eBook - ePub

Commercial Horticulture - With Chapters on Vegetable Production and Commercial Fruit Growing

- 122 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Commercial Horticulture - With Chapters on Vegetable Production and Commercial Fruit Growing

About this book

This comprehensive guide to gardening for profit comprises six thorough and detailed sections by various experts on the subject. It is extensively illustrated with black and white drawings, forming a complete how to guide. Commercial Horticulture takes a comprehensive and informative look at the subject, and is a fascinating read for any gardener. Contents Include: Vegetable Production for the Markets; Commercial Fruit-growing; Commercial Glasshouse Work; Tomato and Cucumber Culture; Mushroom Growing; Commercial Bulb Growing. This book contains classic material dating back to the 1900s and before. The content has been carefully selected for its interest and relevance to a modern audience.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Commercial Horticulture - With Chapters on Vegetable Production and Commercial Fruit Growing by Various in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Agronomy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

XIII—COMMERCIAL HORTICULTURE

I. VEGETABLE PRODUCTION FOR THE MARKETS

CHAPTER I

Changes in Market Growing

At the beginning of the century vegetables were grown almost exclusively by market gardeners, and in consequence vegetable growing and market gardening were thought to mean the same thing. Now, market gardening is less simple, for the production of certain types of vegetables has been taken up by farmers, and market gardeners dare not attempt to produce these by their usual methods. Crops like Brussels sprouts, peas, &c., fitted in the farm rotation, and their cultivation could be managed with the normal farm machinery. In fact, whilst they were a little more difficult to grow than root crops, the vegetables could be marketed right away and a cash return secured. Such is the explanation offered for the rapid increases in the acreages of such crops as Brussels sprouts (124%), cauliflower and broccoli (70%), celery (46%), rhubarb (45%), peas (20%) and cabbage (18%). The figures in brackets give some measure of the increase of acreage to these crops made during the past ten years.

At the lower prices obtainable the crops mentioned above scarcely prove remunerative to grow on highly rented land by hand methods common to the market garden industry. They prove attractive, however, as a farm crop in a rotation, for costs are lower when horses and tractors do most of the work and home-made dung and fertilizers are used. The problem for the market gardener to decide is whether the farmers will continue to produce Brussels sprouts, celery, rhubarb, peas, &c., or whether these will be forsaken and the production of wheat, mangolds, swedes, &c., resumed. This aspect will have to be watched and studied and systems of production modified in consequence. The market gardener may cease to produce Brussels sprouts, peas, celery or cabbage, or perhaps he too will be able to “mechanize” his methods, and so remain a producer.

Machinery has come to stay in vegetable growing, and provided the area cultivated is large enough the costs of production can be lowered considerably. “Caterpillar tens” and other tractors are now used to secure deep and perfect cultivation that was once thought could only be secured by hand-digging. Machines are available that plant any Brassica plant—Brussels sprout, cabbage and cauliflower—giving each one a measured quantity of water and pressing the soil tightly round the plant. Special ploughs have been invented for moulding up the celery ridges and for lifting the matured crowns. With suitable ploughs and disc harrows even asparagus crops can be grown with but a fraction of the hand labour needed in the past.

For the Brassicœ, celery, carrots, parsnips and peas, machinery reduces costs, and in consequence the grower of these has to have a “mechanical sense” and fit his planting schemes to a standard pattern. Further information on “Machinery in Vegetable Production” is given by S. J. Wright in Scientific Horticulture, Vol. III, published by the Horticultural Education Association, S.E. Agricultural College, Wye, Kent.

TARIFFS ON VEGETABLES

Another big factor that will cause important changes in vegetable growing is the imposition of tariffs on imported vegetables. At first these were just luxury tariffs and imposed only on early vegetables; but when revised later on they were stabilized for certain vegetables over their whole period of home production. The tariffs now in force are of two types, or, rather, they bear unequally on the different kinds of vegetables. On onions, vegetables for pickling, Brussels sprouts, cabbage, celery and rhubarb, and many other vegetables the tax is but the 10% ad valorem tariff, whereas additional tariffs on a specific basis have been imposed on cauliflowers, salads, carrots, green peas, asparagus, green beans, tomatoes, cucumber and turnips.

