- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Future Trends For Top Materials

About this book

This reference focuses on defined types of compounds which are of interest to readers who are motivated to explore basic information about new materials for advanced industrial applications. General and established synthetic methodologies for several compounds are explained giving a straightforward approaches for researchers who intend to pursue new projects in materials sciences. This book presents 9 chapters, covering phthalocyanines, polymethines, porphyrins, BODIPYs, dendrimers, carbon allotropes, organic frameworks, nanoparticles and future prospects. Each chapter covers detailed synthetic aspects of the most established preparation routes for the specific compounds, while giving a historical perspective, with selective information on actual and outstanding applications of each material, unraveling what likely might be the future for each category. This book is intended as a hands-on reference guide for undergraduates and graduates interested in industrial chemistry and materials science.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Carbon Allotropes as Top Materials

Mário Calvete

Abstract

INTRODUCTION

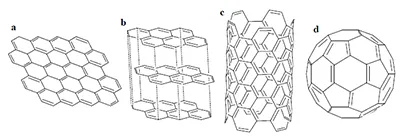

(a) graphene; (b) graphite; (c) carbon nanotube; (d) fullerene.

Table of contents

- Welcome

- Table of Contents

- Title Page

- BENTHAM SCIENCE PUBLISHERS LTD.

- FOREWORD

- PREFACE

- BIOGRAPHY

- Phthalocyanines as Top Materials

- Polymethines as Top Materials

- Porphyrins as Top Materials

- BODIPY Dyes as Top Materials

- Dendrimers as Top Materials

- Carbon Allotropes as Top Materials

- Organic Frameworks as Top Materials

- Nanoparticles as Top Materials

- Future Prospects

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app