![]()

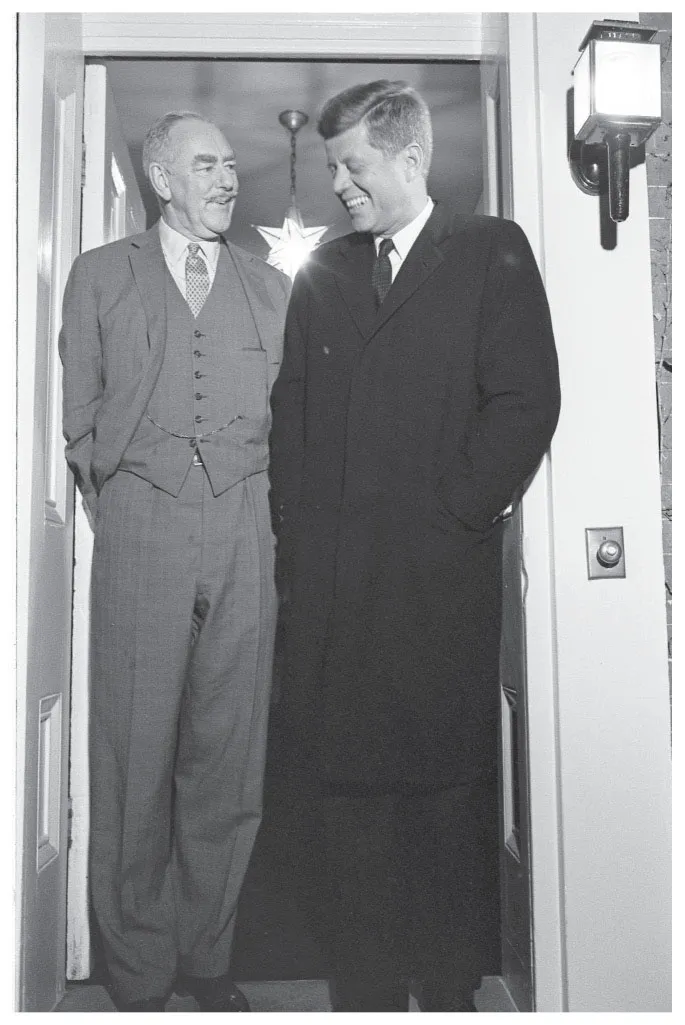

Dean Acheson with Jack Kennedy, on whose vitality WASPs preyed on in the era of their decline and fall.

ONE Twilight of the WASPs

demon duri…

durable demons…

—Dante, Inferno

In 1950 photographers from Life magazine descended on the ranch outside Santa Barbara to shoot pictures of the golden family. Francis Minturn “Duke” Sedgwick, heir to the Sedgwicks of Stockbridge, Massachusetts, had come to California from the East for the sake of his health, and on three or four thousand acres of tableland at Corral de Quati and, later, at Rancho La Laguna he created a kingdom of his own, one in which he could raise his family in seclusion from the world. “It was just paradise,” his oldest child, Alice, who was known as Saucie, said. “My parents owned the land from horizon to horizon in every direction…. Imagine a situation like that where nobody entered who wasn’t invited or hired!”

Her father was a figure of enchantment. He rode out each morning on Gazette, a dappled gray mare, or Flying Cloud, a pale strawberry roan, and was four hours in the saddle, herding his cattle. The thick, close-cropped hair, the strong, smooth-shaven jaw, the brilliant smile that blazed out of the dark tan—Francis Sedgwick was an extraordinary physical specimen. Yet the eyes, surprisingly in one so fair, were brown, and shone with an odd light—a glint of genius or mania. For Francis was no mere ranchero. “Fuzzy,” as his children called him, was in aspiration a Renaissance man. He painted, he sculpted, he even wrote fiction, and his little city-state on the Pacific seemed almost Greek in its beauty, suffused, Saucie said, with the light and feeling of the gods.

