![]()

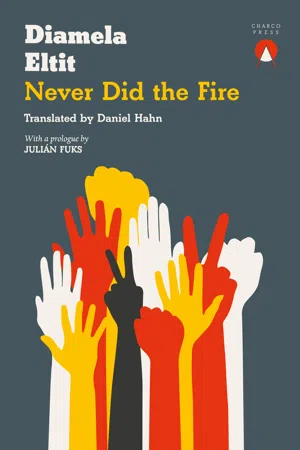

Diamela Eltit

NEVER DID THE FIRE

Translated by

Daniel Hahn

![]()

FOREWORD

by Julián Fuks

Can the subjugated speak? Can the oppressed speak? Can the disillusioned speak? Can the defeated speak? From out of the pages of this book, no exact answer to these questions will emerge. Within the pages of this book, the subjugated, the oppressed, the disillusioned, the defeated, all one voice, one single voice, speak. In the pages of this book, this subject, who is so often silenced, cannot but speak. Speak and, as far as possible, express the constant discomfort of the body, the meanness of successive days. To speak has become imperative. The final act of freedom in a world that wants them quiet, numbed, suppressed: finding words that will at last prevent them from not existing.

We are in an uncertain year, a year of dismay like so many others we have seen. In the year in question, one recollection recurs: the unpunished death of General Franco, the unseemly death of the fascist dictator untouched by any justice. Nothing to celebrate in that death, or in the insistent memory of the death: perhaps that’s the greatest expression of the defeat of so many emancipatory struggles, the absurd triumph of the Spanish dictatorship, or of almost all dictatorships. In this uncertain year, already distant from that occurrence that’s so real it becomes a symbol, there is no hope that might pay us a visit, no confidence that it could be possible to attain the slightest dignity, or at least an effective democracy.

We are once again shut up in a constrained space, inside a Beckettian room perhaps, the room from whose walls the same voice echoes incessantly. What’s different, however, is the delirium, what’s different is the madness that is ordered here – we are surrendered to the unending recollections of a life run through with politics. The experience of militancy becomes the centre of all memories, the many mistakes made during the resistance, mistakes that are re-enacted in the present, in the friction between bodies, in the non-viability of any real contact, of any understanding. Within the language, so intimate and so personal, of these bodies in conflict, the failure of direct action is made manifest, but another greater failure is made manifest too: the impossibility of reaching a more just, more human community, the evidence of a society condemned to perpetuate its violences. What’s different is the continent, what’s different is the time, is the historic trauma: we are in the very heart of the Latin American tragedy.

The voice that speaks to fill the silence, the voice that others want silenced, and it could not be otherwise, is the voice of a woman. The nameless narrator was unable to speak for decades – for centuries, for millennia, time here stretches out with no discernible limits – or at least she was unable to be heard, nobody wanted to hear her. No surprise that her tone now is burdened, at once, paradoxically, with pain and with indolence. This woman, too, is burdened, overburdened by a vast number of chores. Care for the man who oppressed her throughout her life, care for the child who is dying for all eternity, care for a whole multitude of decadent bodies. She only cannot care for herself and for her own body, her fragmented body, deprived of the integrity it once had. Her body has been stormed by all society, her cells no longer belong to her, nor does the sweat belong to her that seeps from her pores in this constant drudgery. Her own time does not belong to her – all she has left is her voice, the possibility of doggedly questioning the past and, with words, occupying the present.

Why talk, what use is it now, reckon up the losses or reconstruct the defeat, the successive and unmistakable defeat?, asks the man who shares the bed with her, and the man who is writing these words asks it too, deferring her pages with this dispensable prologue. This woman has no reason to explain herself, and nor does Diamela Eltit have any need to explain herself, having written this full-powered novel. In this woman’s voice, or in Diamela Eltit’s, literature is transformed into a visceral, intimate speech, a speech that comes from inside the body and never surpasses it and yet which touches us all relentlessly. A literature of intervening in bodies and in times, a literature for disturbing the order of silences. Let this woman speak at last.