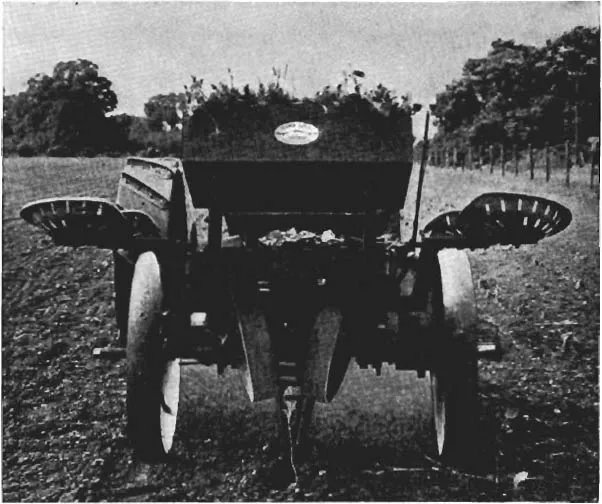

The Robot Automatic Planter which can plant seven Brassica plants per second. The machine opens up the ground, inserts the plant at the correct distance and depth, waters it and consolidates the soil around the roots.

A study of the statistical figures of imports will serve to demonstrate also that imports of these same vegetables (cauliflowers, salads, green peas, asparagus, &c.) are greater early in the season when attracted by good prices than later when prices have fallen.

The effect of these additional tariffs will be greatest in restricting early produce, and the least restrictive in the period of normal home production. From this it seems clear that the imposition of tariffs has not created conditions favourable for the wide expansion of the normal vegetable industry—a point that the farmer vegetable grower perhaps had not realized—though it has provided conditions for an expansion of an industry for the production of early vegetables. The imports of lettuce in March and April, and carrots and cauliflowers in May cannot be replaced with home produce except under a system of culture in frames. Early imported asparagus cannot be replaced by widening the area to asparagus in the open, but with crops hurried forward under glass, as is so much done in Italy.

With some few exceptions the statistics show that the present imports of vegetables for the main part comprise mainly the early produce from the sunny fields of Spain, N. Africa, Italy and France, or from the glasshouses and frames of Holland; and if these are to be replaced by home-raised produce it will mean a widening of the “glass” industry, especially that of frame culture. In Chapter III there are notes on specific crops, in which varieties suitable for frame culture and the methods of production are given special emphasis.

Artificial irrigation systems for watering the crops are almost inevitable for raising early crops by frame culture, and developments of these are expected.1

1 See “Irrigation for Market Garden Crops”, by F. A. Secrett, F.L.S., Journ. Royal Horticultural Society, July, 1935, pp. 294–303.

CHAPTER II

Vegetable Growing Under Glass

In this country glasshouse production has reached a high level seldom reached elsewhere, but the crops grown are limited to flowers, tomatoes, cucumbers, &c. Here and there lettuce and mint crops may be seen, though these would form the exception rather than the rule. Even the most recently erected glasshouses are cropped to tomatoes, for habit dictates this to be the orthodox crop to grow.

The houses could be used to supply early produce or other vegetables; but usually the proper methods of production are not well known and experimentation to find out might prove costly. Such crops as radish, lettuce, bunched carrots, early long turnips, May cauliflowers, early asparagus, vegetable marrows and sweet corn, will all give early crops in glass houses and their production should prove worth while if the supplies from the Mediterranean areas are to be restricted with tariff duties. It may, in fact, prove a blessing in disguise to give the house an occasional rest from tomatoes and to raise other crops instead.

CULTURE IN FRAMES

Actually tall houses are not needed to grow dwarf crops like radishes, lettuce or even cauliflowers, for frames are equally suitable and far less costly to build. This is a system of vegetable production that is little practised or understood in this country, though it had been widely exploited in both France and the Netherlands. Actually there are two systems—for the French use fermenting dung to form a hot bed, whilst the Dutch use a special frame and rely solely on the sun’s rays to supply the warmth. For the French or hot-bed system, quantities of stable dung are required annually, and this is the factor that limits its scale of development. The manure is built into a bed thick enough to provide heat, on the top of which is placed the black humus or terreau formed from the decaying dung of the previous year. Frames and lights are placed on this and production can begin at any time, for it is not very dependent on weather conditions. On these hot-beds early crops of lettuce, radish, turnips, carrots, cauliflowers and melons mature successively for the market with great rapidity, so that by early summer the season is over. The frames are packed away and the land cropped to lettuce or celery, or both.

Naturally these vegetables are young and tender and realize good prices in a market not over well supplied as yet with early produce; but the grower must secure good prices, for the system is costly of both capital and annual charges. The glass-lights and boards for the boxes may cost fully £1500 per acre. A pipe system to bring water to the frames has to be erected. Each year much dung has to be purchased. Throughout much labour is needed for all work done is by hand, and every light has to receive individual attention. The grower too must have knowledge of his job.

