![]()

PART I

SPIRITUALITY AND THE NURSING PROFESSION

Part I introduces the reader to the concept of spirituality and its relationship to nursing. In the first chapter, spirituality is defined as a universal human dimension that expresses itself through relationships, creativity, emotions, physical modalities, religion, and worldviews. Chapter 2 reviews the findings of research related to spirituality and religion and the implications of these findings for nurses.

![]()

1

SPIRITUALITY

DEFINING THE INDEFINABLE AND REVIEWING ITS PLACE IN NURSING

VERNA BENNER CARSON AND RUTH STOLL

I gave in and admitted that God was God.

—C. S. Lewis

In 1989, the first edition of this book was published with a focus on the importance of spirituality in nursing. At that time, because there was a paucity of research, publications, or even awareness regarding the importance of spiritual issues to health, this text was considered a seminal work. Other than texts from religious publishing houses, most health care literature had little to say about the topic of spirituality. This is not to say that there weren’t doctors, nurses, social workers, and physical, occupational, and speech therapists who recognized the importance of a patient’s spirituality and religious beliefs, but these practitioners may have been in the minority, and they weren’t publishing their thoughts.

Today, however, the landscape is very different for all health professionals. There is a wider acceptance that health care providers, in particular nurses, need to understand the spiritual and religious beliefs, needs, and practices of patients in order to provide whole person health care. Let’s take a look at a patient whose story underscores this importance.

Marcy was a married woman in her late twenties. She loved her husband dearly and counted among her blessings a close network of family and friends. Marcy had worked as a nurse and had always felt a call to her work. Now Marcy was in almost constant pain. She was confined to her home and spent most of her day in bed as a result of serious complications of systemic lupus erythematosus. Recently, she had undergone extensive surgery but was not healing well. During a home health visit, Marcy spoke to the nurse about her up-and-down physical condition, her fears that she would not get better, her physical symptoms of unrelenting headaches and pain, and the difficulty she had dressing her large wound. Over time, Marcy shared with the nurse that, despite her loneliness and her losses, she held tight to an unshakable hope and the courage to face whatever was ahead day by day. The nurse asked Marcy how she accounted for her strength and evident courage. Without hesitation, Marcy replied, “Prayer, the Bible, my husband, and friends.”

“What helps you pass the time?” asked the nurse. “What is meaningful and helps you feel worthwhile?”

Marcy confided that she had developed a new practice of “journaling.” She wrote letters of encouragement to others who were homebound due to illness; she prayed with people over the telephone. Even though Marcy was confined to her home, she reached out to the broader community. This hurting patient’s behavior expresses her particular spirituality. So what is spirituality?

The purpose of this chapter is to answer that question as well as to look at the relationship of spirituality to religion and worldview and how nursing approaches spirituality in clinical settings.

Spirituality Defined

Spirituality is an elusive word to define. Like the wind, we can see its effects but we can’t grasp it in our hands and hold onto it. We recognize when someone is in “low” or “high” spirits, but is that spirituality? We believe that a patient’s quality of life, health, and sense of wholeness are affected by spirituality, yet still we struggle to define it. Why? Most likely because spirituality represents “heart” not “head” knowledge, and “heart” knowledge is difficult to encapsulate in words.

Spirituality is described in a variety of ways: as a principle, an experience, a sense of God, the inner person. According to Mary Elizabeth O’Brien (2003, 4), “Spirituality, as a personal concept, is generally understood in terms of an individual’s attitudes and belief related to transcendence (God) or to the nonmaterial forces of life and of nature.” O’Brien concludes that most descriptions of spirituality include not only transcendence but also the connection of mind, body, and spirit, plus love, caring, and compassion and a relationship with the Divine (2003, 6).

Take a moment to ask yourself, “What does spirituality mean to me?” Ruth Stoll answered that question in the 1989 edition of this text. Her answer is still relevant. “It is who I am—unique, and personally connected to God. That relationship with God is expressed through my body, my thinking, my feelings, my judgments, and my creativity. My spirituality motivates me to choose meaningful relationships and pursuits. Through my spirituality I give and receive love; I respond to and appreciate God, other people, a sunset, a symphony, and spring. I am driven forward, sometimes because of pain, sometimes in spite of pain. Spirituality allows me to reflect on myself. I am a person because of my spirituality—motivated and enabled to value, to worship, and to communicate with the holy, the transcendent” (1989, 9). Dr. Stoll’s definition is clearly related to a belief in God. If you find that your definition differs significantly from Dr. Stoll’s, it may be because you are operating from a different worldview, a concept we will discuss later in the chapter. Dr. Stoll’s definition derives from a Christian theistic worldview.

Dr. George Fitchett (2002), a chaplain and researcher, defines spirituality as having seven distinct dimensions. The first dimension is that of belief and meaning, and refers not only to the individual’s beliefs, which give meaning and purpose to his life, but also to his personal story about how these beliefs are lived. The second dimension has to do with a sense of obligation to live out our professed beliefs. The third dimension deals with experiential and emotional aspects of spirituality. For instance, the experiences the individual has had in relation to the sacred, the Divine, or the demonic, and what emotional significance these experiences hold for her. The fourth dimension deals with our courage and willingness to grow spiritually, a process that entails putting aside existing beliefs and integrating new experiences. The fifth dimension relates to participation in formal and informal communities where members are able to share common beliefs, experiences, and meaning. The sixth dimension has to do with the source of authority for our beliefs. The seventh dimension focuses on where we turn for guidance when faced with painful life experiences. For instance, do we turn inward or outward to others? These seven dimensions are sometimes used to provide structure to spiritual assessments conducted by hospital chaplains (see chapter 8).

