eBook - ePub

The Connections Paradigm

Ancient Jewish Wisdom for Modern Mental Health

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This book introduces an approach to mental health that dates back 3,000 years to an ancient body of Jewish spiritual wisdom. Known as the Connections Paradigm, the millennia-old method has been empirically shown to alleviate symptoms of stress, anxiety, and depression. After being passed down from generation to generation and tested in clinical settings with private clients, it is presented to a broad audience for the first time.

The idea behind the paradigm is that at any given moment, human beings are either "connected" or "disconnected" across three key relationships. To be "connected" means to be in a loving, harmonious, and fulfilling relationship; to be "disconnected" means, of course, the opposite. The three relationships are those between our souls and our bodies, ourselves and others, and ourselves and God.

These relationships are hierarchal; each depends on the one that precedes it. This means that we can only connect with God to the extent that we associate with others, and we cannot connect with others if we don't connect with ourselves. The author, Dr. David H. Rosmarin, devotes a section to each relationship and describes techniques and practices to become a more connected individual. He also brings in compelling stories from his clinical practice to show the process in action.

Whether you're a clinician working with clients, or a person seeking the healing balm of wisdom; whether you're a member of the Jewish faith, or a person open to new spiritual perspectives, you will find this book sensible, practical, and timely because, for all of us, connection leads to mental health.

The idea behind the paradigm is that at any given moment, human beings are either "connected" or "disconnected" across three key relationships. To be "connected" means to be in a loving, harmonious, and fulfilling relationship; to be "disconnected" means, of course, the opposite. The three relationships are those between our souls and our bodies, ourselves and others, and ourselves and God.

These relationships are hierarchal; each depends on the one that precedes it. This means that we can only connect with God to the extent that we associate with others, and we cannot connect with others if we don't connect with ourselves. The author, Dr. David H. Rosmarin, devotes a section to each relationship and describes techniques and practices to become a more connected individual. He also brings in compelling stories from his clinical practice to show the process in action.

Whether you're a clinician working with clients, or a person seeking the healing balm of wisdom; whether you're a member of the Jewish faith, or a person open to new spiritual perspectives, you will find this book sensible, practical, and timely because, for all of us, connection leads to mental health.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Connections Paradigm by David H. Rosmarin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychologie & Psychologie clinique. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

Introduction to Inner Connection: Body and Soul

Inner Connection involves connection between the body and the soul. Of the three domains of connection, Inner Connection is the most fundamental, yet it is the most abstract and thus the most difficult to describe. Interpersonal dynamics are readily observable as they occur among tangible bodies in real space, and even those who do not engage in prayer or other acts of spiritual reflection usually have some sense of what it means to relate to God or an infinite spiritual existence. But Inner Connection is vastly harder to grasp because it occurs in the mysterious inner realm where souls and bodies meet. While this enigmatic setting blurs the line between two distinct elements and leads many of us to perceive ourselves as unified, monolithic entities, according to the Connections Paradigm, we are actually made up of two complementary and distinct parts.

Rabbi Moshe Chaim Luzzato, the great eighteenth-century Kabbalist, wrote that the division of each person into a body and soul should not be regarded as an abstract metaphor but as a literal description of the human condition. A human being is made up of two discrete elements. Reflecting this conception, the common Hebrew greeting Shalom Aleichem, which literally means “peace unto you,” is phrased in the plural even when it is used to address an individual. In fact, there is a common custom among scholars of Jewish mysticism to greet individuals with the double saying “Shalom, Shalom,” which is an explicit double greeting of peace unto the two entities of the body and the soul. Notably, Judaism is hardly the only faith or philosophical system to recognize human duality. Various interpretations of body-soul dualism, or a similar concept termed “body-mind dualism,” have been discussed by Christian theologians, Platonic philosophers, and perhaps most famously by the French Dutch philosopher Rene Descartes.

