- 188 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Collotype And Photo-Lithography

About this book

Many of the earliest books, particularly those dating back to the 1900s and before, are now extremely scarce and increasingly expensive. We are republishing these classic works in affordable, high quality, modern editions, using the original text and artwork.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Collotype And Photo-Lithography by Julius Schnauss in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & History of Photography. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER IV.

_____

COLLOTYPE.—APPARATUS.

BEFORE commencing any practical work it will, of course, be necessary to procure various utensils and material not usually found in the photographic studio. All these should be procured from reliable dealers and of the best quality, for the evil consequences of false economy will make themselves felt in endless failures. The best to be obtained are none too good for collotype. In the practice of photography the whole success depends on a series of apparent trifles, and the same may be said to hold good, but in a far greater degree, in this process, which is one in which the difficulties can scarcely be overestimated.

The photographer will most likely be already in possession of many pieces of apparatus he may utilise—for instance, dishes. The best and dearest are those of china; but for many—in fact, most—collotype purposes, those of tin or zinc may be used.

For warming or cooking the gelatine solutions tin vessels are the handiest, as they easily conduct the heat and are unbreakable. Although the chromated gelatine may remain in them for a short period without harm, it is not advisable to allow it to do so for any length of time, but to remove the solution and wash the vessel thoroughly with hot water, and at once carefully dry, otherwise they will soon corrode, and contaminate the gelatine solutions. The best utensils to use are wide-mouthed shallow jugs, as they are easily kept clean, and in them the chromated gelatine solution keeps well, and with their use no fear of decomposition need be entertained.

Filtering the gelatine solutions is a somewhat troublesome matter, and should be effected at a high temperature and as quickly as possible. The simplest method is to procure a piece of perfectly clean flannel of suitable size, thoroughly moisten it, and insert into a brass ring, which is provided on the outside with small barbel hooks, to which the flannel is fixed, as in the retinaculum of the chemist. The ring is provided with a clip and handle, by the former of which it may be attached to a vessel of almost any size, and the latter is a convenience in holding it over plates to which the gelatine has to be applied. A careful filtering is obviously essential to the production of clean plates. Many complicated filtering appliances have been devised for gelatine and other solutions difficult of filtration, as, for instance, those of albumen or gum. Baron Szretter describes in the “Photographische Correspondenz,” 1878, an apparatus constructed by him. It consists of two vessels, an upper and a lower one, which by means of longer or shorter tubes communicate with each other in accordance to the stronger or weaker pressure required by the liquid to be filtered. Soldered round the upper rim of the lower vessel is a ring of sheet brass, about two to three in cm. width; over this ring the filter paper is placed, which again is covered with a piece of strong felt enveloped in flannel. To prevent the liquid escaping round the sides of the ring a strong iron ring is applied, which by means of a screw presses against the felt so that no space exists between the ring and the paper. To prevent the pressure of the liquid forcing the felt out of position, and so tearing the paper, a metal wire gauge is used to keep the felt in place. The liquid placed in the upper vessel passes through the tube into the lower vessel through the paper and felt layer. When it is necessary to warm the solution to be filtered, as in the case of gelatine, the whole apparatus is covered with an outer covering, and on the other side a pipe is applied for the purpose of effecting a circulation of the heated liquid, which is thus kept constantly rising through the one pipe and returning through the other.*

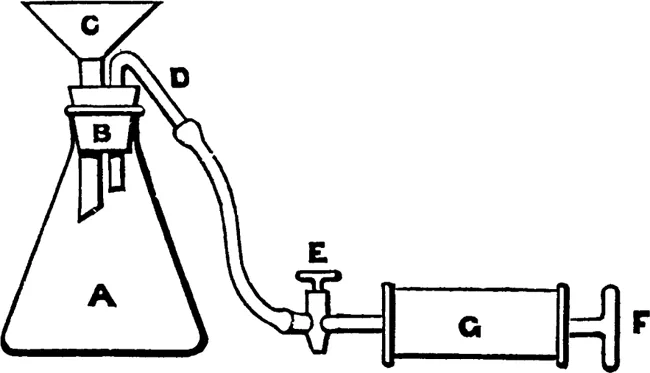

Fig. 1.

Heat is sustained at an even temperature during the whole operation by means of a small lamp. A simple method of filtering such solutions is to pass them through purified sheep’s wool, or spun glass, a quantity of which is placed in the tube of the funnel. The whole apparatus may be placed in a warm oven during the process, or the drying box may be utilised for the purpose.

Printing Frames of different sizes will be found to hand in the photographic studio, and may be utilised without alteration for printing the collotype plates, if they are deep and strong enough to bear the necessary pressure, which is usually applied through the medium of springs; these are better removed, and wooden wedges inserted in their stead between the cross-bars and the loose wooden back of the frames, as by these means far more pressure may be applied. By lifting the one half of the hinged back of the printing frame an examination by transmitted light of the collotype plate may be made and an experienced operator will in this manner judge the exposure of the plate.

