- 214 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

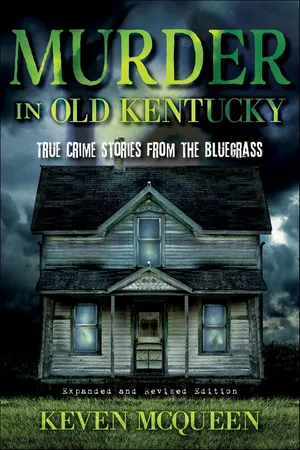

A true crime historian brings a light touch to the Bluegrass State's dark past in this revised edition with more stories of racing, bourbon, and murder.

In Murder in Old Kentucky, Keven McQueen recounts dark and disturbing tales from the pages of Kentucky history, including the 1825 murder of Col. Solomon Sharp—a sordid affair that inspired Edgar Allan Poe and Robert Penn Warren. He also examines the 1881 Ashland Tragedy, a heartbreaking murder of three innocent teenagers.

This revised and expanded edition features new cases, including: an arsonist who terrorized a family, massacring eleven of their relatives and burning the property of even more; a husband and wife found shot in each other's arms with a life-sized photo of another man between them; and many more deaths that made headlines.

Meticulously researched and written with Keven McQueen's trademark humor, Murder in Old Kentucky will captivate any fan of true crime or Kentucky history.

In Murder in Old Kentucky, Keven McQueen recounts dark and disturbing tales from the pages of Kentucky history, including the 1825 murder of Col. Solomon Sharp—a sordid affair that inspired Edgar Allan Poe and Robert Penn Warren. He also examines the 1881 Ashland Tragedy, a heartbreaking murder of three innocent teenagers.

This revised and expanded edition features new cases, including: an arsonist who terrorized a family, massacring eleven of their relatives and burning the property of even more; a husband and wife found shot in each other's arms with a life-sized photo of another man between them; and many more deaths that made headlines.

Meticulously researched and written with Keven McQueen's trademark humor, Murder in Old Kentucky will captivate any fan of true crime or Kentucky history.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Murder in Old Kentucky by Keven McQueen in PDF and/or ePUB format. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

eBook ISBN

9780253057501Subtopic

North American History1

KENTUCKY’S FIRST GREAT MURDER

THE BEAUCHAMP-SHARP AFFAIR OF 1825 WAS THE FIRST MURDER in Kentucky to leave a lasting impression on the general public and literary artists. Edgar Allan Poe’s only play, Politian (1835); William Gilmore Simms’s novel Charlemont and Beauchampe (1856); and Robert Penn Warren’s novel World Enough and Time (1950) all contain elements drawn from the crime. These days it might inspire an above-average TV movie of the week. The story includes a tragic romance and a bloody act of revenge born of a chivalrous instinct, and it ends with a hanging.

Col. Solomon Sharp, thirty-eight, was one of the most prominent men in Frankfort. President John Quincy Adams had called Sharp “the brainiest man that ever came over the Allegheny Mountains from the west.” Sharp had a brilliant political career, having served in the state legislature from 1809 to 1811 and in the US Congress from 1813 to 1817. His killer, Jeroboam Beauchamp (pronounced BEE-chum), was a twenty-three-year-old lawyer who had recently married. Beauchamp’s murder of Sharp was simply the fulfillment of a vow to his wife.

Beauchamp and Sharp first met around 1820, when Beauchamp was single and living in Glasgow, Barren County, Kentucky. Sharp hired the young lawyer to take care of some legal affairs. Beauchamp appears to have idolized Sharp, but for some reason, he quit his job after a while and moved back to his family’s home in Simpson County. Also in 1820, Sharp met the new neighbor, Ann Cook. Originally from Virginia, she and her mother had moved to Kentucky and were living with her brother near the Beauchamps’ farm. Accounts of her appearance vary. One version, probably derived from Beauchamp’s confession of his crime, says that she had a “slender but faultless form” and “pale but exquisitely chiseled features.” It also describes her as a “lovely girl,” though she was in her midthirties. On the other hand, author Richard Taylor describes her as “small, weighing about ninety pounds. . . . Her front teeth were gone. She was not very pretty and had a bad reputation.” (The unflattering information came from Dr. Leander Sharp, Solomon’s brother.) However she looked, soon after their acquaintance, Jeroboam and Ann were in love, although she was much older than he and had given birth to an illegitimate stillborn baby earlier that year.