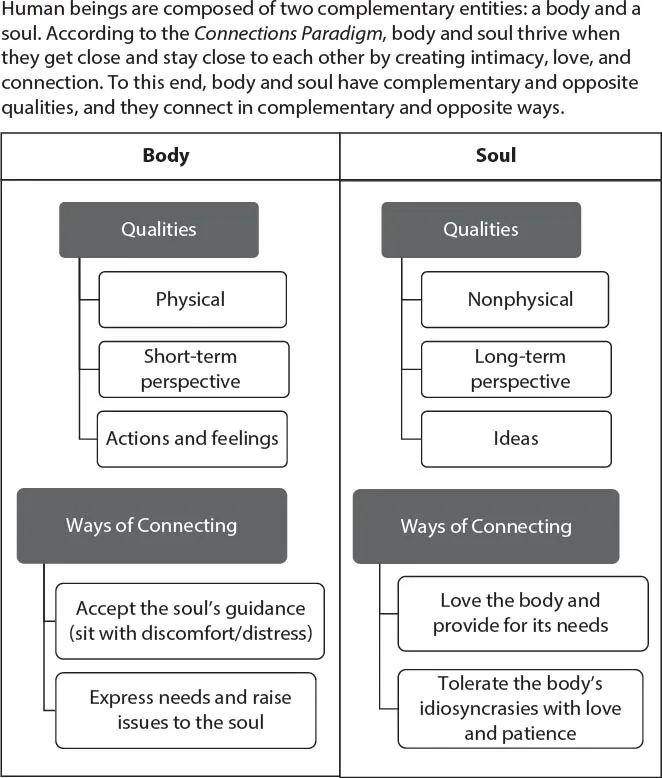

The distinction between body and soul becomes clearer when we consider the significant differences between them (figure 2). The body is composed of physical matter, which can be directly observed by the senses, and it is motivated by wants and needs that pertain to its ability to thrive in the physical world. It needs food, sleep, mental stimulation, physical activity, various kinds of social engagement, and sexuality. The body’s needs are simple, but they can quickly become critical when they are not met, so it seeks to satisfy them to the greatest extent possible in the shortest amount of time. It is disinclined to forgo its needs for any amount of time even if doing so temporarily will guarantee its long-term security. It is impressed by size and numbers, and it has little regard for beauty. It cares for other people only to the extent that they can satisfy its needs.

The soul is a vastly different creature. It is nonphysical, existing in a realm beyond conscious perception, and interacting with physical reality only through its worldly counterpart, the body. Love is its highest ideal, so when it comes to connection with God and other people, it is much more eager than the body. It has little regard for the physical pleasures that the body enjoys, and even finds them repulsive, but it can learn to appreciate the body’s physical beauty and the elegant simplicity of its needs. It focuses on long-term achievements that carry spiritual meaning such as closeness with God and other souls. Its goals can rarely be met in a short period of time, but lacking any physical needs, it is perfectly suited to forgo gratification for as long as it takes. It is even willing to sacrifice its body’s own needs, sometimes even its body’s life, for the sake of another person or a higher cause. One can easily imagine why the body and the soul do not make the easiest partners.

FIGURE 2 Contrasting the Body and Soul

Perhaps the most significant difference between the body and soul, however, is that they speak mutually unintelligible languages until they each develop the requisite sensibilities to understand each other. Due to its lofty spiritual perspective and noncorporeality, the soul speaks an abstract language of ideas, whereas the physical body speaks the language of actions and feelings. The soul’s ideas can engage the body and become part of its own goals only after they are distilled into clear, unambiguous behavioral guidelines that the body understands to be both beneficial and achievable. Furthermore, the soul’s intellectual approach needs to penetrate the heart in order to truly impact the body.

Although the soul and body have many differences, they have several significant similarities. Though spirituality is primarily the soul’s domain, the body also benefits from prayer and spiritual reflection because, when it understands its role in the soul’s higher goals, it can come to value itself as an important component of a greater meaning. Conversely, the soul has no physical needs, but it derives satisfaction from the physical activities that allow it to cultivate beauty and connection. Most important, the body and soul share one essential purpose: to get close and stay close to each other in a symbiotic and mutually beneficial relationship.

