- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

How is it that, in the course of everyday life, people are drawn away from greenspace experiences that are often good for them? By attending to the apparently idle talk of those who are living them out, this book shows us why we should attend to the processes involved.

- Develops an original perspective on how greenspace benefits are promoted

- Shows how greenspace experiences can unsettle the practices of everyday life

- Draws on several years of field research and over 180 interviews

- Makes new links between geographies of nature and the study of social practices

- Uses a focus on social practices to reimagine the research interview

- Offers a wealth of suggestions for future researchers in this field

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Unsettling Outdoors by Russell Hitchings in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Environmental Science. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter One

A Wager and a Strategy

A Wager

If we want to understand the likelihood of future societies having regular beneficial contact with living greenspace, we should examine how outdoor experiences are handled by people in their everyday lives today. This is the first wager of this book. My suggestion is that, if we ignore how widespread social practices can serve to discourage people from a fuller engagement with the outdoors, a certain kind of environmental estrangement could become increasingly entrenched.

The Argument

This first chapter tells the story of how I came to make the above wager. It begins with some reasons for encouraging greenspace experience in everyday life. Then it considers why, despite the various benefits that have been linked to this experience, many people may be turning away from it. With that prospect in mind, I consider how a particular combination of concepts could shed a useful light on how this process is embodied. This chapter is therefore partly about existing studies of beneficial greenspace experience and how they handle the social trends that stand to shape the future of this experience. But it is also about how a particularset of ideas might help us to reconsider the challenges involved in tackling these trends. Here I am interested in how certain strategies for studying the relationship between humans and nature could be combined with a focus on how people are drawn into patterns of everyday living. The overall aim is to set the scene for a battle between the various apparent benefits of spending time with plants and trees and a series of commonplace social practices that could be separating people from them.

Greenspace as Home

Being near plants and trees appears to provide people with various benefits. One of the most arresting and influential studies to suggest this compared the recuperation rates of hospital patients with different views. The required information was already being collected by the hospital, but by looking at it with a fresh pair of eyes, Ulrich (1983) found that those patients who looked out onto areas of greenery recovered more quickly. Though this study couldn’t tell us too much about the mechanism involved, clearly there was something about seeing living vegetation through the windows of their wards that helped some patients to get better sooner. Another well-known study suggested this experience can also benefit those who are not yet ill. Moore (1981) found that prisoners with cells facing internal courtyards use medical facilities more often than those overlooking fields further beyond. So, being able to see greenery may prevent health problems as well as speeding recovery once they have been medically addressed. We have also seen how, for residents of city estates, being able to see trees and grass from their apartment windows appears to help them handle the various challenges they are facing in their lives and even reduce aggression levels (Kuo and Sullivan 2001). Other field tests have shown how contemplating vegetation can reduce blood pressure (Van den Berg, Hartig, and Staats 2007) and improve mood and self-esteem (Pretty et al. 2005). A recent study to build on what is now a fairly well-established tradition of identifying and enumerating the benefits that greenspaces can bring to people suggests that spending time in these spaces can reduce the cravings of those who are trying to overcome various addictions (Martin et al. 2019). These are just a few examples (see Keniger et al. 2013, for many more). The point, however, is that, if we allow ourselves to see humanity as a collective whose members continue to share the same essential attributes, there is a lot of evidence for the benefits of being around greenspace.

Why is this? One of the leading arguments is that being near to living vegetation provides a valuable form of psychological restoration (Kaplan and Kaplan 1989; Kaplan, Kaplan and Ryan 1998). The suggestion here is that simply looking at greenery can help people to mentally recharge themselves since contemplating the intricacies of vegetation can temporarily beguile us in a manner that allows us to transcend our immediate worries before returning to our tasks refreshed (Kaplan 1993; Han 2009). Another possibility is that this experience naturally neutralises the stressed feelings that many of us may otherwise increasingly harbour (Ulrich et al. 1991). Some even work with the assumption of a fundamental connection between humans, plants and trees such that our history of co-existence instinctively inclines people to seek out the reassuring familiarity of environments that contain living vegetation. This leads directly to the ‘biophilia’ hypothesis (Kellert and Wilson 1993), understood as the innate attraction to natural processes that humans may possess. The contention here is that dwelling within, and profiting from, certain living landscapes was fundamental to our development as a species. We should therefore be unsurprised to observe a positive response from people today. For example, some have explored how this filters through into a preference for looking at particular species of tree and how, within that, the trees that helped us to prosper in earlier evolutionary times are those that we still most like to see (Summit and Sommer 1999). We could take this to mean that a desire for greenspace experience is hardwired into humans. Either way, and regardless of whether we buy into this idea or not, these studies, when taken as a whole, suggest that people can benefit in all sorts of ways from exposure to these environments, if they are given the chance.1

Tempting People into Parks

What should be done with this knowledge? If we now consider how societies have most often thought about the right response to these findings, a common next step is to turn to the provision and design of public parks and gardens. This makes sense. If most of us now live in cities, if researchers know that being in and around greenspaces can benefit people, and if one of the tasks of good government is to ensure the inhabitants of a planet whose humans live increasingly urban lives have access to the services that are good for them, then city parks and gardens become an obvious focus for policy. In line with this argument, a lot of effort has gone into thinking about the forms of park provision that stand to produce the maximum social benefit. In doing so, effective landscape design and urban planning has come to seem like the obvious means of putting these ideas into practice. Indeed, the path between studies of greenspace experience and suggestions about what should be done with their findings is now fairly well trodden. And it commonly moves from an argument about benefits to an interest in the most effective means of designing and planning the most visually attractive and welcoming city greenspaces.2