Julián Fuks

São Paulo, November 2019

![]()

Never did the fire ever

play its part better as the dead cold

César Vallejo

![]()

For Rubí Carreño.

With thanks at the time of this book to

Silviana Barroso, Francisco Rivas

and Randolph Pope.

![]()

We are lying in the bed, surrendered to the legitimacy of a rest we deserve. We are, yes, lying in the night, sharing. I feel your body folded against my folded back. Perfect together. The curve is the shape that holds us best because we can harmonise and dissolve our differences. My stature and yours, the weight, the arrangement of bones, of mouths. The pillow supports our heads in balance, separates our breathings. I cough. I lift my head from the pillow and lean my elbow on the bed to cough more easily. It bothers you, my cough, and to some extent it worries you. Always. You move so as to let me know you’re there and that I’ve overdone it. But now you sleep while I maintain my ritual of wakefulness and drowning. I’m going to have to tell you, tomorrow, yes, it really will be tomorrow that I’ll need to cut back on your cigarettes, to ration them significantly or stop buying them altogether. We can’t afford them. You’ll clench your jaw and you’ll close your eyes when you hear me and you won’t answer me, I know it. You’ll remain unmoved as if my words were totally unfounded and as if the pack I faithfully buy you was still there, full.

You like it, you think it’s important, you need to smoke, I know this, but you can’t do it any more, I can’t, I don’t want to. Not any more. You’ll think, I know you will, about how you’ve kept yourself going on the cigarettes you systematically consume. That’s how it has been, but it is no longer necessary.

No.

No, I can’t sleep and in between the minutes, through the seconds that I cannot quantify, a worry inserts itself that is absurd but which declares itself decisive, the death, yes, the death of Franco. I can’t remember when it was that Franco died. When it was, what year, what month, in what circumstances, you told me: Franco’s died, he’s finally died lying there like a dog. But you were smoking and so was I at the time. You were smoking as you talked about the death and I was smoking and while all my attention was on your teenage face, openly resentful and lucid and also dazzling in its way, I stubbed out my cigarette knowing it was the last, that I wouldn’t smoke ever again, that I’d never really liked inhaling that smoke, and swallowing the burning of the paper. I feel your elbow resting against my rib, I think about how I still have my rib and I accept, yes, I surrender to your elbow and I resign myself to my rib.

I turn, put my hand on your hip and I shake you once, twice, fast, obvious. When did Franco die, I ask you, what year? What, you say, what? When did he die, I say, Franco, what year? In one movement you sit up in bed, quickly, filled with a muscular force you never exercise any more and which surprises me. You lean your head against the wall, but then immediately slip down between the sheets again to turn your back on me.

When, I ask you, when?

Your breathing agitated, you move towards the edge of the bed, I don’t know, you answer me, be quiet, woman, turn over, go to sleep. A precise day of a precise year but which is no part of any order. A scene that’s detached, inarticulate now, in which we were smoking, focused, so committed to that first cell of ours, while you, precociously wise, with all the fullness that talent can sometimes allow, you pronounced a few legitimate, coherent words that couldn’t be ignored and we all looked enraptured at you – your arguments – as you explained the death of Franco and I, transfixed by the toughness of your words, put out my cigarette possessed by a final disgust and watched the paper crushed against the filter, looked at it in the ashtray and thought, never again, that’s the last one, it’s over, I thought and I thought why had I smoked so much that year if I didn’t even like the smoke, not really. I can picture the ashtray, the stubbed-out cigarette with the scant strands of tobacco loose at its centre. I’ve got that. I’ve got Franco’s death too, but not the year, nor the month let alone the day. Tell me, tell me, I ask you. Don’t start, don’t keep on, go to sleep, you answer. But I can’t, I don’t know how to sleep without first retrieving the lost plot, without dodging the terrible blank in time that I need to draw to me. The cigarette butt crushed against the ashtray, my fingers, the sequence of your convincing words, lying there like a dog, in his bed, the killer or maybe you said: the murderer and my final disgust at the mouthful of smoke, the last one.