Whether or not we realize it, much of our daily lives involves navigating the divergent wants and needs of the body and soul. Perhaps we can understand this better when observing children. Kids are especially prone to disconnection because connection requires time, sustained effort, and wisdom, and kids are typically impatient and improvident. For instance, as we will discuss further in later chapters, a connected soul helps its body adhere to a diet that facilitates health, productivity, and clarity of thought. But kids usually prefer to eat whatever is tastiest when they are hungry, because without guidance from their souls, their bodies choose to freely eat whatever is most appealing. Children also have little regard for time and like to do what is most enjoyable at any given moment. While adults strive to develop stable, achievable career goals, the noncommittal soul of a young boy may want to be a firefighter on one day, a truck driver on the next, then an astronaut, and so on. Such imaginal play is of course an important part of childhood development, but it reflects the turbulent relationship of the child’s soul with its material counterpart, its fickle body. The child’s body is motivated to do what it views in the moment as important, and it does not work together with its soul in a connected relationship to achieve its goals. Consequently, most children have little hope of achieving high levels of connection until they mature. And unfortunately, the tendencies toward disconnection that characterize childhood often persist into adolescence and even adulthood, causing spiritual unfulfillment and emotional distress for years or even decades.

I first discovered the universal significance of body-soul conflict in psychological distress during my PhD studies. I was working as a therapist in training at a state-funded clinic in Bowling Green, Ohio, and studying the Connections Paradigm with Rabbi Kelemen over the phone whenever I had the time to do so. The clinic primarily served underprivileged communities, and many of my patients were seeking clinical professional help for the first time after enduring unremitting hardship and emotional struggles for many years. One patient was a survivor of childhood sexual assault who started coming to the clinic in his early twenties. He was struggling with drug abuse and had recently tried to take his own life. After his suicide attempt, he continued to struggle with severe depression, but he promised himself and his family that he would live and stay off drugs no matter how difficult his life continued to be. Quite literally, his body was running amok, and I had the honor of helping his body recognize the benefits of heeding his soul’s guidance. There was also a woman who had such intense post-traumatic stress disorder from growing up during the Nicaraguan Contra War that she woke up screaming from nightmares almost every night. She had three teenage children at home and worked fifty hours a week to support them while pursuing a nursing degree online, all the while contending with debilitating flashbacks and exhaustion and depression due to insomnia. In her case, her soul was pushing her body to the brink, and I had to encourage taking a much softer and gentler approach of relating to herself. I had another patient who had fallen into alcoholism after being paralyzed from the waist down in a work accident. He was severely depressed because he could not imagine any worthwhile future, and he could not imagine getting through a single day without liquor to numb his physical and emotional pain. For him, the problem was twofold: his soul had not validated his body’s loss or provided appropriate guidance in the wake of the accident, and his body was turning away as a result.

To be clear, all of these and many other patients presented with clear clinical diagnoses that generally gradually responded well to secular treatments that I was learning in college, and it was deeply satisfying to help them improve. In many cases, I found that secular approaches facilitated the body-soul connection, albeit without explicitly referring to the body or the soul. But in many other cases, individuals were not presenting with clinical diagnoses, and the treatments I was taught to provide were not effective. Some individuals came for help with mild anxiety or depression, but truthfully they were seeking help in sorting out, or simply discussing, which direction to take in life. These were hardworking people with immense responsibilities that they were, for the most part, handling with unbelievable finesse. They did not come to treatment to cure some crippling disorder, but rather with the hope of gaining a higher perspective on how to make life decisions. In past generations, they might have sought the guidance of their parents or even clergy instead of psychological treatment, but many of them did not have close relationships with their families or religious leaders. Furthermore, within their social circles, they wanted to appear fully competent and content, and the therapy room offered a safe place where they could confide in someone outside their social sphere that they were feeling lost in life. This was initially a difficult role for me to fill. I had spent my postsecondary education in classrooms studying diagnostic models and evidence-based approaches to treatment, with excellent professors who had taught me how to treat severe psychological distress; but in all my training I was never taught how to make greater meaning of life circumstances or provide guidance for life direction. More centrally, many of my patients simply wanted to be inspired and were seeking my advice, and all I could offer them was a sympathetic ear, which, to me, felt pathetically insufficient.