In 1824, Solomon Sharp ran for the office of Kentucky’s attorney general. His political enemy, John U. Waring, in an attempt to discredit him, published a notice accusing Sharp of having been the father of Ann Cook’s stillborn child. Sharp won the election but at a humiliating cost to Ann Cook.

After a four-year courtship, Beauchamp asked Ann to marry him. She agreed on one condition: that he would promise to avenge the public embarrassment she had suffered because of Solomon Sharp. (Her condition implies that Sharp actually had been the father of her child. If the charge were false, it seems her ire would have been more properly directed at John U. Waring, the man who spread the scandal.) One account would have us believe that she told her young beau, “Avenge the wrong which I have suffered at the hands of Colonel Sharp. Never, never, until he expiates his offense through any means, shall this heart cease to know sorrow—aye, he must expiate it in blood and death, etc., etc.” However she requested it, Jeroboam agreed to take dire revenge against the colonel, and he and Ann were married in June 1824.

At first, Jeroboam, like Hamlet, did not seem eager to fulfill his promise of vengeance. Contrary to his later self-serving claims that he repeatedly attempted to challenge Sharp to a duel, the latter always finding a way to weasel out, Beauchamp went back to work for Sharp in Frankfort after the latter had been elected attorney general and all was peace and harmony between them—until fall 1825. Sharp wanted to be Speaker of the House in the Kentucky legislature rather than attorney general, so he ran for the office. His backers, remembering Waring’s canard from a few years before, wanted to neutralize it in case it came up again. Presumably with Sharp’s blessing, they published a handbill stating that Ann Cook’s illegitimate child had been half Black. At that time and place, nothing could have been considered a greater insult. Sharp won the election, but Ann had been humiliated all over again. Jeroboam talked the matter over with his wife and determined that nothing but bloodshed would restore her good name.

In early November 1825, Jeroboam armed himself with a dagger, kissed his wife goodbye, and commenced the four-day trip from Simpson County to Frankfort, murder on his mind every step of the way. When he reached the highway to Frankfort, he wore a bandana or handkerchief over his face, an attempt at disguise that only drew attention.

Jeroboam arrived in Frankfort on November 6, the day before the state legislature was to meet. Every hotel in town was filled to capacity, so he had to take lodging in the house of Robert Scott, ironically the man in charge of the state penitentiary. Late that night, Jeroboam sneaked out of Scott’s home—unfortunately for him, Scott heard him leaving—and walked to Colonel Sharp’s residence. On the way, he was spotted by the town’s night patrol, the members of which failed to fulfill their duty by sufficiently questioning him as to what he was doing out at such a late hour. Had they done so, Beauchamp’s foolish adventure might have ended there. The bungling of the law’s officers, then and later, plays a not inconsiderable role in the tragedy. Around 2:00 a.m., Beauchamp arrived at the home of the man he perceived to be his enemy. He took stock of the task at hand and noticed that the house’s side door adjoined a dark alley down which he could make a fleeting escape.

He knocked on the side door. No answer. He knocked again. The voice of Colonel Sharp issued from behind the door. “Who is there?”

“Your friend, John A. Covington,” answered Beauchamp.

(Many have wondered how Beauchamp came up with this name. Most likely he was confusing the names of Thomas A. Covington and John W. Covington, the latter an old friend of Sharp’s. Thomas A. was John W.’s brother.)

“I know no one by the name. Why have you come here so late?”

