![]()

LAND VALUE TAXATION

![]()

15

The Single Tax and Laissez Faire

Henry George’s attempt to remove the destabilising elements in the economy was a direct challenge to the distribution of power and patronage. That was why it was very necessary for the diehard enemies of the left and the right to take time off to attack him as a common foe, for he threatened their cosy entrenched interests.

On the right, landowners (indiscriminately categorised as ‘capitalists’) attacked George as a ‘socialist’ and ‘communist’. Associating themselves with the attempt to discredit the American economist, the socialists, including Marx, sought to denigrate and dismiss George as an apologist for the capitalist system. This unholy coalition is the best proof that George held no brief for either of the conventional orthodoxies; that he in fact offered a genuine alternative to those which, through fair trial and repeated error, had successfully discredited themselves.

Henry George did not fit neatly into any of the established categories of political philosophy. He insisted that the private creation of wealth meant that capital could be individually owned. This located him on the right, in Marxist terms. Marx placed the burden of blame for the excesses of 19th century industrial society on capital (hence the title of his book, Capital). But George’s uncompromising stand against the individual appropriation of the socially-created value of natural resources alienated him from the right, and appeared to lend some force to the argument that he was a socialist.

He did suggest that a full tax on land values, aligned with the removal of taxes on other sources of income, would produce a society that could be called socialism. But he was not an anarcho-socialist (it was Marx who proclaimed ‘the withering away of the state’). George saw a continuing but benign role for government, which would collect land values and spend them for the collective good of the community.

We should reach the ideal of the socialist, but not through government repression. Government would change its character, and would become the administration of a great co-operative society. It would become merely the agency by which the common property was administered for the common benefit.

Even so, George was closer to the capitalist, for he ardently advocated the virtues of the free market (which, if permitted to operate freely, was nothing except the neutral mechanism for expressing the totality of preferences of people as consumers and wealth creators). He located the fundamental obstacle to this model in the land tenure system. Winston Churchill was to echo his critique in these terms.

It is quite true that land monopoly is not the only monopoly which exists, but it is by far the greatest of monopolies — it is a perpetual monopoly, and it is the mother of all other forms of monopoly.

Churchill, as President of the Board of Trade, delivered this scathing commentary on the Tory land monopolists at the hustings. He employed his oratorical talents to inform the people that ‘the unearned increment in land is reaped by the land monopolist in exact proportion, not to the service but to the disservice done’. Churchill had no doubt how profoundly evil landlordism was and how it affected the economic system.

It does not matter where you look or what examples you select, you will see that every form of enterprise, every step in material progress, is only undertaken after the land monopolist has skimmed the cream off for himself, and everywhere today the man or the public body who wishes to put land to its highest use is forced to pay a preliminary fine in land values to the man who is putting it to an inferior use, and in some cases to no use at all. All comes back to the land value...

But was Henry George trying to get the best of both worlds ? Was he utopian ? Did he create a vision of a Great Society which could never be realised ? No. His reforms were not so impractical and abstract as to safely enable people of all political persuasions to pay lip-service to the ideals while conveniently pursuing other courses of action.

George made great claims for the one major fiscal reform that he advocated. A single tax on land values was to accomplish more than income redistribution. It was also intended to lay the foundations of an enhanced moral and social life. Was he over-stating his case? In building up our examination of the charge that he was utopian, we must begin with single issue problems and then work up to the total picture. To this end, we can take as an issue a major contemporary problem, the quality and availability of housing.

Sociologists and psychologists have now documented sufficient evidence for us to take it as proven that poor housing contributes to a deterioration in both family life and the behaviour of individuals who are relegated to slums. Most societies aspire to the provision of good-quality homes for all their citizens in the belief that this is a human right. Yet this goal eludes even the technologically most advanced economies, which have the potential capacity for making such provisions. Can we seriously claim that by eliminating a tax on capital improvements, and offsetting the loss in revenue by raising the income from land values, we would achieve this aspiration? We do not have to rely on theory for an answer. The empirical evidence suggests that this one simple reform would, indeed, make a measurable contribution to the achievement of decent accommodation for every family.

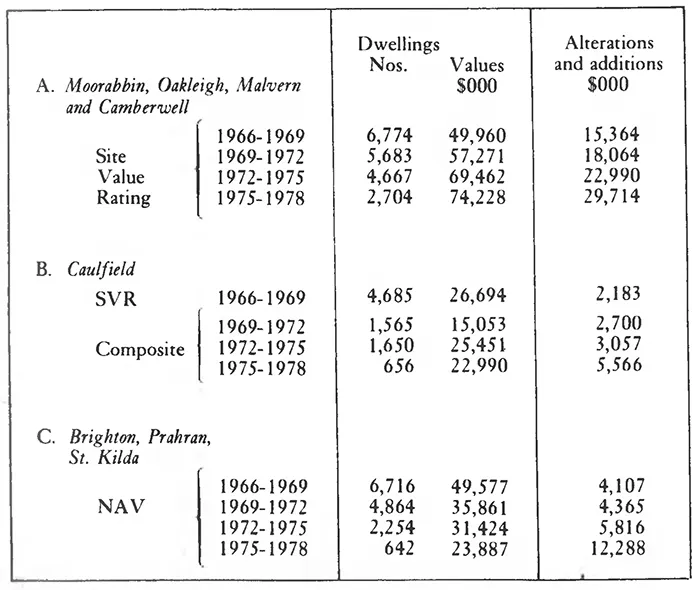

The Australian state of Victoria between the years 1966 and 1978 can be taken as a case study. Twenty-seven metropolitan cities used site value rating (SVR: represented in Table 15:I by Moorabbin, Oakleigh, Malvern and Camberwell). Fifteen cities based their local property tax on the net annual value (NAV) of both land and buildings. These cities are represented by Brighton, Prahran and St. Kilda. Before analysing the story as summarised in the statistics, we should note that 1973 saw the peak in the cycle of land values.