Between classes, clinical research, and therapy sessions, graduate school was perhaps the busiest time in my life, but I made time to study the Connections Paradigm with Rabbi Kelemen by phone. During one of our discussions he noticed that I was preoccupied, and he asked me what was on my mind. “Some of my patients are making progress,” I said, “but others are seeking life direction and, to be honest, that is outside my skill set as a psychologist. My clinical supervisors keep telling me to stay the course, but I really feel like something is missing from the approach I’m being taught to use.” Rabbi Kelemen is a well-rounded thinker with a general understanding of clinical psychology. We had long discussed the potential of spiritually oriented treatments to improve patient care, but I was still in the early stages of learning how to incorporate religiosity into clinical practice. He suggested that the patients I was struggling to help could benefit from spiritually oriented therapy, and specifically the Connection Paradigm. “So your patients don’t have full-blown mental health disorders,” he said, “yet they are clearly struggling. Some are looking for meaning or direction. That only happens when one’s body and soul aren’t getting along. Sometimes the soul struggles against the body’s limitations, and other times the body doesn’t accept the sage counsel of the soul.” I knew that my mentor was referring to the Connections Paradigm, and I decided to take his advice seriously. After we spoke, I thumbed through my session notes and began to conceptualize them in terms of Inner Connection, trying to identify the body-soul conflicts that were contributing to my patients’ distresses. Things were starting to come together.

In my second year of graduate school, I met Sharon, one of the most memorable and significant patients of my career. She was an undergraduate at Bowling Green University and was considering a career in social work, but was plagued by self-doubt and disorganization. At the beginning of our first session, I asked Sharon, as I always ask new patients, why she was seeking help. Being somewhat familiar with clinical terminology, she told me flatly, “I am not interested in being diagnosed.” She said that she had had a bad experience with a psychiatrist during high school who misdiagnosed her with depression within five minutes of their first session and sent her home with a prescription. “I was never depressed, and the antidepressant didn’t help me. In fact, I felt worse after I started taking them. And by the way, that session was only thirty minutes and he gave me prescription slips for a three-months’ supply. At our next session, which was just fifteen minutes, I told him the meds didn’t work so he just upped my dose, handed me some slips, and sent me home. I kept taking them for a while because my mom wanted me to. She said he was a doctor so I should trust him. But they never worked, and the whole thing was a complete waste of time. So, I don’t want you to tell me I’m depressed or anxious or whatever. The truth is that I don’t even meet clinical criteria for anything. I am just feeling lost and don’t know what to do.”

“I see,” I responded. “Do you know why I chose you?” she asked.

“I beg your pardon?” I asked.

“The office let me choose, and there are six other therapists here. I chose you because I knew you were a rabbi,” she responded.

“I’m not a rabbi,” I said.

“Oh, well I knew at least that you are religious. I saw you wearing a yarmulke in your picture. I respect Judaism,” Sharon said, and added, “I’m religious too, Catholic. It’s very important to me, and I don’t think anyone could understand my problems if they don’t believe in God. It’s a shame that so many psychologists and social workers are atheists nowadays. I blame Freud.”

This conversation was my perfect opportunity to begin discussing the Connections Paradigm with Sharon. She listened enthusiastically as I explained the core concept of connection in general, and body-soul connection in particular. Her eyes welled up with tears of happiness during this session, and she smiled broadly. Her only comment was as follows: “It’s a tragedy that most therapists don’t bring up spirituality. My goal is to make the world better. I don’t want money and I know I won’t be happy until I find my calling. Right now, I am leaning towards becoming a social worker, but I can’t make up my mind. I have a lot of baggage and bad habits that are holding me back. A spiritual approach is exactly what I need.”

