- 176 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

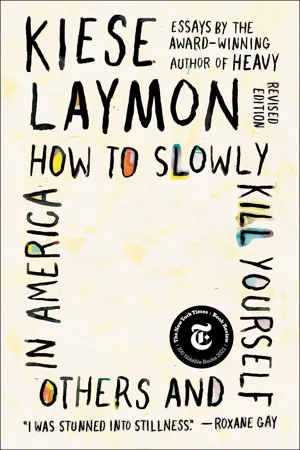

A New York Times Notable Book

A revised collection with thirteen essays, including six new to this edition and seven from the original edition, by the “star in the American literary firmament, with a voice that is courageous, honest, loving, and singularly beautiful” (NPR).

Brilliant and uncompromising, piercing and funny, How to Slowly Kill Yourself and Others in America is essential reading. This new edition of award-winning author Kiese Laymon’s first work of nonfiction looks inward, drawing heavily on the author and his family’s experiences, while simultaneously examining the world—Mississippi, the South, the United States—that has shaped their lives. With subjects that range from an interview with his mother to reflections on Ole Miss football, Outkast, and the labor of Black women, these thirteen insightful essays highlight Laymon’s profound love of language and his artful rendering of experience, trumpeting why he is “simply one of the most talented writers in America” (New York magazine).

A revised collection with thirteen essays, including six new to this edition and seven from the original edition, by the “star in the American literary firmament, with a voice that is courageous, honest, loving, and singularly beautiful” (NPR).

Brilliant and uncompromising, piercing and funny, How to Slowly Kill Yourself and Others in America is essential reading. This new edition of award-winning author Kiese Laymon’s first work of nonfiction looks inward, drawing heavily on the author and his family’s experiences, while simultaneously examining the world—Mississippi, the South, the United States—that has shaped their lives. With subjects that range from an interview with his mother to reflections on Ole Miss football, Outkast, and the labor of Black women, these thirteen insightful essays highlight Laymon’s profound love of language and his artful rendering of experience, trumpeting why he is “simply one of the most talented writers in America” (New York magazine).

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access How to Slowly Kill Yourself and Others in America by Kiese Laymon in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & African American Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

MISSISSIPPI: AN AWAKENING, IN DAYS

DAY 1

22 Americans are dead from coronavirus, and Donald Trump tweets, “We have a perfectly coordinated and fine tuned plan at the White House for our attack on CoronaVirus.”

I hear from Joe Osmundson, writer, friend, and scientist, that I should not attend the Association of Writers Programs, a conference I say I am too tired to attend, a conference where I will not be paid for attending. “The government is way behind on this,” Joe writes. “Experts in our community are the best we have. I’ve been talking to a lot of friends working on this, and I trust them a lot.”

“Should I fly, fam?” I ask him.

“It’s not ‘US’ we’re doing this for,” he texts back. “The risk for you is still low, but it’s kinda like what do we owe our elders and the folks with compromised immune systems.”

“Thanks for this,” I write back. “I’ma sit my ass at home and not go to these other events on my schedule.”

These other events are paid readings I’m supposed to do in Ohio and West Virginia. These events are where I make most of my money. The first event in Ohio is sold out, but I tell myself that I’m sure they’ll postpone before the tenth. I assume the same thing about West Virginia.

I am lonely. I am afraid.

And/Yet/But/Somehow I drive to the casino in Tunica, Mississippi, one of the poorest counties in the United States, and lather my hands in sanitizer.

It could all be so much worse.

DAY 2

31 Americans are dead from coronavirus, and after meeting with Republican leaders, Donald Trumps says, “It’s about twenty-six deaths, within our country. And had we not acted quickly, that number would have been substantially more.”

These paid events I am booked to attend have yet to be canceled. It took Grandmama, the person who will get most of the money I make for these trips, a year working in the chicken plant to make the kind of money that awaits me for these two events.

Grandmama is one of the elders Joe talked about. She is a ninety-year-old Black woman from Mississippi, and her immune system is severely compromised. She believes she is still alive because of hard work and Jesus Christ.

I have my agency tell the folks in Cincinnati that I will not under any circumstance be signing books or shaking hands at the event.

We all have to be safe.

Later that night, I sign books. I shake hands. I hug people. I feel love. I lather my hands in sanitizer. A monied man at the event gives me a ticket to see Lauryn Hill, who is also in Cincinnati. I tell organizers of the event that I’d rather go to the Lauryn Hill show than go to dinner.

I skip Lauryn Hill.

I skip dinner.

I congratulate myself on skipping both, on looking out for elders, and people like my Grandmama with compromised immune systems.

It could all be so much worse.

DAY 3

38 Americans are dead from coronavirus, and Donald Trump says, in his address to the nation, “The virus will not have a chance against us. No nation is more prepared or more resilient than the United States.”