Yet for all that Fuzzy was cracked, a living exhibition of the corruption and decay of the WASP ideal. “After breakfast,” Saucie remembered, he would do “his exercises by the pool in this little loincloth he wore. It wasn’t a real jockstrap, but a neat little thing which looked more like a cotton bikini. He also did his writing there, sitting in the sun in this cotton bikini with a great big sombrero on his head. He was always nearly naked.” Fuzzy was neither the first nor the last WASP to think himself a Sun God, but he carried the fantasy beyond the bounds of propriety. He sent Saucie to the Branson School in Marin County, and when he came to visit her, the girls “stood at the windows and stared at him. He was so beautiful…” But they were soon disillusioned. Life might have been, as Saucie said, a cup her father was determined to drink to the dregs, but the life he desired was “raffish and violent.” He swaggered through it in oversized cowboy boots, and with his “enormous thorax” and the “muscles of his arms and chest and abdomen” he seemed, his daughter thought, a “priapic, almost strutting” figure. A bridesmaid in the wedding of another of his daughters, Pamela, was, on arriving at La Laguna, “immediately ushered into the presence of this ‘man,’ this father with his exaggerated views about human beauty. Nobody who wasn’t beautiful was allowed to be around. He began by making comments about each of the bridesmaids, the length of our legs, the size of our bosoms…. It was a stud farm, that house, with this great stallion parading around in as little as he could. We were the mares.”

He would choose a girl and invite her to his studio. “It was sort of like the emperor selecting a vestal virgin,” the bridesmaid shuddered as though at the recollection of a close escape from the Borgias. “We all knew we’d better not go. We all thought that this was against the rules… an eighteen-year-old and a fifty-year-old… no, no, no….” The man was “a fauve, a wild beast.” There “was something malsain”—unhealthy—about him, a “Marquis de Sade undercurrent that thirty years later I can feel in my flesh right now. The way he looked at people. He undressed every woman he saw. His eyes, they would just become cold.”

Francis Sedgwick’s seventh child, Edith Minturn, who was known as Weasel, Miss Weedles, or simply Edie, was appalled by her father’s predations. He would come “strutting out in a little blue bikini like a peacock,” Pamela’s bridesmaid remembered, to flirt with the schoolgirls. Edie was “wearing very short shorts, those long legs, and a man’s white shirt, a very thin girl with brown cropped hair, and she said something like, ‘Oh, for God’s sake, Fuzzy!’ ”

She was eleven or twelve at the time, “so thin, and suddenly she zipped off, just phftt, like that. It certainly didn’t deter him….” Another time she found her father “just humping away” in the blue room at La Laguna. It “blew her mind.”

Insulated from the noise and chaos of America—the vulgarity WASPs dreaded—Fuzzy waved his wand and created in the California hills an oasis instinct “with laughter and conversation,” the “life of Greek gods.” WASPs were always to chase a dream of rebirth, some improbable garden of Apollo; but in their decadence the dream became rancid. Once they had known how to make their desires productive, and bred leaders like Theodore and Franklin Roosevelt. Now, in characters like Francis Sedgwick, they were becoming mere headcases, Mayflower screwballs, the poet Robert Lowell called them, fit only for the asylum.

BABE PALEY KNEW WHICH WAY the wind was blowing. Her mother, Katharine Cushing, who was called “Gogsie,” had been ambitious of social distinction, and she had taken pains to ensure that her three daughters made brilliant marriages. The eldest, Mary, who was known as Minnie, married Vincent Astor. Betsey, the middle girl, married, first, Franklin Roosevelt’s son James and later John Hay “Jock” Whitney, who was senior prefect of Fuzzy Sedgwick’s form at Groton, the Massachusetts prep school, and afterward ambassador to the Court of St. James’s: one of the richest men in the United States, an American Duke of Omnium. Babe duly honored her family’s household gods and married Stanley Grafton Mortimer Jr., a Standard Oil heir. But she had the wit to perceive, as early as the 1940s, that the WASP ascendancy was rapidly declining toward the grave. WASP men were becoming so—dull; a woman wanted not a dud from the Social Register (somewhat oxymoronically known as the “stud book”) but energy, dynamism, the hairy back of the satyr. Babe readily divorced Mortimer and married a stallion, Bill Paley of C.B.S. She knew her horseflesh.