Chaplain Batchelor (2006, 8) describes spirituality as follows: “‘Breath,’ ‘wind,’ ‘meaning,’ ‘connected’—any or all of these terms may come to mind when one tries to grasp the concept ‘spirituality.’” For many, spirituality evokes reverence, peacefulness, and the very foundation for a meaningful life. It may do so either from within the framework of a particular religion or from an avowedly nonreligious perspective. For some who chafe from negative religious experiences, spirituality’s distinction from organized religion is what makes spirituality attractive. For yet others, this same distinction from organized religion may invite suspicion or outright rejection of spirituality as too individualistic or New Age. Batchelor’s definition covers a lot of ground and illustrates the two major ways that patients often view spirituality.

Many current definitions of spirituality tend to downplay any connections to God, but instead focus on humanistic concepts, individual feelings of well-being, and a sense of connectedness (Carson 1993, Smith and Denton 2005, Turner 1990). Plante and Sherman (2001) echo this observation in their remark that, for many, a spiritual quest for the transcendent may have nothing to do with the sacred. Increasingly, people are identifying any experience that makes them feel connected to something larger than themselves as being “spiritual.” Experiences such as being captivated by a beautiful sunset, playing on a sports team, or engaging in a political campaign have not traditionally been viewed as spiritual experiences. However, ordinary activities can be imbued with spiritual meaning if these activities are linked to the Divine, “as in the case of a Jew reciting a prayer while washing her hands or a Catholic who looks upon meal preparation as a sacrament” (Emmons & Crumpler 1999, 16).

Components of Spiritual Interrelatedness

According to Shelly and Miller (2006, 96), spirituality is all about relationships—“a relationship of the whole person to a personal God and to other people (or other spirits).” The core relationship is centered on the Creator, and the significance of this relationship reverberates and shapes all other relationships. The manner in which we connect with family, friends, our communities, our workplace, and even how we relate to ourselves—all are affected by our relationship to the Divine. Art, music, crafts, cooking, woodworking, volunteer activities, and sports can all be influenced by the way a person views God’s role in his life (Carson and Koenig 2004, 74; Emmons and Crumpler 1999). Even the act of finding meaning and purpose, an aspect of spirituality, is relational. When people struggle to make sense out of life and in that struggle they grapple with tough questions, such as, “Why me?” “Why now?” “What does it mean?” and “What difference do I make?” they are attempting to define the relationship of their lives to ultimate truth and reality. Nurses and other health care professionals not only witness patients and families as they grapple with these same questions; nurses grapple with the same questions thesmelves as they face the limits of their skills and abilities to make people better, to ease pain, and to create a healing environment (Carson & Koenig 2004, 74).

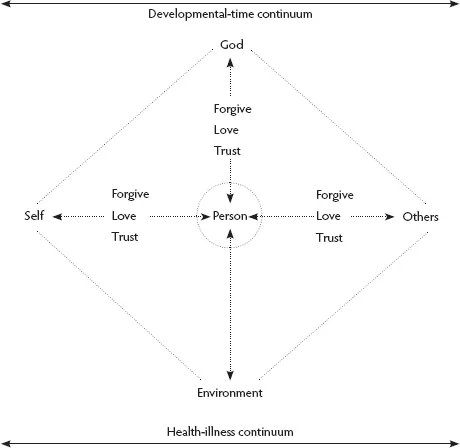

The integral nature of relationship to spirituality suggests both a vertical and a horizontal dimension. The vertical dimension has to do with the person’s transcendent (beyond and/or outside self) relationship, the possibility of a personal relationship with a Higher Being—God—not necessarily as defined by a particular religion. The horizontal facet reflects and “fleshes out” the many ways in which a personal relationship with the Divine influences our beliefs, values, lifestyle, quality of life, and interactions with ourself, with others, and with nature. As we will see later on, a person’s perception of and experience with the Transcendent will in great measure influence how that person views life and copes with crises of illness, suffering, and loss. Figure 1–1 depicts the two-dimensional nature of spirituality in a visual model.

Looking at the box, you can see that there is a continuous interrelationship between and among the inner being of the person, the person’s vertical relationship with the transcendent or whatever supreme values guide his life, and his horizontal relationships with himself, others, and the environment. These relationships are depicted by the inner dotted lines in Figure 1–1. The person’s relationships are grounded in expressions of love, forgiveness, and trust, and result in meaning and purpose in life. Noted above and below the model depicting the inner person are factors that continuously influence the spiritual well-being or distress of the person (see Part IV).

Figure 1–1 Spiritual interrelatedness, or integration, comes about through forgiveness, love, and trust, resulting in meaning and purpose and hope in life. (Redrawn by permission of Ruth I. Stoll. © Ruth I. Stoll, 1987.)

Spirituality: Whole Person Perspective

A person’s human spirit does not reside in a vacuum; rather, it is housed in a physical body. In other words, we are embodied spirits. The person is a whole being who is more than and different from the sum of her parts and cannot be separated into segments for diagnosis and care. The body, mind, and spirit are dynamically woven together, one part affecting and being affected by the other parts. Figure 1–2 depicts an adaptation of a model, developed by Stallwood and Stoll (1975), which serves to illustrate a person’s wholeness.

The following descriptions are meant to clarify the meaning of each circle in the model and the interrelatedness of the identified parts. The outer circle represents the physical body—what is seen and experienced by others. Our bodies allow us to be in touch with the world through our senses; our abilities to touch, taste, hear, see, and smell. The second circle represents the psychosocial—the dimension that ...