![]()

![]()

Chapter 1

Why This Matters

Black Women Deserve to Be Free

In the foyer of her mother’s church, a dark-skinned, beautiful little girl was surrounded by a small crowd of adults who were all laughing, amused by her three-year-old antics. She was delighted by the attention. It felt natural to be at the center of so much love and joy, without effort. One of the adults—a very tall man—picked her up and tossed her into the air multiple times, a little higher each time. She squealed loudly with each toss and would throw her head back to see just how close to the ceiling she was. Every time his hands left her little body for a few seconds, it felt like she was flying. Beneath her was the crowd of adults who wouldn’t let her fall, a circle of smiling faces cheering her on and sharing in her joy. She felt like she could do this forever. Her loud squeals eventually brought out her mother, who was curious to see why her daughter was laughing so hard. Her mother’s worry shut down the action quickly. She demanded that no one toss her daughter that high up in the air again. The little girl was immediately returned to the ground and picked up by her mother who hurriedly made her way to the car.

That little girl was me. This is my earliest memory, fuzzy around the edges but one that makes me smile with all my teeth whenever I remember it. For many years I forgot about this version of myself. I still forget her sometimes. When asked about my childhood, the parts that immediately come to mind are the experiences of loneliness, of trauma, of carrying more knowledge of the world’s horrors than I should have known at such a tender age. My mother describes it like an on-off switch—one day I was full of joy and laughter, and the next I had withdrawn into myself, quiet and terrified of the world. Those difficult experiences shaped me; they formed the way I showed up in friendships, relationships, and even in my own family.

I grew up too fast, and internally I mourned the loss of a “normal” childhood where I could just be a little girl with no cares in the world. Externally, adults praised me for being so mature for my age. I wasn’t a child who showed her anger on the surface, but I felt red-hot rage every time an adult congratulated me for wearing my pain well instead of offering to help remove the heavy burden that wasn’t mine to carry in the first place. I would come home and complain to my mother about how much I hated being called mature, and she would laugh, perplexed by why I was so offended by a compliment. I didn’t have the language then to explain to her why it hurt so much. Even as an adult, I still feel a less intense version of that rage when I am praised for being “so strong and brave.” In my head, I am often yelling at the person complimenting me: “I don’t want to be strong. I don’t want to be wise beyond my years. I want the freedom to be soft without fear.”

But being seen as mature or wise had its gifts too. It gave me a role to play in relationships that offered something of value. I could offer the wisdom from the lessons I had learned while keeping my own vulnerability around the pain safely tucked away inside of me. Being seen as brave or strong meant I got a level of respect not offered to those who were perceived as fragile or weak. I had been criticized so often as a child for being too sensitive, so being praised as strong felt like I had successfully fooled everyone into seeing only the parts of me I allowed them to see. No one needed to know how much everything actually affected me, how badly I wanted to feel loved without effort. The risk of pain was too great after all I had experienced, so I used what came naturally to me to try and earn love. Maybe if I was the bravest, wisest, most mature person in a room I would be worthy again of the attention, love, and joy that my three-year-old self received without effort.

I learned how to be “vulnerable” with people without really letting them see me. A part of me was always withdrawn as a mechanism of protection. “You can only hurt the parts of me I give you, and if I never give you all of me, some part of me will remain safe from pain.” From my withdrawn vantage point, I would observe people and their behavior. Because my family generally didn’t speak much around their experiences of pain, I learned to observe patterns, looking for what people weren’t saying underneath the many or few words they chose. I wanted to understand why people acted the way they did because it might help me understand why I had ended up the recipient of so much pain. Maybe it would help me understand what to do with the hurt, since it was unacceptable in my Nigerian culture to speak of your pain. Why did other people seem happier than me and my family members? Were they really happy, or was everyone carrying unspoken hurt around with them all the time too? If so, how would we all heal? Did we have to carry around the heavy backpacks filled with pain and suffering and trauma forever?

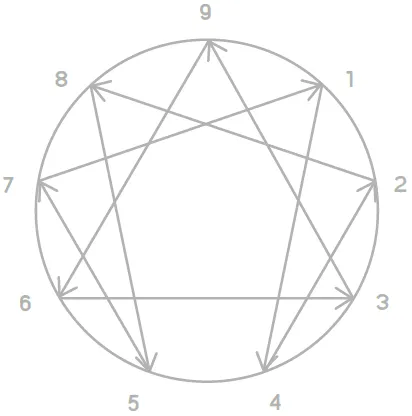

These questions led me to a master’s program in clinical mental health counseling at the age of twenty-four. I finally had the time and resources to live in the space of these questions and gain a better understanding of what motivates our behaviors, how our attachments shape us, how we become resilient, and how we heal. It was during my master’s program that I was first introduced to the Enneagram. At the time, I was a bit skeptical of the idea that all of human experience could be divided into nine types. Additionally, the person who introduced the Enneagram to me wasn’t someone whose suggestions I deemed trustworthy, so I tossed it out and forgot about it.

But over the next couple of years and through the end of my graduate degree, the Enneagram kept popping up everywhere for me. More and more people I respected were talking about it, and I was beginning to get curious about a system that seemed more dynamic and nuanced than other personality tests I had used up until that point.