Paley, too, stood something to gain from the marriage. Few pleasures are more alluring to the founder of a new family than the caresses of a daughter of an old one, and even as Paley’s own career presaged the demise of the WASP establishment, he was enchanted by its style. Old blood, it is true, found his emulation of patrician manners a little forced. He attempted to recreate, at Kiluna Farm on Long Island, the elegant negligence of a Whig country house. But Lady Diana Cooper, who though descended from an English Tory family knew her Whig country houses, thought he tried too hard. Bill was, she said, “very attractive,” if “a little oriental,” as she delicately put it: it was his “luxury taste” that appalled her. She pretended that this was only because it embodied a standard “unattainable to us tradition-ridden tired Europeans,” who were used to things being shopworn (as if she envied Bill his tackiness). She made short work of the room in which she slept at Kiluna, with its little table “laid, as for a nuptial night, with fine lawn, plates, forks and a pyramid of choice-bloomed peaches, figs, grapes,” and its bathroom in which were to be found “all the aids to sleep, masks for open eyes, soothing unguents and potions.” (It was not done thus at Haddon Hall or Belvoir Castle.) But Lady Diana visited Kiluna Farm during the reign of Bill’s first wife, Dorothy; one of Bill’s motives in putting Dorothy away and installing Babe in her place was to have a consort whose taste was well-nigh faultless, for as Truman Capote observed, Babe had “only one fault; she was perfect; otherwise, she was perfect.”

She had been born, in 1915, in Boston, the youngest child of Harvey Cushing, the brilliant brain surgeon. Admired for her “willowy” figure, her “raven” hair, and the “classically perfect features” of her face (which had been carefully reconstructed after a 1934 car accident), she had endured a cynical upbringing. Her father was a good WASP, devoted to the care of others and the pursuit of knowledge, while earning a sensible income and achieving a notable professional reputation. But her mother, with a certain justness of perception, saw that good works by themselves never really cut it in WASPdom. One needed a fortune and a name.

Nothing short of tycoons would do for the girls, and Gogsie was not entirely pleased with Betsey’s marriage, in 1930, to Jimmy Roosevelt. For though the Roosevelts were socially at the top of the heap, their fortune was much smaller than those of their Hudson River neighbors, and the cash was entirely controlled by the family matriarch, Franklin’s mother Sara, a tightfisted old witch. Franklin himself was a charming man, but he was married to the eccentric Eleanor, who omitted to shave her armpits. On the other hand, when Minnie caught the eye of the disagreeable Vincent Astor, Gogsie was delighted at the prospect of a union with the Astor millions; and she all but dragged her daughter (who preferred artists to millionaires) to the drawing room of Heather Dune, her summer house in East Hampton, where the marriage took place in September 1940.

Babe, for her part, managed to be not wholly corrupted by Gogsie’s meretricious philosophy. After finishing school at Westover she became a respected editor at Vogue and was tempted to make a career of it. What was no less strange, she had, in spite of her success in the high-bitch world of fashion, a natural, unfeigned kindness. “Babe was a wonderfully warm human being,” Millicent Fenwick, one of her colleagues at Vogue and a future congresswoman, remembered: she would give you the coat off her back—in Millicent’s case a handsome gray squirrel that proved useful on a winter trip to London. Even such a potential rival as Gloria Vanderbilt conceded that Babe was “beautiful, kind, loyal.” For there was “nothing mean or hard” in her: she was “lovely, and slim, and gracious,” a creature “without envy or guile.”

WHAT BABE HAD, BESIDES DECENCY, was the WASP desire to rise above the Yankee passion for utility, to overcome the antipathy to graces that make life bearable. In this Bill Paley, with his plutocrat-gangster manners, could not help her, and at all events he soon lost interest in her and “abandoned her sexually,” though she was scarcely forty. He went back to his first love, C.B.S., and to flings with sundry women; she was left to manage the houses and head the best-dressed list. Yet even as she was consigned to this ornamental role, she was conscious of its vapidity. The fatuities of Women’s Wear Daily might suffice for Gogsie or the Duchess of Windsor, but Babe burned with a brighter flame, and lived her life in a way that suggested that opulence, when governed by taste, could raise life to a higher and nobler plane, as it had done in the courts of the Renaissance in an age that knew nothing of Women’s Wear Daily.