Over the next few sessions, Sharon shared that she had a difficult childhood in Youngstown, Ohio. Her father left the family when she was six, and shortly afterward her mother turned to alcohol. The family struggled to make ends meet. “I have a younger sister and brother, 13 and 16, and they’re still at home. My mom is in no condition to take care of them; she can’t even take care of herself. I love her and she did a lot that I’m grateful for. She took me to church and she never hit me or even yelled at me. She’s very loving. But she gave me some bad habits too.” Sharon shared that she started drinking in high school to cope with stress. While her drinking never got out of control as it did for her mother, it did have consequences. One night during her junior year, Sharon was so inebriated she ended up in a one-night stand with a total stranger. A few weeks later she realized she was pregnant, and she terminated the pregnancy without telling anyone. “Even at the time I was so conflicted, but I felt like I had no other option,” she told me. “I didn’t even tell my mom, and she still doesn’t know. I had my whole future ahead of me and my mom always prayed that I would get out of poverty. But to this day, I don’t know if I did the right thing. I’m not sure I’ll ever get over it. That was when I went to the psychiatrist,” she told me. “My mom saw I was struggling and sent me to my doctor, who made the referral. But obviously, pills were not going to alleviate my inner struggle.”

In our sessions, I encouraged Sharon to facilitate conversations between her body and soul: for her body and soul to speak with each other on a regular basis. Sharon’s body was encouraged to tell her soul her regrets, fears, hopes, preferences, wants, desires, and anything else on her mind. Her soul was encouraged to patiently listen, validate her feelings, and provide guidance when a clear path was evident. Sharon was encouraged to have these conversations daily for just two or three minutes.

“So, you want me to speak to myself?” Sharon asked when I introduced this idea.

“Not exactly. Remember that according to the Connections Paradigm your body and soul are separate entities. I’m encouraging them to speak with each other,” I replied. “Part of the goal is for you to recognize each and every day that you have a soul to go to for help, and also that you have real material and emotional needs. That duality is something all human beings need to recognize about themselves.”

“Am I supposed to do this in public? People are going to think that I’m crazy,” Sharon said with a smile.

“That’s a good point. . . . It’s fine to have body-soul conversations when your body and soul are alone with each other,” I responded.

“Ok. What should we speak about? And how long should these conversations be? This is a nice idea, but practically speaking what should it...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Introduction

- CHAPTER 1: Introduction to Inner Connection: Body and Soul

- CHAPTER 2: Inner Connection Part I: Accepting the Soul’s Guidance

- CHAPTER 3: Inner Connection Part II: Loving the Body and Providing for Its Needs

- CHAPTER 4: Inner Connection Part III: Expressing Needs and Raising Issues to the Soul

- CHAPTER 5: Inner Connection Part IV: Tolerating the Body’s Idiosyncrasies with Love and Patience

- CHAPTER 6: Introduction to Interpersonal Connection

- CHAPTER 7: Interpersonal Connection Part I: Three Levels of Noticing the Needs of Others

- CHAPTER 8: Interpersonal Connection Part II: Providing for the Needs of Others

- CHAPTER 9: Interpersonal Connection Part III: Noticing Our Disconnection from Others

- CHAPTER 10: Interpersonal Connection Part IV: Remaining Connected to Others

- CHAPTER 11: Introduction to Spiritual Connection

- CHAPTER 12: Spiritual Connection Part I: Recognizing Our Limited Scope of Control

- CHAPTER 13: Spiritual Connection Part II: Recognizing God’s Order and Design in the World

- CHAPTER 14: Spiritual Connection Part III: Developing a Godly Vision

- CHAPTER 15: Spiritual Connection Part IV: Exerting Heroic Efforts for God

- Conclusion

- Acknowledgments