The Actinometer is, however, recommended, particularly for a beginner, as it greatly aids in forming a correct idea of the exposure.

The Drying Box is of great importance to the successful working of the process. The opinions of the various practitioners with regard to the temperature at which the drying of the plates should be effected differ as widely as upon the advisability or otherwise of admitting a current of air through the box during the operation. The drying should be completed as rapidly as possible from the commencement of the operation, care being taken that the heat never exceeds 50°C. Many plate-makers simply dry the plates in an open apartment—of course, only illuminated by a non-actinic light—simply placing the plates on a horizontal surface, which may be maintained at the temperature indicated by a water bath, a lithographic stone, or merely a cast-iron plate arranged in a suitable manner for heating from below. This method of drying is open to many objections: the surface of the plate is seldom free from dust, and the gelatine coating is too liable to irregularities from draughts admitted to the apartment during the process. They are more frequently dried in specially-constructed boxes provided with screws for accurately levelling the plates, and through which only a small circulation of air takes place. These boxes are usually rectangular in shape, the upright sides being of wood and the bottom of sheet iron. The lid is an open framework covered with a close orange or black cotton material, the whole standing upon four iron legs over a spirit or gas flame. In the upper part of the box a thermometer is fixed, about the centre of either the side or lid, in such a position that it may be readily observed without the necessity of opening the box. Strong horizontal iron bars are placed across at about the centre, and are provided with thumbscrews, upon which may be placed a plate of glass bearing a circular spirit level, by which means the plates may be levelled with the greatest accuracy. The sheet-iron bottom of the box being heated unevenly, it becomes necessary to mitigate this inconvenience as far as possible, which is easily done by covering the plate to a depth of about half-an-inch with dry river sand, over which should be placed tissue paper to keep down any possible dust.

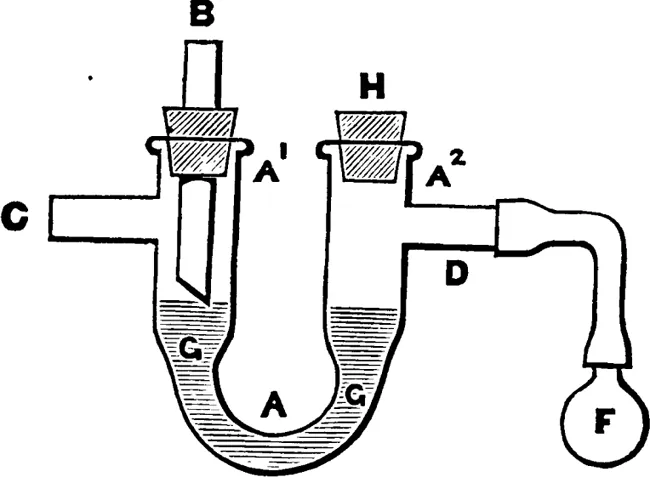

An Automatic Regulator of practical value is that devised by Ruegheimer. It consists of a glass tube, A, A1, A2. A1 is closed with an indiarubber stopper, through which passes a glass tube B, the lower end of which is cut off at an angle. It is attached to the gas supply pipe. The tube C is connected to the burners. To D is attached, by means of rubber tubing, a glass bulb F, which is placed inside the drying-box. G G is mercury, and H a rubber stopper by which the pressure on the mercury and quntiaty of air in F may be regulated.

Fig. 2.

The action of the instrument is obvious. The gas passes down B, over the surface of the mercury and by the tube C to the burner. On the bulb F reaching a certain temperature, the mercury will allow just sufficient gas to pass from the tube B to maintain the box at a given heat. If it should fall, the mercury recedes from the aperture of the tube B, a larger quantity of gas passes to the burner, and the temperature is restored to a normal degree. If the air in the ball F expands to too great an extent, the mercury rises, and would eventually entirely close the aperture and cut off the gas supply, unless the tube B is provided with a small hole acting as a by-pass. The tube B may be moved up and down through the rubber stopper at A1 as a means of adjustment.