The public death of Franco, lying in bed, dying of everything, with practically no organs, you said, the tyrant, you were saying, dead of old or very old age, surrounded by his entourage, you were saying, by Francoists, doctors. At night, late, on the edge of an exhausting dawn, the discussions, the arguments continued, and among all the possible words, of course, yours were the ones that sounded most expert or most accurate, while I smoked right through that unwavering night until, all of a sudden, I felt truly acidic, in my lungs, and I had to put it out, the cigarette, for ever.

Then you offered me one, want a cigarette?, day was already breaking, no, I don’t. No, I said, I don’t want one, and I glimpsed in your eyes a flicker of concern mixed with an obvious disappointment. A first, nascent, unforgivable look of abandonment or of a material grudge. But tell me, when. Shut up. You shut me up at the exact moment the calamitous bedsheet became entangled, once again, in my legs and my arms, just sit up, move, while I arrange the sheet, furious, not understanding if my fury’s towards me or towards you, unconvinced. How could I have forgotten the year, a year you remem-

ber but won’t tell me, to prevent me from settling the matter of the cigarette.

Stalinist, Martín called me, later, many years on, at a time in which we no longer were (at this very moment Martín steps forward, he’s standing at the foot of our bed, out of place, denying my words, reiterating his lies in this century). He called me a Stalinist and you, listening to his words, hearing them, you turned your head, impassive as if he never had. Who was it called me a Stalinist, shut up. Who was it, I insist, shaking your hip. Oh, you say to me, I need to sleep, go on, sleep, please sleep, leave me in peace. You’ve raised your voice, you’re speaking to me in a tone that’s wild. Aggressive.

My eyes are burning from a dream that seems no more than a symptom. I can’t sleep, shut up. Stalinist, he skewered me with the word just like that, while I looked at you seeking your defence and you, already settled into indifference, remained apart, while I listened to words that spun madly without completely understanding the rage that was generating them. Stalinist, he called me. He repeated it. I do know who said it, Martín (from the edge of the bed he touches his head, he shows off, displays his outline that is visibly irregular, eroded). In my retina I hold his eyes and all the nuances of their expression, but now I’m waiting for you to be the one to say who it was, waiting to hear as much from your lips, from yours, why did you say nothing, what degree of desertion had you reached, quite unruffled, I remember it.

It doesn’t matter, you say to me, go to sleep, let it go, forget about it.

In the middle of an argument that seemed ridiculous, when everything had already become muddled, you had shown up just to listen ambiguously, marking your distance and your irony and I couldn’t, I wasn’t able to keep silent, I couldn’t manage it and I said, how come, and I said, seems unfair or inappropriate if you ask me, I managed to say both things or perhaps, perhaps I expressed, with a discomfort that had been soothed, I know it, that it was impossible to have a conversation in those terms and that was when the final condemnation was triggered, connected to a concise response: Stalinist. Move your leg, it’s bothering me, your trousers are scratching me, why do you have to sleep with your trousers on. Shut up.

But now dawn is going to break again. I know that afterwards we never mentioned what had happened, and we wielded a disproportionate politeness. We did it as we turned away from what was to be the final meeting of that cell. Yes. You behaved as though I deserved all deference, as if it were possible to believe that nothing had happened. But it was the final meeting of an intransigent year that none of the words you used could contain any longer.

You behaved like a dog.

You had already been transformed into a dog, I think now. I think this while my arm in its surrender to wakefulness tortures me with its unavoidable rubbing against the monolithic wall that surrounds us.

![]()

It was more than a hundred years ago that Franco died. The tyrant. Profoundly historical, Franco plundered, occupied, controlled. He was, of course, consistent with the part he had to play. One ...