Taking advantage of the famous Kentucky hospitality, Beauchamp explained that all the hotels were full and asked if he could stay there for the night. The door opened and Solomon Sharp extended his hand in a gesture of friendliness. It was a gesture “John A. Covington” did not return. Sharp suddenly recognized the voice and realized who his visitor actually was. “Great God, it’s him!” he shouted.

Like a character in a bodice ripper, Beauchamp cried, “Die, you villain!” Drawing his dagger, he stabbed Sharp in the chest. So far, so good—but then Beauchamp’s plan fell apart. He looked up and saw Mrs. Sharp watching the gory scene. He had not counted on being seen by an eyewitness! Unsure of what to do, Beauchamp ran out of the house. As he did, an unnerving thought crossed his mind: Sharp had recognized his assailant. What if he told his wife before he died? Rather than escape down the dark alley as planned, Beauchamp stood outside the window to see if Sharp named his killer. To his relief, the colonel died without saying a word. Not so much to his relief, he realized that Mrs. Sharp was taking a good look at him through the window. He ran away, the screams of Mrs. Sharp echoing in the dark house behind him.

The assassination was the talk of Frankfort the next day. The legislature, Governor Desha, and friends of the colonel put up a $7,000 reward for the capture of Sharp’s killer. The clues were paltry: Mrs. Sharp said the murderer wore dark clothes, called himself John A. Covington, and had dropped a bloody bandana near one of the family’s rose bushes. Since Sharp was to have been named Speaker of the House of Representatives the very day he was slain, many thought the killing was politically motivated. Suspect number one was Sharp’s old enemy John U. Waring, but he had an airtight alibi: he had been shot in the hips just a few days previously and was confined to his bed far from Frankfort.

Poor Jeroboam Beauchamp was too naive to realize how quickly he would be suspected in the event of Sharp’s murder. People had not forgotten about his marriage to Ann Cook, and there was no doubt he had been in town that night. Robert Scott had rented him a room, the night patrol had encountered him near the Sharp residence, and witnesses had seen him riding out of Frankfort in the morning. That was good enough for the law. A posse was appointed to follow Beauchamp to Simpson County. On the way home, he visited relatives in Bloomfield, Bardstown, and Bowling Green. This was the opposite of shrewd, since it exponentially increased the number of witnesses who saw him on the road soon after Sharp’s murder. The mood was victorious when he arrived home to Ann. Still, the couple must have realized the precariousness of their situation since they made immediate plans to move to Missouri. The next day, the posse arrived and arrested Jeroboam. Despite his mild protestations of innocence, ere nightfall came he was being accompanied by four lawmen on the road to Frankfort.

One of the few physical clues incriminating Beauchamp was the bloody bandana found at the scene of the crime. The assassin noticed that one of the guards kept the cloth in his pocket, this being in the days before refrigerated evidence lockers. One night at a tavern, the guard drank too much and fell into a stupor. Jeroboam simply took the bandana from the sleeping guard’s pocket and threw it into a fireplace with the élan of a stage actor. Exit one piece of evidence. Despite this setback for the prosecution, there was impressive eyewitness testimony against Beauchamp, and the court set the murder trial for May 8, 1826.

Beauchamp clearly was in trouble. The chief witness against him was Mrs. Sharp, who had seen the murder and recognized Beauchamp’s voice. Patrick Darby, yet another enemy of Sharp’s—he appears to have cultivated political foes the same way other men collect stamps—had amassed considerable evidence against Beauchamp in order to clear his own name, including a letter Beauchamp had written to a neighbor beseeching him to come to Frankfort and lie on his behalf. In the face of such testimony, it took the jury only an hour to find Jeroboam Beauchamp guilty and recommend that he be hanged. The judge agreed and, after some haggling with Beauchamp, set the date for Friday, July 7, 1826.