I am outside of my hotel in Cincinnati, waiting for a car service to drive me to Marshall, West Virginia. When the lanky old white man with large knuckles pulls up, I place my bags in his trunk. I do not shake his hand. Neither he nor I have on a mask or gloves. I am headed to West Virginia to get this money in the backseat of a new black car driven by an old white man.

I lather my hands in sanitizer.

Barely out of Cincinnati, the driver tells me he is a preacher. We talk about his church, his calling, his time living in the Bronx, his wife’s abusive upbringing, all the powerful men he’s driven place to place. He stops talking for a bit, and I look at the land we’re zooming by. I am a writer. I should be writing about land I’ve never seen. I lather my hands in sanitizer, open my phone to type a sentence.

“It could all be so much worse,” I write.

I get to West Virginia two hours before I’m supposed to have dinner with the organizers of tonight’s event. Kristen walks me from the hotel around the corner to the restaurant. There is a long table of around ten folks already sitting down.

“How y’all doing?” I ask, faking a laugh. “I guess we’re not doing handshakes, huh?”

I am forever a fat Black boy from Jackson, Mississippi. I hate to be trapped in white places where I do not know anyone Black. My mama and Grandmama rarely sit with their backs to doors. I choose the seat at the end of the table, next to a young brother whose hairline makes me remember Mississippi.

Under the table, I lather my hands in sanitizer.

I am sitting across from two powerful white people whose rhythms I cannot pick up. I cannot tell when they will laugh, when they will fidget. I cannot tell if they have actually laughed or fidgeted. The white woman in front of me does not want to be there. I find out that the university is preparing to suspend in-person classes and begin distance learning.

No one is coming to this reading tonight, I tell myself. That’s definitely for the better, as long as I can still get my check.

I order a Thai cauliflower wrap and fries. There is no way I’m eating that wrap. Or the fries.

I have eaten all but one of the fries when the brilliant brother with the familiar hairline offers me some sanitizer.

“You think we could shake hands now?” he asks.

“Oh absolutely,” I say, and shake the hands of all the incredible students, thanking everyone for wanting to come out in such a scary time.

I ask for a to-go box for my wrap and say that I hope to see y’all at the reading. On the way to the reading, I stop back by the hotel because I don’t need my backpack smelling like old cauliflower. White people treat Black people who smell like old cauliflower like Black people.

I’m scared. I’m tired. I’m lonely. I need my check. I don’t want to be treated like a Black person by white people while trying to dodge coronavirus.

It’s hot in my room. I’m sweating way too much. I take off the shirt beneath my Meager hoodie. It’s drenched. I place the cauliflower wrap on the counter.

I think I have coronavirus.

Or I’m just fat. Or I’m just nervous.

I think I have coronavirus.

I get to the venue. The white woman who greets me walks with a limp. I walk with a limp. She kindly takes me to the green room. A gentle tall white man knocks on the green room door and pulls out a huge bottle of sanitizer.

“Your agency told us you needed this.”

“Oh wow,” I say, trying to act like I had no idea. “That’s weird. Thanks.”

After the reading, some of the astounding students whom I had dinner with come on stage and ask me to sign their books, take pictures, shake hands. I sign their books, take pictures, shake hands. I walk out to the foyer, sit at a table, and sign more books. After all the books are signed, I walk out and meet the gentle tall white man who gave me the sanitizer. He is going to be taking me back to my hotel in his truck.

We talk about coronavirus. We talk about Randy Moss. We talk about Jason Williams. We talk about coronavirus.

As we get to my hotel, I’m wondering whether I’m supposed to shake his hand since I’m convinced both of us have coronavirus.

The tall gentle white man keeps both hands on the steering wheel and tells me bye.

“Thanks,” I say out loud.

My room smells like old cauliflower. I take two showers, lather my hands in sanitizer, and I try to dream.

DAY 4

40 Americans are dead from coronavirus, and Mississippi governor Tate Reeves is cutting short his European vacation because of Donald Trump’s European travel restrictions.

At five in the morning, another white man picks me up to drive me to the airport. He does not speak. I give him a big tip when he drops me off. He holds the money like I’d hold a boogery Kleenex given to me by a white man driving me to an airport.

“Thanks,” I say out loud.

I am wearing a black hoodie, a black hat, a black Bane mask, black headphones. Hanging around my neck are two dog tags. One, a quote from James Baldwin, says, “The very time I thought I was lost my dungeon shook and my chains fell off.” The other, a quote from Lucille Clifton, says, “they ask me to remember but they want me to remember their memories and i keep on remembering mine.”

I take a selfie on the plane and place it on Instagram with the caption: “Strange times when you have to be on the road to make money to help care for a miraculous 90 year old woman who you won’t be able to touch for 14 days… Kindness. Tenderness. Generosity. We can do this.”

Fourteen days, I tell myself. It could all be so much worse.

