic image of the “Stalingrad victory,” with no reference to suffering and death, has been clearly selected for political purposes.11

“Victory” is a core element politicians want to see in each and every period of Russian history. It is rather symptomatic that the chair of the academic council of the Russian Military Historical Society, Vladimir Churov, insisted during the preparations for the commemoration of the First World War that Russia should “participate in a parade of the victorious nations.”12 In that particular case, the First World War was refashioned in accordance with the official Russian narrative of the Second World War.

The Russian state uses various methods to impose its vision of the Second World War and command historical interpretations: school textbooks, TV documentaries, museum exhibitions, legislation, and so on. Beginning in 2004, the government started regaining control over history textbooks. The first casualty was a textbook by Igor Dolutskii that challenged high school students by including a provocative assessment of Putin’s regime by two opposition figures. The Russian Ministry of Education struck the textbook from a recommended literature list, and it was eventually purged from the classroom.

In 2007, President Putin endorsed a different school textbook that provided students with the emerging “official” interpretation of recent Russian history. The main purpose of the textbook—History of Russia, 1945–2007, by Alexander Filippov, Alexander Danilov, and Anatolii Utkin—was to erase any harsh criticism of Russia’s twentieth-century ruling regimes.13 Critical assessments were “counterbalanced” by a list of positive achievements. Putin and his associates repeatedly insisted that raising a “patriot” requires teaching a heroic history of the country and that dark pages of the national past are not appropriate subjects for school textbooks. Many Russian historians and human rights activists have condemned this position and the new textbook. Others have been more cautious when stating that, while such a view (read: Putin’s) of Russian history is possible, the state’s prerogative in determining which version of history will be taught at school is problematic.

In early 2013, Putin returned to the problem of history textbooks, now suggesting the production of a “unified” textbook for schools that would replace the variety of texts available to teachers. He expressed concern over the existence of conflicting narratives of the past in various history textbooks published in Russian regions. The state response was in a sense predictable: it tried to expunge alternative narratives. However, it is common wisdom that contemporary society has space for multiple narratives and that the only way to address a controversy is to use analytical skills to examine conflicting views. Putin’s initiative has gone through many twists and turns to eventually produce a “historical-cultural template” and shorten the list of publishers permitted to publish new history textbooks.

Russian state-controlled television has been producing quasi-historical programs with a subtle political message. A prime example of this practice is a “documentary” entitled Death of an Empire, filmed by Father Tikhon (Shevkunov), an Orthodox priest and allegedly Putin’s spiritual counselor. Built on the comparison between medieval Byzantium and contemporary Russia, the hour-long film delivered the message that Russia should not place too much trust in the West. According to the film, it was this mistake—and not the Ottoman Turkish conquest—that destroyed the Byzantine Empire in the fifteenth century, the implication being that Russia in the twenty-first century should learn the same lesson. After the film aired in early 2008, the British Economist noted that “in the minds and language of the ex-spooks who dominate Russia, history is a powerful tool.”14 While controversial, the official Russian approach to history is not unique, and there was no di...