Beauchamp decided to make the best of the situation by writing his confession—or, rather, two separate confessions, each intended for a different audience. In the words of Richard Taylor, “The first was for his uncle. The second was for the public. Many believed the first was the more truthful of the two. In the second, Jeroboam painted himself as the hero of a romantic drama. He hoped the Governor would read it and pardon him.”

The more creative confession spent its 137 pages depicting the late Colonel Sharp as the darkest villain this side of Beelzebub, a man “who sport[ed] with innocence” and deservedly lost his life for it. Eastern Kentucky University’s Special Collections and Archives department has a rare copy of Beauchamp’s confession, reprinted twenty-eight years after his death. It was my pleasure to peruse his one-sided purple prose one stormy morning. Anyone who reads it uncritically will wish he could have held Beauchamp’s hat for him as he did the stabbing. A sample line from the preface: “The death of Col. Sharp at my hands . . . will teach a certain class of heroes, who make their glory to consist in triumphs over the virtue and the happiness of worthy unfortunate orphan females, to pause sometimes in their mad career.” The embellished version did not sway the governor, but there were many who believed every word of it. In 1850, the National Police Gazette ran an article on the famous crime, relying heavily on Beauchamp’s version of events. It was widely reprinted, much to the annoyance of Sharp’s family. Several members wrote a letter to the Louisville Courier complaining that the article was libelous.

Now we move into the touching part of the story. Ann’s loyalty to her ill-fated young husband never flagged. She requested and received permission to stay with him in his subterranean jail cell. On the morning of the fatal Friday, July 7, the two somehow managed to sneak laudanum, a painkiller made of opium, into the jail cell and tried to poison themselves. All it did was make them sick. An hour before the hanging, Jeroboam and Ann settled on a backup plan: they would employ a knife he had smuggled into jail. (When we remember the incurious night watch and the deputy who slept as Beauchamp lifted the bloody bandana out of his pocket, it becomes clear that Frankfort had a serious problem with incompetent officers. In fact, Ann had dropped a blatant hint to the jailer about their plan two days earlier, when she requested that he find a shroud for her and a coffin large enough for two. He thought she was only kidding.) The guard was alarmed by the sound of groaning, and when he investigated, he found both husband and wife bleeding from self-inflicted wounds.

The dying Ann was taken to a private room. Jeroboam, feeble from loss of blood, was taken to see her. He held her hand as she died and said most Byronically, “Farewell, child of sorrow! Farewell, child of misfortune and persecution! You are now secure from the tongue of slander. For you I have lived; for you I die.” This sentiment was fine by the guards, who wanted to hurry up and hang Jeroboam before he bled to death too. They may have tended to drink and fall asleep while watching prisoners, and they seemed incapable of preventing contraband drugs and weapons from being smuggled into a tiny windowless cell, but they were not about to be accused of robbing the six thousand witnesses outside of a chance to see a hanging.

As drums rolled, Jeroboam Beauchamp was taken to a carriage and driven to the gallows on the outskirts of town. Beauchamp was so weak from blood loss by this time that he had to be supported by the jailer, but he waved at the ladies peering out of windows as his carriage passed by. When he saw the gallows, he complimented its solid construction—heaven knows, an unsafe gallows is a dangerous thing—and as final requests asked for a drink of water and for a fiddler to play “Bonaparte’s Retreat from Moscow.” When the sprightly number was over, he stood on the wagon. A hood was placed over his head to spare the dainty feelings of onlookers. The noose was placed around his neck, and a few moments later, Beauchamp no longer had to worry about bleeding to death.

Beauchamp’s father and uncle loaded his body, and that of Ann, into a wagon and drove to Maple Grove Cemetery in Bloomfield, Nelson County. The tragic couple was buried in the same coffin, his right arm around her neck. A state highway historical marker now denotes the cemetery where they are buried, and there can be few greater measures of fame. Philosophical persons and young lovers still come to reflect at the Beauchamps’ grave. The night before her death, Ann wrote an eight-stanza poem that reads in part: “Daughter of virtue moist thy tear, / This tomb of love and honor claim; / For thy defense the husband here, / Laid down in youth his life and fame.” The words are carved on the shared tombstone, commemorating their tragedy to the wondering world above.

