CHAPTER 1 From Berenstadt to Boston

In his 1910 article “Judaism, Hebraism, Zionism,” Horace Kallen distinguished between three historical manifestations of Jewish ideals. Judaism was the rigid, ancestral faith he rejected. Hebraism, his guiding philosophy, represented organic, dynamic Jewish culture, which reflected the spirit of the Bible and Jewish history. Zionism was the pragmatic manifestation of Hebraism in the modern world. Although he did not personalize the essay, Kallen’s own ideological development mimicked this trajectory. This progression culminated in his theory of cultural pluralism.

Kallen’s formulation for the United States was a by-product of his reclaiming his Jewish heritage through Zionism. Understanding his Zionism requires an examination of his origins, along with the childhood ideologies he rejected and displaced. Kallen experienced cultural pluralism as an educational process of learning through encountering others. At the same time, in the spirit of philosophical pragmatism, Kallen formed cultural pluralism through his interactions with American diversity, in Boston and beyond.

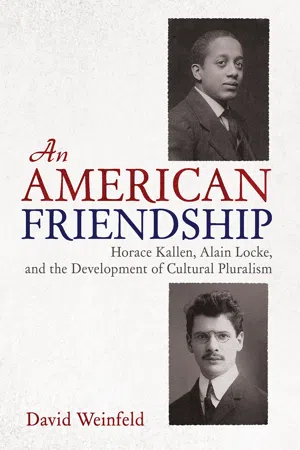

Kallen’s childhood encompassed his journey from Old World to New. The young Kallen encountered ideas, embraced them, fought with them, lived them. Years before he developed the term cultural pluralism in 1924, he had already enjoyed a multitude of experiences that he would use to fashion his ideas on diversity. Friendship, however, did not appear to be one of them. Kallen did not retain a single friend from primary school, high school, or college. His earliest memories were of his parents and teachers. He made some friends in the Harvard Menorah Society in 1906. He made his first non-Jewish friend in 1907, at the age of twenty-five. That friend was Alain LeRoy Locke.

Horace Kallen was born in Berenstadt, Germany (today Poland), in 1882, the first of eight children to an Orthodox rabbi and his wife. Five years later, the family immigrated to Boston’s North End, an immigrant neighborhood first populated by the Irish and later by Jews and Italians. Few Jews had settled in Boston before 1880, avoiding the conflict between older central European Jewish immigrants and newer eastern European ones that marked the New York Jewish experience. Many of Boston’s Jews came from Posen, a nominally German city more accurately described as Polish, giving Boston’s Jewish community a “Polish character.”1

The Kallens arrived with a massive wave of Jewish immigration. Boston’s Jewish population increased from five thousand to forty thousand between 1880 and 1900. Mostly Yiddish speakers from the Czarist Empire, the Kallens did not quite fit the mold. Horace’s father, Jacob, was a Yiddish speaker from Latvia but spoke German at home while serving as a rabbi in Germany, before he was expelled as a foreigner. He led a German-speaking congregation in Boston, Society Har Moriah. While Horace’s “long-suffering” mother worked tirelessly for “the liberation of the children,” his strict father hoped his eldest son would follow him into the rabbinate. He initially instructed Horace himself, but the local “truant officer” made the boy attend Eliot Grammar School.2

Horace Kallen bristled at the strictness of his Jewish education, both from his father and at cheder, the local Jewish school. As a teenager, he took steps toward independence. He hung out in Scollay Square, a “honky-tonk area” filled with “sports,” “saloons,” and “gay places.”3 To supplement the family finances, he read gas meters, sold the Boston Herald, blackened boots, clerked in a grocery store, assisted a potato peddler, and gave English, German, and French lessons.4

Linguistic proficiency was one of Kallen’s strengths. A native German speaker, he learned Hebrew from his father. After immigrating, he learned English and picked up Yiddish from his neighbors and schoolmates. At English High School, the oldest public school in the United States, he studied Greek, Latin, and French and developed an “excellent command of himself in various languages.” His language skills and “extraordinary mental powers” made him an “omnivorous reader,” such that his teacher James A. Beadly prophesied great success in college “departments of literature and philosophy.”5

Kallen came to Harvard highly recommended. In school he had developed an “excellent reputation” for being “honest, very ambitious, and industrious.” His teacher James E. Thomas, a Harvard alumnus, called Kallen “the possessor of a wonderful mind” who would “make a name for himself at Harvard.”6 Kallen graduated a year early, at seventeen, but took a postgraduate year to prepare for the Harvard curriculum.

Poverty defined Kallen’s childhood. In winter he frequently came to school without sufficiently warm clothing and developed a respiratory ailment that “hampered his work during the spring.” Nonetheless, his teachers remained confident in his talents. English and history teacher Albert Perry Walker praised his work ethic, “maturity of thought,” and “literary gifts, both critical judgment and of expression,” as “the most promising” he had ever seen.7

Kallen’s disposition earned him similar accolades. He appeared “uniformly kindly and courteous” to fellow students and teachers alike. Another teacher, William H. Sylvester called him “a young man of excellent moral character, and a scholar of first-rate ability.”8 He was a Franklin Medal Scholar, placing among the top “half dozen” in his class, including first in chemistry.9

Teachers attributed his success to his Jewish origins. Many knew he lived in “slim circumstances” and had to “work hard outside of school to keep the pot boiling.” He impressed chemistry teacher Rufus P. Williams as a “very promising fellow, unusually ambitious, and—like most of his nationality—not at all afraid of work.” Beyond the curriculum, Kallen attended “advanced” science lectures after school. As a senior, he “organized a group of small boys” to stay out of trouble, his first step in community activism.10

That same year, Kallen used his mother tongue to make an important discovery. He stumbled upon German translations of Baruch Spinoza’s Ethics and Theological-Political Treatise among his father’s books. Though Jacob Kallen observed Jewish law strictly, he fancied himself a scholar and kept these blasphemous works in the house. While Jacob approved of his son reading Spinoza, the heretic’s writings hastened Horace’s escape from traditional Judaism.