Recent examples include a study in which Chinese citizens were shown urban scenes (from those with lots of concrete to those with more vegetation) in an attempt to identify how public greenspaces could be most effectively designed to reduce stress (Huang et al. 2020). Then there is a consideration of the value of features like colourful flowers based on how people in British parks and gardens respond to different pictures of plants (Hoyle, Hitchmough, and Jorgensen 2017). Another example is an exploration of the extent to which ‘actual’ or ‘perceived’ biodiversity in the greenspaces experienced by French residents impacts most positively on their wellbeing (Meyer-Grandbastien et al. 2020). A fourth study began by tinkering with images of various local cityscapes (adding vegetation to places where it is currently lacking) before seeing how Chileans responded to these pictures (Navarrete-Hernandez and Laffan 2019). The authors took such an approach based partly on the argument that, even though a great deal of work has focused on the visual experience of parks, many cities cannot boast these facilities. Their argument is consistent with the findings of Hartiget al. (2014), who note how parks have been the predominant focus when researchers have thought about what they should do with the suggestion that greenspaces promote public health.

But what if, for other reasons altogether, and which have comparatively little to do with effective greenspace provision and design, people are becoming disinclined to derive these benefits? What, for example, about broader processes of cultural change: the trends that gradually push us to live our lives in some ways instead of others and which, often without us necessarily noticing, are quietly shaping the future of greenspace experience? Scholars occasionally argue for the need to consider such broader sweeps of change. Grinde and Grindal Patil (2009), for example, pursue the contention that, though greenspace benefits appear to exist, we must still stay mindful of their ‘penetrance’. Their point is that we should not forget how various cultural factors may very well be over-riding their apparent draw. Hartig (1993) has similarly argued for studying greenspace experiences in a ‘transactional perspective’, namely alongside, rather than apart from, the broader processes that either push people towards or away from these experiences. His idea is that, though positive responses may be hardwired into humans, the likelihood of different groups seeking out the experiences that produce them is another matter. If spaces containing certain kinds of living vegetation are where we feel most at home, we might imagine that tempting people into such environments shouldn’t be so hard. Not so, according to some others.

The Extinction of Experience

Enter the ‘extinction of experience’ thesis. This is the idea that, despite the various apparent benefits of spending time in greenspace, many lives are increasingly decoupled from regular outdoor experiences with living vegetation, different forms of local animal life, and other natural features. According to Soga and Gaston (2016), fewer and fewer of those who live in modern societies are having enough contact with the natural world. This, according to Pyle (1993), the originator of the term ‘extinction of experience’, sets up a vicious circle of increased alienation from experiences that may very well be beneficial to us, but to which we could be increasingly indifferent – a cycle of growing disaffection that may well have, according to many of these researchers, some fairly disastrous consequences. Zooming out to contemplate the broader history of humankind, Kellert (2002, p. 118) goes as far as to argue that modern US society has ‘become so estranged’ from its natural origins, that it now fails to recognise its ‘basic dependence on nature as a condition of growth and development’. It’s easy to see the problem here. If many people no longer care about, or see themselves as part of, the wider ‘natural world’, humanity could very well be drifting towards a rude awakening, whilst (adding insult to injury) being comparatively unhappy along the way by virtue of how they are increasingly oblivious to the benefits that flow from greenspace experience.

This is an alarming prospect. And we should examine the processes involved before we abandon all hope. The leading villain in this story is often urbanisation. Despite the best efforts of some of the park planners and researchers discussed above, city living is often taken to draw people away from the likelihood of beneficial encounters with greenspace. If the vast majority of humans are now living urban lives, researchers should examine how everyday experience is structured in different cities around the world and see what that tells us about the likelihood of people venturing out into greenspaces (see, for example, Turner, Nakamura, and Dinetti 2004; Fuller and Gaston 2009). Another anxiety centres on how new recreational activities could be replacing outdoor play. The migration of social life online and the ways in which many children are coming to prefer computer games over outdoor activities has been a particular source of worry for some (Pergams and Zaradic 2006; Soga and Gaston 2016). Just how busy many people now are occasionally gets a mention – how it is that many groups, in cities at least, now feel themselves to be too rushed to think about ways of inserting more greenspace experience into their lives (Lin et al. 2014). Ward Thompson (2002) develops this last point by considering the apparent stigma of lingering without purpose within societies whose members feel they should be seen to be doing something. Could it ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Series page

- Title page

- Copyright

- Table of Contents

- Series Editors’ Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Chapter 1: A wager and a strategy

- Chapter 2: Taking an interest in the everyday lives of others

- Chapter 3: Forgetting the Outdoors: Inside the Office

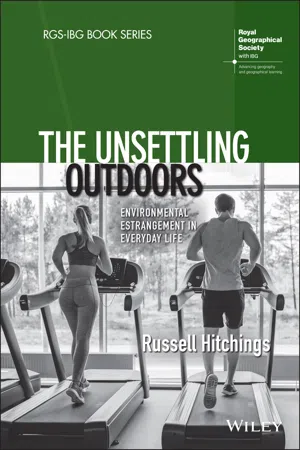

- Chapter 4: Avoiding the outdoors: on the treadmill

- Chapter 5: Succumbing to the outdoors: in the garden

- Chapter 6: Embracing the Outdoors: At the Festival

- Chapter 7: Conclusions

- Index

- End User License Agreement