2

RICHARD SHUCK CONFESSES ALL AND THEN SOME

RICHARD H. SHUCK IS LARGELY FORGOTTEN TODAY, BUT FOR A FEW weeks, he was probably the most famous man in Kentucky. His notoriety did not originate from anything positive but rather from a homicide he committed and the ghastly aftermath that resulted in the deaths of five men including himself.

Shuck was an unusually ham-fisted murderer. He was twenty-six years old and the son-in-law of Nelson Parrish, an elderly farmer who lived in the village of Gratz, near Owenton, Owen County. On the morning of Wednesday, July 26, 1876, not long after America’s centennial, Parrish and Shuck were seen strolling toward Parrish’s tobacco patch, which at that time of year likely would have been full of tall, luxurious plants—an ideal cover for evil activity. Neighbors heard the sound of a gunshot issuing from the vicinity. Within minutes, Shuck knocked on the door of his in-laws’ house, telling Mrs. Parrish, “The old man will never come back; he has gone to Henry County. I have bought his tobacco crop. Don’t keep any dinner, for we won’t be on hand.” Parrish had abandoned his wife temporarily in 1873, so her suspicions were not immediately raised by the lame and peculiar excuse for his absence.

Richard Shuck soon lived up to his reputation for not being terribly bright. Later that afternoon, he rode to Owenton, where he could not have drawn more attention to himself if he had walked around on stilts and worn a crimson sandwich board reading “I am a murderer.” Indeed, his actions are an encyclopedia of things one should not do after committing a homicide. He visited a saloon, where he had six drinks within twenty minutes and could not stop talking about how he had just bought old man Parrish’s tobacco, despite the fact that Parrish had recently sold most of his crop to a neighbor named Jack Johnson. Shuck boasted that he was carrying $150 in cash. A listener demanded that he repay an outstanding debt of ten dollars, since his financial situation was so flush. Shuck grudgingly attempted to pay the debt with a memorable counterfeit five-dollar bill marked by no fewer than twenty pinholes. The debtor refused to accept such a ratty-looking and obvious fake, so Shuck partially repaid him with three two-dollar bills. He continued spending money like a wild man and telling anyone who would listen about his purchase of Parrish’s tobacco crop.

Sometime during the night, Shuck sneaked out of Owenton and rode back to Gratz. He disposed of Parrish’s body, which he had stashed in some secret location the day before—he may have had help, as will be seen—and then returned to Owenton in the dead of night, hoping nobody noticed he had been gone. Despite this...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction to the Expanded 2021 Edition

- 1. Kentucky’s First Great Murder

- 2. Richard Shuck Confesses All and Then Some

- 3. A Mob Teaches Mr. Klein the Error of His Ways

- 4. Playing It Cool!

- 5. Colonel Buford Begs to Differ With Judge Elliott

- 6. An Argument for the Involuntary Commitment of the Criminally Insane

- 7. An Arsonist with a Grudge

- 8. Cold Case File, 1866

- 9. A Question of Sanity

- 10. The Hanging of John Vonderheide

- 11. A Regular Killing Machine

- 12. “A Little Fun”: The Ashland Tragedy

- 13. A Two-Fisted Professor Refuses to Take No for an Answer

- 14. Moses Caton, Family Man

- 15. Knox County Atrocity

- 16. A Possible Poisoner and a Definite One

- 17. The Smart Murders, or Choose Your Friends Wisely

- 18. How Not to Spend Homecoming Week

- 19. The Showers-Moore Tragedy

- 20. On the Benefits of Keeping One’s Temper

- 21. A Heart in the Wrong Place

- 22. Two for the Chair

- 23. Murder on a College Campus

- 24. Same Story, Different Endings

- 25. The Head on the Mound

- Bibliography

- About the Author