![]()

* 1 *

Creating Religious America

MOST PEOPLE probably believe that Colonial America was far more religious than the nation is today—their impressions strongly shaped by pictures of Puritans dressed in somber clothing on their way to church. But most colonists were not Puritans; Puritans were not even a majority of those aboard the Mayflower. In 1776 the overwhelming majority of colonists in America did not even belong to a local church. Only about 17 percent did so, and even in New England only 22 percent belonged.1 As for the somber Puritans, they wore plain, drab clothing only on Sunday. On other days they tended to favor bright colors. Those who “could afford it wore crimson waistcoats and expensive cloaks,”2 and the women wore jewelry and very fancy clothing at appropriate times. Moreover, from 1761 through 1800, a third (33.7 percent) of all first births in New England occurred after less than nine months of marriage, so single women in Colonial New England were more likely to engage in premarital sex than to attend church.3

The very low level of religious participation that existed in the thirteen colonies merely reflected that the settlers brought with them the low level that prevailed in Europe. Then, as now, the monopoly state churches of Europe, fully supported by taxes and therefore having no need to arouse public support, were very poorly attended. This situation was not a new development. Contrary to another popular myth, medieval Europeans seldom went to church and were, at most, barely Christian.4 That state of affairs was not changed by the Reformation, which simply replaced poorly attended Catholic churches with poorly attended Protestant monopoly state churches.

In addition, some of the larger Colonial denominations, such as the Episcopalians and Lutherans, were overseas branches of state churches and not only displayed the lack of effort typical of such establishments but were also remarkable for sending disreputable clergy to minister to the colonies. As the celebrated Edwin S. Gaustad noted, there was constant grumbling by Episcopalian (Anglican) vestrymen “about clergy that left England to escape debts or wives or onerous duties, seeing [America] as a place of retirement or refuge.”5 The great Colonial evangelist George Whitefield noted in his journal that it would be better “that people had no minister than such as are generally sent over…who, for the most part, lead very bad examples.”6

In addition, most colonies suffered from having a legally established denomination, supported by taxes. The Episcopalians were the established church in New York, Virginia, Maryland, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia. The Congregationalists (Puritans) were established in New England. There was no established church in New Jersey or Pennsylvania, and not surprisingly these two colonies had higher membership rates than did any other colony.7

Therein lies a clue as to the rise of the amazing levels of American piety: competition creates energetic churches. As Adam Smith explained in 1776, established religions, being monopolies, inevitably are lax and lazy. In contrast, according to Smith, clergy who must depend upon their members for support usually exhibit far greater “zeal and industry” than those who are provided for by law. History is full of examples wherein a kept clergy “reposing themselves upon their benefices, had neglected to keep up the fervour of faith and devotion in the great body of the people; and having given themselves up to indolence, were become altogether incapable of making any vigorous defence even of their own establishment.” Smith went on to note that the clergy of monopoly churches often become “men of learning and elegance,” but they have “no other resource than to call upon the civil magistrate to persecute, destroy, or drive out their adversaries.”8 Smith’s claims were fully demonstrated by the weakness of European Christianity. But the lazy colonial monopolies did not survive in the United States, being replaced by a religious free market in which Smith’s analysis was fully confirmed.

PLURALISM AND PIETY

Following the Revolutionary War, state religious establishments were discontinued (although the Congregationalists held on as the established church of Massachusetts until 1833), and even in 1776 there was substantial pluralism building up everywhere. This increased rapidly with the appearance of many new Protestant sects—most of them of local origins. With all of these denominations placed on an equal footing, intense competition arose among the churches for member support, and the net result of their combined efforts was a dramatic increase in Americans’ religious participation. By 1850 a third of Americans belonged to a local congregation. By the start of the twentieth century, half of Americans belonged, and today about 70 percent are affiliated with a local church.9

From the early days, people generally knew that competitive pluralism accounted for the increasingly great differences in the piety of Americans and Europeans. The German nobleman Francis Grund, who arrived in Boston in 1827, noted that establishment makes the clergy “indolent and Lazy,” because

a person provided for cannot, by the rules of common sense, be supposed to work as hard as once who has to exert himself for a living.…Not only have Americans a greater number of clergymen than, in proportion to the population, can be found on the Continent or in England; but they have not one idler amongst them; all of them being obliged to exert themselves for the spiritual welfare of their respective congregations. The Americans, therefore, enjoy a three-fold advantage: they have more preachers; they have more active preachers, and they have cheaper preachers than can be found in any part of Europe.10

Another German, the militant atheist Karl T. Griesinger, complained in 1852 that the separation of church and state in America fueled religious efforts: “Clergymen in America [are] like other businessmen; they must meet competition and build up a trade.…Now it is clear…why attendance is more common here than anywhere else in the world.”11

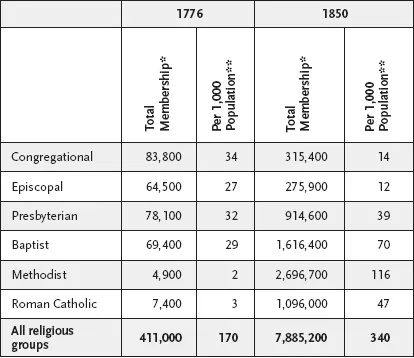

But competition did not benefit all of the American denominations, as can be seen in Table 1.1; some were unable (or unwilling) to compete. It would be very misleading to compute market shares in 1776 and 1850 as a percentage of church members since the rate of church membership precisely doubled during this period. This problem is eliminated by basing market shares on the entire population, churched and unchurched. That also takes into account the rapid growth of the population during this same period. When population growth is ignored, all denominations appear to have been quite successful; even the Congregationalists nearly trebled their numbers, and the Episcopalians more than did so. But when market shares are examined, it becomes obvious that the Congregationalists and Episcopalians had suffered catastrophic losses. The Presbyterians had held their own. The Baptists had made an immense gain (from 29 per 1,000 to 70), and the Methodists had achieved an incredible share of the religious marketplace, going from 2 per 1,000 to 116. During this era the Roman Catholics grew, too.