Still, some attachment to his father’s world remained. In 1899, Horace Kallen was “stage manager” for a standing-room-only concert put on by the Sons and Daughters of Zion, a Zionist group. Along with the music and dancing, amateur actors put on brief theater performances and “very clever impersonations.” Kallen played Macbeth. The following year, he spoke on Zionism to his father’s congregation, Society Har Moriah, at Minot Hall. Zionism was part of his life before he left for college.11

In the fall of 1900, eighteen-year-old Horace Meyer Kallen stood among the incoming freshmen at Harvard, the United States’ oldest college, ready to embrace modernity. Despite his teenage accomplishments, the Harvard freshman class may well have intimidated him. He did not recall “any kind of antisemitism” at Harvard under the relatively tolerant and philo-Semitic university president Charles William Eliot. Though being Jewish “was enough to cut one out,” Kallen did not remember his religion affecting his interactions with students or teachers in a negative way.12

Social class proved more significant. Kallen felt he “belonged to the other side of the tracks” and stood out as a poor Jew among wealthy white Protestants. He was a “ragged fellow” who worked his way through school, tutoring and taking odd jobs.13 He lived not in Harvard Yard with most other students but at a rooming house in Boston. Among his classmates in a European history course sat Franklin Delano Roosevelt, cousin of the vice president, who decades later would advance to the nation’s highest office. Though Kallen earned a B to FDR’s “gentleman’s” C, he undoubtedly felt less comfortable at Harvard than his well-to-do peer.

Jews did not figure prominently in Kallen’s undergraduate memories. He recalled “one or two Jews,” from Cleveland and Boston, but observed that “Jews were not visible at Harvard in my day.”14 He took two classes alongside Herbert Straus, scion of the wealthy German Jewish Macy’s department store fortune, but never mentioned him.15 Hastings Hall, one of the fanciest dormitories, with rooms “costing $350 per year,” was nicknamed Little Jerusalem and “suffered in reputation because a large number of Jews lived in it,” but Kallen likely spent little if any time there.16

Kallen attended classes with African American students but left no record of any thoughts about them. A relative rarity on campus, they were likely the first African Americans he encountered as peers. Whatever prejudices he brought toward Locke and other Black people later in life may have emerged from these experiences.

His college classmates had little impact on him. Kallen recalled, “The fellows you sat beside in the classroom were tangent, they sometimes borrowed your notes or they made some kind of comment in the course of a lecture, but that was all, that was that.”17 Kallen did not maintain any friendships from his undergraduate years, and the historical record does not reveal whether he had any.

Despite his limited social life, Kallen kept busy. He read meters for the Dorchester Gaslight Company and worked as a “salesman in a shoe store, and a shipper in a grocery.” In 1901 he “established a private school for boys, teaching elementary subjects.”18 All told he earned between seventy-five and one hundred dollars per year.

As a sophomore, Kallen moved to Civic Service House, a settlement house in Boston’s North End across from a fire station. Philip Davis, another Jewish immigrant, Harvard student, and volunteer at Civic Service House, compared the neighborhood to a “Russian fair, but a more cosmopolitan one.” He recalled constant commotion of “men, women and children in multicolored garb” navigating “pushcarts loaded with fruit and vegetables, fish and crabs, and edibles of every description that cluttered the streets and sidewalks.” As “cries of ‘hot tamales,’ ‘fresh bagels,’ and ‘Fish! Fresh Fish’ in Yiddish, Italian and Portuguese filled the air,” the pushcarts constantly scattered as fire wagons came and went. Kallen made his way through the hustle and bustle and up the stairs to the “unassuming” entrance of the house, a site far from the idyllic Harvard Yard but at once more familiar and educational.19

Religious antagonism from Catholics afflicted the poor Jews of Boston, which Kallen likely sensed. In 1902 sociologist and Boston settlement house leader Robert A. Woods noted that the Irish, in attempting to swing Italians to the Democratic Party, united over “their common enmity to the Jew.”20 Nonetheless, Kallen found a comfortable home for himself in returning to the immigrant life he had fled.

One of a dozen workers and volunteers, Kallen received a free room in exchange for services performed for the settlement. He taught American history and English and organized the “youth” of the house. He ran a club of “Italian anarchists” and another of “young Jews,” some older than him.21 Recalling his adolescence, he organized “the Bootblacks League” for kids who sold papers and shined shoes.22 He took boys “out to the country” to play football, visited them in their homes, ate meals with them, drank with them, and received a “great education,” more significant than anything he learned in the classroom.23

Kallen also learned from his fellow volunteers at Civic Service House, some of whom had similar immigrant backgrounds. House leader Meyer Bloomfield emigrated from Bucharest to New York. He graduated from City College and earned another undergraduate degree from Harvard.24 Philip Davis, born Feivel Chemerinsky in Motol, Russia (now Belarus), had also immigrated to New York, where he worked in a sweatshop. After struggling to organize workers there, Davis made his way to Chicago, where he met Jane Addams and volunteered at Hull House. He enrolled at the University of Chicago but transferred to Harvard in 1901. He eventually moved to Civic Service House, where he likely encountered Kallen. Davis probably told Kallen of his first cousin Chaim Weizmann, chemist and active Zionist, who would become Israel’s first president.25

Kallen’s experiences at Civic Se...