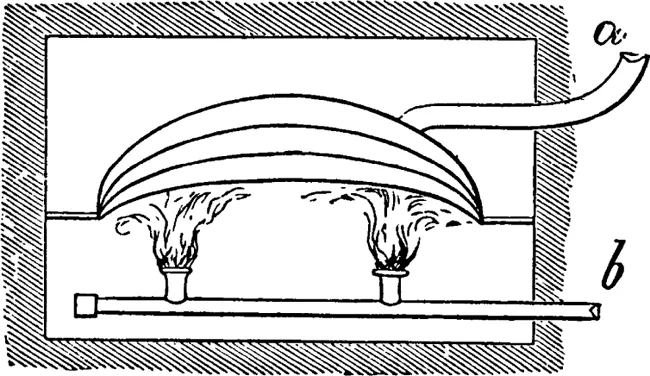

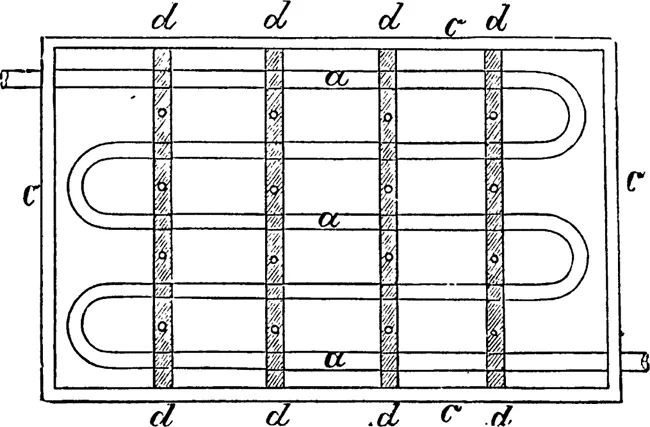

M. Thiel, of Paris, uses a very convenient drying-box, which, with his permission, is here explained. In a brick-lined receptacle under the laboratory floor lies the water-heating apparatus, which is constructed of sheet copper, and is capable of containing about four litres of water, utilised in the production of steam for heating the box. a, fig. 3, is the pipe passing through the wall into the drying-box; b is the gas supply pipe to the two atmospheric burners. Fig. 4 represents a plan of the drying-box; c c c c the perpendicular sides of the same. a a a gives a plan and position and arrangement of the earthenware heating pipes lying in a serpentine form at the bottom of the box, entirely covered with dry sand, and this again covered, as before described, with tissue paper. b is the outlet of the steam pipe. d d d d are movable horizontal iron bars with adjusting screws, on which the plates are levelled. The box is covered by a hinged lid, which is raised about a couple of inches during the drying to allow the air to circulate. The dimensions of the box will be determined by the size of the plates to be used, several of which may be placed side by side. Its height is about half a metre inside, and the plates are placed about its centre.

Fig. 3.

Fig. 4.

Glass Plates, to be used for printing from, must as a first consideration have their surfaces ground quite true and parallel. Since the introduction of special collotype presses requiring less pressure, the thickness is of less consequence than formerly, but for convenience of handling and to withstand the necessary pressure, in the printing frames, plates of at least four millimetres in thickness are desirable. Many use them from 8 to 10 millimetres in thickness; this, in the larger sizes, means a weight both inconvenient and difficult to handle. It is probably easier to work upon plain glass surfaces, and since means have been discovered of causing the chromated gelatine to adhere to polished glass with sufficient tenacity to produce several hundred impressions, the employment of ground glass plates is much more a matter of choice, than formerly. The ground surface, however, assists the formation of a grain in the case of thin layers, and the operation of grinding serves to remove accidental scratches from the surface of the plates. As in practice these damages constantly arise, it will in the long run be found both desirable and economical to employ the ground plates.

Ink Rollers are also of great consequence in both collotype and lithographic operations. For printing from stone leather rollers have always been exclusively employed, and they are still used in some collotype establishments, more particularly where hand presses are yet worked.

The Leather Roller consists of a wooden cylinder or stock of about 21 to 42 cm. in length and 9 to 11 cm. in diameter, with handles at either end, usually turned in one piece with the cylinder. Boxwood handles are sometimes let into the ends of the cylinder, but although smoother to work, they not infrequently work loose. In using these rollers the handles do not come in direct contact with the hands, but are covered with a protection of stout leather, which not only protects the printer’s hands from heating, but enables him by a heavier or lighter grip of the handles to apply a heavier or lighter pressure of the roller—a point of great value in inking the plate.

The wooden stock of the roller is first covered with a double thickness of woollen material—flannel or Melton cloth—and over this is drawn the cover of calf-skin, flesh side outwards. The manipulation of the seam must be managed with extreme care, as any unevenness would render the roller useless. At both ends of the cylinder the leather projects, and is usually drawn tight with string or nailed on. There are two descriptions of leather rollers—smooth and coarse. The latter are only used to apply ink to the stone or plate, and then, with the smooth roller, the proper distribution of the ink is effected. For the latter purpose, in collotype, hard glue or indiarubber rollers are employed, being considered far preferable. When a leather roller is in good order, and its use has been thoroughly mastered, it is...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- I. Introductory

- II. Bichromates in Conjunction with Organic Substances

- III. Summary of the more important Printing Processes with Chromated Gelatine

- IV. Collotype Apparatus

- V. Chemicals and Materials for Collotype

- VI. Preparation of the Collotype Plate

- VII. Negatives suitable for Collotype

- VIII. Printing in the Press

- IX. Finishing and Varnishing Collotype Prints

- X. Other Collotype Processes

- XI. Failures in Collotype: In the Preparation of the Plates

- XII. Investigations on Collotype

- XIII. Collotype in Natural Colours

- XIV. Magic Prints

- XV. Photo “Glass” Printing

- XVI. Allgeyer’s Collotype Process

- XVII. Practice of Photo-Lithography

- XVIII. Autography

- XIX. Negatives for Photo-Lithography

- XX. Application of the Carbon Process to Photo-Lithography

- Appendix. Steam Presses