“The virus will not have a chance against us,” Donald Trump says later that afternoon.

DAY 5

413 Americans are dead from coronavirus, and Donald Trump will not say, “I am sorry.”

Governor Tate Reeves decides that the one abortion clinic in Mississippi is not an essential business that should remain open, but gun stores are. I’ve written around Tate without saying Tate’s name for eight years.

In college, my partner, Nzola, and I got into an altercation with two fraternities on Bid Day. Some fraternity members wore Confederate capes, Afro wigs, and others blackened their faces. I’ve written about how they called us “niggers.” I’ve written about how they called Nzola a “nigger b—.” I’ve written about that experience and guns. I’ve written about that experience and bats. I’ve written about that experience and how my investment in patriarchy diminished Nzola’s suffering.

I have never written about the heartbreak of seeing the future governor of Mississippi in that group of white boys, proudly representing the Kappa Alpha fraternity and its Confederate commitment to Black suffering. I have never admitted that after playing basketball against Tate all through high school, and knowing that he went to a public school called Florence, not a segregation academy, like so many other white boys we knew, it hurt my feelings to see Tate doing what white boys who pledged their identities to the Old South ideologies were supposed to do.

When I saw Tate in that Confederate cacophony of drunken white boyhood, doing what they did, I knew he could one day be governor of Mississippi and President of the United States.

That is still the most damning thing I can ever say about a white boy from Mississippi.

DAY 6

9,400 Americans are dead from coronavirus, and Donald Trump will not say, “I was wrong.”

Mama is scared because the nurse we pay to take care of Grandmama will not wear her mask for fear that it could hurt my Grandmama’s feelings.

I am scared because Mama will not stop going to work. She sends me a eulogy she wants me to read if she dies. The eulogy confuses me. There is so much left out. She wants people to know her dream was to be of use to the world, and particularly Mississippi. But the eulogy is more about the places Mama has been than the justice work she’s done. I do not argue with Mama. I tell her that if she dies before I die, I will read the eulogy as it is written.

It could all be so much worse.

I get an email from the writer Cherry Lou Sy, saying that one of those dead 9,400 Americans is my former student Kimarlee Nguyen. Kimarlee and I shared a classroom at Vassar College. Long before she was my student, Kimarlee would greet me with this raspy offering:

“Yo, Kiese!”

When we finally shared a classroom, I was unable to adequately protect Kimarlee from the phantoms haunting most American classrooms. Phantoms need hosts. Many white hosts need phantoms. These phantoms encouraged Kimarlee to write her Cambodian self out of her writing. They disciplined her for not erasing her family’s rememories of Khmer Rouge.

Kimarlee accepted her sadness, her fatigue, her anger, and then along with James and Charmaine, she willed herself to write more deeply into the historic imagination of ancestral spirits.

I always assumed coronavirus would take my Grandmama, my mama, my aunties, my friends, me, possibly in reverse order.

I never ever assumed it would take my students.

DAY 7

104,051 Americans are dead from the coronavirus, and Donald Trump will not say, “I am sorry.” After Darnella Frazier, a seventeen-year-old Black girl from South Minneapolis, courageously films police executing a survivor of coronavirus named George Floyd, and Breonna Taylor, an EMT tasked with aiding those with coronavirus, is shot by police five times in her own house, uprisings begin in the United States.

The week before savvy, young, mostly Black folks longing to breathe and break fill Jackson, Mississippi, streets, a lone white Jewish teacher in Oxford, Mississippi, cuts his hands and places bloody handprints all over the biggest Confederate monument on the campus of “Ole Miss.” The Jewish brother spray-paints “spiritual genocide” on all four sides of the monument before being arrested.

Instead of covering the monument, workers are told to cover “spiritual genocide” with what looks like swaddling cloth.

I help bail the Jewish brother out. I help bail out folks in Mississippi, in Minneapolis, in Louisville.

I go home alone.

I am forty-five years old, the exact age Grandmama was when I was born. Just like Grandmama at forty-five, I live alone in Mississippi. Yet unlike Grandmama, I have no children, no grandchildren. I own no land, no garden, no property, and I am afraid of walking in my neig...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Epigraph

- Author’s Note #2

- 1. Mississippi: An Awakening, in Days

- 2. What I Pledge Allegiance To

- 3. Da Art of Storytellin’ (A Prequel)

- 4. How They Do in Oxford

- 5. Hey Mama: An Essay in Emails

- 6. Echo: Mychal, Darnell, Kiese, Kai, and Marlon

- 7. Daydreaming with D’Andre Brown

- 8. You Are the Second Person

- 9. Hip-Hop Stole My Southern Black Boy

- 10. Our Kind of Ridiculous

- 11. How to Slowly Kill Yourself and Others in America

- 12. The Worst of White Folks

- 13. We Will Never Ever Know

- A Note on the Author

- Copyright