TABLE 1.1. CHURCH MEMBERSHIP, 1776–1850

* rounded to nearest 100

** rounded to nearest whole number

Source: Calculated from Finke and Stark 1992

PLURALISM MISCONCEIVED

Oddly, the recognition that competition among religious groups was the dynamic behind the ever-rising levels of American religious participation withered away in the twentieth century as social scientists began to reassert the charges long leveled against pluralism by monopoly religions: that disputes among religious groups undercut the credibility of all, hence religion is strongest where it enjoys an unchallenged monopoly. This view was formulated into elegant sociology by the prominent sociologist Peter Berger, who repeatedly argued that pluralism inevitably destroys the plausibility of all religions because only where a single faith prevails can there exist a “sacred canopy” that spreads a common outlook over an entire society, inspiring universal confidence and assent. As Berger explained, “the classical task of religion” is to construct “a common world within which all of social life receives ultimate meaning binding on everybody.”12 Thus, by ignoring the stunning evidence of American history, Berger and his many supporters concluded that religion was doomed by pluralism, and that to survive, therefore, modern societies would need to develop new, secular canopies.

But Berger was quite wrong, as even he eventually admitted very gracefully.13 It seems to be the case that people don’t need all-embracing sacred canopies, but are sufficiently served by “sacred umbrellas,” to use Christian Smith’s wonderful image.14 Smith explained that people don’t need to agree with all their neighbors in order to sustain their religious convictions, they only need a set of like-minded friends; pluralism does not challenge the credibility of religions because groups can be entirely committed to their faith despite the presence of others committed to another. Thus, in a study of Catholic charismatics, Mary Jo Neitz found their full awareness of religious choices “did not undermine their own beliefs. Rather they felt they had ‘tested’ the belief system and been convinced of its superiority.”15 And in her study of secular Jewish women who converted to Orthodoxy, Lynn Davidman stressed how the “pluralization and multiplicity of choices available in the contemporary United States can actually strengthen Jewish communities.”16 A national survey conducted in 1999 found that 40 percent of Americans have “shopped around” before selecting their present church, and these shoppers have a higher rate of attendance than do those who did not shop.17

THE POVERTY OF PERMISSIVE RELIGION

But if they have been forced to retreat from the charge that pluralism is incompatible with faith, critics of pluralism now advance spurious notions about the consequences of competition for religious authenticity. The new claim is that competition must force religious groups to become more permissive—that in an effort to attract supporters, churches will be forced to vie with one another to offer less demanding faiths, to ask for less in the way of member sacrifices and levels of commitment. Here, too, it was Peter Berger who made the point first, and most effectively. Competition among American faiths, he wrote, has placed all churches at the mercy of “consumer preference.”18 Consumers prefer “religious products that can be made consonant with secularized consciousness.…Religious contents…modified in a secularizing direction…may lead to a deliberate excision of all or nearly all ‘supernatural’ elements from the religious tradition…[or] it may just mean that the ‘supernatural’ elements are de-emphasized or pushed into the background, while the institution is ‘sold’ under the label of values congenial to secularized consciousness.”19 If so, then the successful churches will be those that minimize the need to accept miraculous, supernatural elements of faith, that impose few moral requirements, and which are content with minimal levels of participation and support. In this way, pluralism leads to the ruination of traditional religion. Thus did Oxford’s Bryan Wilson dismiss the vigor of American religion on grounds of “the generally accepted superficiality of much religion in American society,”20 smugly presuming that somehow greater depth was being achieved in the empty churches of Britain and the Continent. In similar fashion, John Burdick proposed that competition among religions reduces their offerings to “purely opportunistic efforts.”21 But it’s not so. The conclusion that competition among faiths will favor “cheap” religious organizations mistakes price for value. As is evident in most consumer markets, people do not usually rush to purchase the cheapest model or variety, but attempt to maximize by selecting the item that offers the most for their money—that offers the best value. In the case of religion, people do not flock to faiths that ask the least of them, but to those that credibly offer the most religious rewards for the sacrifices required to qualify.

FROM MAINLINE TO SIDELINE

Not so many years ago, a select set of American denominations was always referred to as the Protestant “mainline”: the Congregationalists, Episcopalians, Presbyterians, Methodists, American Baptists, Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), and, more recently, the Evangelical Lutherans. As the name “mainline” suggests, these denominations had such social cachet that when Americans rose to prominence they often shed their old religious affiliation and joined one of these bodies. Today, although media bias and ignorance often result in these groups still being identified as the mainline, that designation is very much out of date; the old mainline has rapidly faded to the religious periphery, a trend first noticed about forty years ago.

In 1972 Dean M. Kelley, a Methodist clergyman and an executive of the National Council of Churches, provoked a storm of criticism by pointing out a most unwelcome fact: “In the latter years of the 1960s something remarkable happened in the United States: for the first time in the nation’s history most of the major church groups stopped growing and began to shrink.”22 Kelley was being somewhat diplomatic when he referred to “most…major church groups,” knowing full well that the decline was limited to the mainline Protestant bodies.

Kelley’s book stirred up angry and bitter denials. Writing in the Christian Century, Carl Bangs23 accused him of using deceptive statistics, even though Kelley had relied entirely on the official statistics reported by each denomination. Everett L. Perry, research director of the Presbyterian Church, called Kelley an ideologue who “marshaled data…to support his point of view.”24 Martin E. Marty dismissed the declines as but a momentary reflection of the “cultural ...