TABLE 15:I

Victoria Metropolitan Cities, 1966-1978

Numbers and values of building permits issued in selected cities grouped according to rating basis

Between the censuses of 19 71 and 1976, the number of new dwellings built by private enterprise increased on average by 12.9% in the 27 cities that taxed only land values. In the 15 cities that also taxed buildings the average growth in dwellings was a mere 2.8%; eight of these cities showed decreases in their total dwellings.

Because of the escalating price of land in the early 1970s, the absence of a tax on buildings in the S VR cities was not sufficient to offset the effects on the house building programme. The land price boom pushed the price of completed homes beyond the reach of many aspiring owner-occupiers, and the construction of new houses declined. The drop, however, was far less marked in the SVR cities than in the NAV cities. In 1975-78, the number of building permits issued was 39.9% of the 1966-69 figure for the SVR cities; but the comparable figure for those areas that taxed buildings was 9.5%.

So, as people were priced out of the house-buying category, they turned to renovating older properties, and ‘making do’ with their existing homes. Not surprisingly, the value of improvements trebled in the NAV cities, while they only doubled in the SVR cities. This was because more people in the latter areas were able to buy their way into the quality of homes that they desired: they were not deeply locked into their homes. This fact is verified by the value of new dwellings: the figure increased dramatically for the SVR areas, whereas they slumped badly in the NAV cities.

Caulfield is interesting because it illustrates what happens when a city shifts its property tax onto buildings. The city is one of eight predominantly residential cities. The other seven surround or adjoin it, and are the ones identified in Table 15:I. It can, therefore, be fairly compared with its neighbours.

In 1969-70, Caulfield switched from the site-value basis to the ‘composite' basis of taxation (popularly known as the ‘shandy' system) under which half of the rates are on site value and half on the value of land-plus-improvements. The immediate consequence was a dramatic drop in the number of building permits sought by developers. Although building permits issued for 1969-72 dropped by 16% over their level in the previous period for the SVR cities, they dropped by 66% in Caulfield. This sensitivity to the property tax has been traced in other urban areas in Australia. Usually, however, the marked change has been in the opposite direction; with the progressive untaxing of buildings by local authorities switching to site value rating, there have been sudden increases in the number of applications for building permits.

The second point to note about Caulfield relates to the value of building permits. The composite tax system is in an intermediate position between SVR and NAV. This is reflected in the figures for the value of building permits, which were worse than for the SVR cities but better than for the NAV cities.

The dramatic lesson to be derived from this is that if a government wishes to encourage new construction, it needs to shift the burden of taxation onto land values. If a government is perverse, however, and wishes to stifle housebuilding and the quality of the physical environment of its citizens, it should retain — or shift to — a system of property taxes that penalises capital improvements upon the land, the normal practice in the West.

This conclusion would not go unchallenged, however. Homer Hoyt would claim that the loss of profit from land would destroy rather than rejuvenate the construction industry. Coming from such an authority, this is a serious challenge that requires scrutiny.

Hoyt’s contention is that developers rely almost exclusively on the increase in the value of land to turn a project into an economically viable one. 'If the full increase fin the value of the land] were taxed (single tax) the developer would have no incentive to build a shopping centre, or to build houses, offices, etc. He would make a profit on sale of houses but I doubt that incentive would be enough,’ wrote Hoyt.

Hoyt’s argument rests on the assumption that landowners sell their land for less than the full economic rental value capitalised into the highest selling price that the market will bear. It may be that, in some cases — because of imperfections in the market — landowners sell for less than the full residual value of a project after all the development costs (including the developer’s normal profits) have been taken into account. In such cases, the developers — the capitalists — enjoy a bonus; they reap some of the economic rent that would normally go to the land monopolist. But would the developer be willing to pay the full economic rent for the opportunity to engage in a viable commercial project? ‘In principle he will be prepared to have to pay it all: competition within the development industry will drive developers’ profits down to the normal rates for entrepreneurial endeavour. This theory is supported empirically.’ This conclusion has been authoritatively endorsed recently by British ministerial advisors. What the evidence amounts to is that developers are already paying the full land tax — the beneficiaries, however, being the land monopolists rather than the community. Landowners capitalise that portion of economic rent that is not already taxed by government, and impose the levy on final consumers through the construction industry.

It would be fair to say that Homer Hoyt understands these facts. When he wrote to the present author that ‘My large vacant tract near Washington is being developed and houses are selling rapidly at peak prices’, he did so not as developer but as landowner. It is inconceivabl...