She never quite lived up to it; her houses lacked the ease of their Old World models. Too much facile elegance, they said, too many ambitious pains: Babe fretted not only over the taste of the food served on her plates, but the colors, as though she were Poussin at work upon a canvas. She wanted to be her own “living work of art,” yet even before lung cancer got the better of her she knew all the fatigues of her class in its last decay.

It was Truman Capote who supplied the fresh infusion of plasma. A “not unpleasant little monster,” the man of letters Edmund Wilson said, “like a fetus with a big head,” Capote acted the witty Shakespearian fool in the courts of those whom he styled, not altogether in irony, the Beautiful People. From the moment he met Babe, on Bill Paley’s airplane as it was about to take off for Jamaica, he was beguiled by her, and she, for her part, was liberated by his conversation, a stream of insinuating talk.

But it was not simply the venom of his gossip or even the patience with which he helped her to read Proust that drew her to him. The strange, androgynous creature with the “campy high-pitched Southern whine,” punctuated by shrieks and giggles, renewed her faith in herself. For something had gone out of the WASPs; they had lost the tranquil confidence of their forebears, the easy mastery that characterized the Roosevelts in statecraft and Edith Wharton and Nannie Cabot Lodge in style. The Depression and two World Wars leveled the playing fields, and in their decline WASPs found themselves drawn to outsiders on whose vitality they could feed. In the vampiric phase of WASPdom, white-shoe institutions that once shunned strangers (anyone not of the old tribal connection) turned to them for the lifeblood that might reanimate their order. In the same way Babe Paley turned to Truman Capote: here was an impresario who could do for her something akin to what Proust did for Countess Greffulhe, the forgettable airhead who attained immortality as the Duchesse de Guermantes in Remembrance of Things Past: make her interesting to herself.

The predator in Truman saw in Babe what others failed to see, that living a life so effortlessly perfect was, in fact, hard work, and bred its own unhappiness. Wherever Babe appeared flashbulbs popped and admirers fawned. Her clothing, her jewels, her flat in the St. Regis, her gardens at Kiluna, her tropical pavilion at Round Hill, provoked astonishment and envy. Her royal progresses, undertaken with her fellow Beautiful Persons, were lavishly reported in the press; now she lay, in luxurious indolence, amid the beaten gold of Gloria Guinness’s yacht as it sailed in the Aegean, now she steamed up the Dalmatian coast with Marella Agnelli, the countess of Fiat. Yet of all the jeweled beauties who constituted her set, it was she who obtained a peculiar eminence, unrivaled until the appearance of Jacqueline Kennedy. “She might have been painted by Boldoni or by Picasso during his Rose Period,” gushed Billy Baldwin, who helped her to furnish her houses. “So great is her beauty that no matter how often I see her, each time is the first time.”

But the goddess was unable to believe in her cult. What she needed, Truman saw, was a priest, one who would tend the altars, maintain the mysteries, furnish the texts. It was an office he was himself only too happy to fill. (It is believed that he supplied Babe with that beatitude of her class, “You can never be too rich or too thin.”) Amid the clouds of incense that wafted from his thurible, she could momentarily forget that she was merely another creature of WASP decadence, sunk in the vanities of café society. She could see herself as he saw her, a palm-nymph cast out of an Assyrian garden, a blithe spirit who could “fly where others walk.” Once this sense of superiority came easily to WASPs; now they needed help.

“MY GOD, THE FATHER WAS something! A cross between Mr. America and General Patton.” But Fuzzy Sedgwick’s machismo was deceptive; so exaggerated a masculinity had its origin not in strength but in a dread of weakness and effeminacy. He had been born, in New York City, in 1904, and had grown up a sickly, delicate child; he passed much of his life in the shadow of men much stronger than he himself was. His older brother Minturn was a natural athlete who played for the only Harvard team to win a Rose Bowl. “This boy doesn’t need a nanny,” the family doctor said at Minturn’s birth. “He needs a trainer.” Francis was a much slighter figure—“he just didn’t have the physique”—and though avid of athletic distinction, he “...