COLD FRAMES

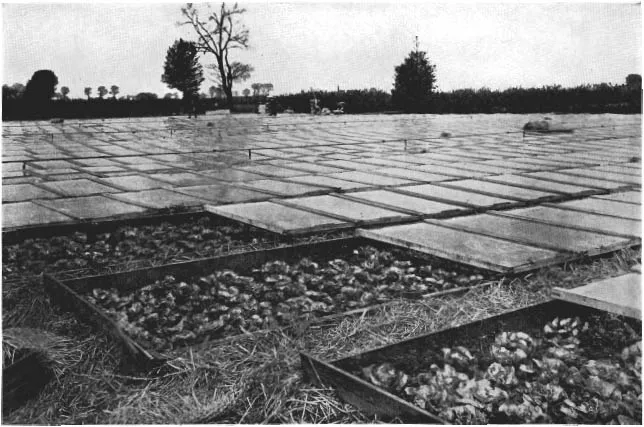

Though at first the Dutch growers copied the French, they have now developed a frame system of their own, and found out methods for the production of certain crops which are equally effective on the soils of the Netherlands. First we will give a description of the Dutch light, for that is a novel feature. Instead of many small panes of glass the Dutch use a single sheet (approximately 5 ft. by 3 ft.) and slide this into a grooved wooden frame, so that it in some way resembles a picture frame. The single pane of glass permits the maximum light intensity, and efficiently traps the sun’s rays, and at the same time there are no draughts and no water drip is possible. No putty is used, and usually no paint, so costs are lower, the usual price for the wooden frame and glass pane being 4s. to 4s. 6d. With these frames an acre could be covered for £800 to £1000. No hot-bed is used, for the frames are just placed in the soil, which should be light in texture, and well supplied with water from below. Some advantage is gained in building the soil into raised beds, for this provides better drainage, aeration and a warmer atmosphere. The soil used must be made very fertile with dung and artificials, and the top layer should be sifted to secure a very fine tilth. In fact, conditions are made to favour a natural rapid growth. The frames can be used in single rows—all sloping to the south; or they may be double frames with the lines running north and south. Actually the single frames are warmer and produce the earlier produce. In these frames and under cool conditions turnips and radishes are less successful; but excellent crops of lettuce, carrots and cauliflowers can be raised well in advance of the crops from the open land. Management is all-important, and the grower must know the exact varieties required, whether they need ventilation or not, and when water should be given or withheld. Further and more detailed information is given in Bulletin No. 65, “Frame Culture”, procurable from H.M. Stationery Office or any bookseller.

A field of lettuce in Dutch frames. The single panes of glass permit the maximum light intensity and obviate the “drip” nuisance

CHAPTER III

Growing and Marketing Vegetable Crops

A number of the canning factories need supplies of vegetables, but it is not wise to grow vegetables for this purpose unless contracts have been secured. The canners usually need special kinds—Lincoln peas, Keeney’s Green Refugee French beans, Plume celery and Detroit beetroot—that would not be very acceptable on the fresh market and so must go into the cannery or be wasted. This is recognized and accepted, and in consequence a system of “contract growing” has developed, under which the factories supply the seed, make a contract to take all the crop at a stated price, and give instructions concerning picking and the time of delivery. Well-grown produce only is suitable for the cans, and prices are not high, for market risks are small or negligible. The system has its appeal for many growers, but is specially convenient for those in the immediate vicinity of the canneries.

MARKETING

Vegetables seem a peculiar commodity out of which to construct an orderly market system, yet such is slowly being evolved. Cornish broccoli, for instance, that once was cut and hampered in any number and of all sizes, is now graded and packed in neat wooden crates. This method of grading and packing, so acceptable to the retail trade, is being taken up slowly in Kent and other places where broccoli and cauliflowers are grown, and will in time become the only method to gain market respect. The retail trades are becoming intolerant of the wicker basket and the net, and these will disappear. A start has been made in grading and packing a known quantity of cabbage, which is clearly a forward movement.

Lettuce, to secure a satisfactory sale, must be graded and packed two or three dozen in a crate to reach the customer in perfect condition.

Carrots, parsnips and celery are often sent as dug, dirty, and in bulk, loose in a truck, to the market just as they have been sent for many a year; yet the close observer can trace a new movement even with these, for here and there carrots and parsnips are washed, graded, and sent in assorted sizes to the market. There are several places too where celery is washed, the outside waste sticks removed, and the “edible” wrapped in cellophane paper sent to the market packed in neat boxes.

The large bundles of asparagus, too, are becoming less acceptable now that small bundles of gr...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- 1. Vegetable Production for the Markets

- 2. Commercial Fruit-Growing

- 3. Commercial Glasshouse Work

- 4. Tomato and Cucumber Culture

- 5. Mushroom Growing

- 6. Commercial Bulb Growing