The system of the Enneagram invited me to, for the first time, see how much of my energy went into creating an image that was separate from my truest self, what the Enneagram calls the essential self. Without shame, I was given language for the patterns I had noticed over the years, patterns I had come to think of as “just who I am.” I began to see how I had wielded the particular behaviors that gained me applause and acceptance into a kind of armor to keep myself safe from pain. The more I understood about my type as armor, the freer I felt to choose when to pick up and put down the armor without confusing it with my true identity.

The kindest gift the Enneagram has given me is a deepened compassion for myself and for others. Its invitation to notice my patterns without judgment and to allow myself to be exactly where I am was transformative for me. I had grown up with the belief that I needed to become a perfect future version of myself in order to be worthy of love, and the Enneagram taught me how to compassionately question that compelling yet untrue story about my lovability. I always felt like an anomaly within my family, my Nigerian culture, and the white American culture I was thrust into at the age of seventeen, so to discover a system that read me so perfectly felt like a relief. It wasn’t just me after all. As I continued to work with it, I found the permission to be present with my goodness, worthiness, and lovability in each moment. I embrace my humanity more now than I did before I began working with this transformative system.

Once I completed my master’s program, I began my training with the Narrative Enneagram to become a certified teacher and practitioner. The first return of that memory of three-year-old me being thrown in the air happened during a visualization exercise at an Enneagram training. My three-year-old self came back to me as an invitation, a reminder of what was true before the pain of the world clouded my ability to see it.

All of my life so far has been a journey to return to the freedom and joy of that little girl who knew she was deserving of love without effort. Those things I believed I had to be to survive are things that are actually true of me. I am brave. I am wise. I am strong. But what I have learned and continue to learn is that my bravery and wisdom aren’t what earn me love, belonging, or safety. The danger lies in confusing my strengths with my worthiness. When I do that, I abandon the other parts of myself that I’m convinced make me less worthy. In reality, I am worthy of love when I am doing absolutely nothing, when I am at rest, when I allow myself to be soft, when I am vulnerable, when I make mistakes or am anxious, angry, or sad.

The more space I create between my essential self and the things I learned to do to survive, the closer I feel to three-year-old me. Her freedom and joy don’t feel naive; after all, the world was still inequitable and unjust while she soared in the air protected by the circle of love beneath her. Her embodied freedom wasn’t grounded in the existence of a perfect world. My three-year-old self—a depiction of my truest self—reminds me that it is possible to embody freedom as a dark-skinned Black immigrant woman while so much pain still exists in an imperfect world.

Because of the way our world is set up, this sounds like a revolutionary concept. Blackness, whether on the continent of Africa or in the diaspora, is often associated with possessing superhuman strength, toughness, and a constant striving to prove we are not who the systems of supremacy tell us we are. Even when we attain success as defined by the systems of supremacy (material wealth, career recognition, fame, etc.), we still can’t shake the feelings of not-enoughness. We use protective armor—humor, hardness, or even lighter skin—to get further up the ladder of supremacy rather than in the pursuit of freedom.

On the other hand, sometimes even our work to dismantle systems of oppression can become the altar on which we place our worthiness, believing we are more worthy because we are fighting against oppression. Our activism can become another armor we carry that doesn’t lend itself to our true freedom and rest. But there is a difference between fighting to prove we are worthy and fighting to create a new world because we know we are worthy of it. When our fight is grounded in a belief in our inherent worth and dignity, we don’t have to carry the fight with us everywhere like armor. We are not here to just fight and suffer until we die. We get to choose rest, ease, and joy for ourselves. We deserve that even while the world is still a raging dumpster fire. We deserve that even while we work toward uprooting the lies of supremacy within us and around us. We deserve that simply because joy is our birthright. Rest is our birthright.

This book explores the Enneagram as armor that we wield to protect ourselves from pain and offers practices to help create more space between what we do to survive and who we are. This book is also a love letter to Black women in particular. Zora Neale Hurston wrote way back in 1937 that the Black woman is the mule of the world, and those words still ring true in 2021.1 Black women are often at the forefront of liberatory movements because if we don’t fight for ourselves, no one else will. And in the fight for our own liberation, we end up fighting for everyone else’s even when they don’t show up for us. We are dismissed as angry when we demand for people to do better. We are glorified for how well we suffer and applauded by the people who benefit daily from the systems that cause our suffering. We internalize the messages of those systems and punish ourselves for being too much and not enough at the same time. It is exhausting. We most certainly need armor to protect ourselves from the cruelty of this world, but we cannot forget that our armor is only a one-sided story of who we are. We need spaces, both internal and external, where we can exist without the armor.

So, dear Black woman, I hope this book helps you create more space within yourself to embrace all of your complexities—your tenderness and your fire, your hope and your grief, your loudness and your softness, your strengths and your insecurities. You get to be fully human, fully worthy, fully free outside of the white gaze. Each time we come home to our identity beyond survival, it is a taste of freedom. May the taste of freedom linger on our tongues, reminding us what it is we are actually fighting for.

A Collective Approach to Wholeness Work

A popular quote, which is frequently cited as an African proverb, says, “If you want to go fast, go alone; if you want to go far, go together.” Here in the United States, we live in a go-fast-alone society. And even though I grew up in a collectivist culture that emphasized the go-together lifestyle, my natural tendency is to go fast alone. I’d much rather do something myself than try to figure out the expectations of a whole group of people. The me-centric individualism that is prevalent in the United States makes it easy to believe that an individual’s wellness, or lack thereof, is made possible strictly by each person’s independent effort. The pick-yourself-up-by-the-bootstraps mentality is a perfect example of this way of thinking, placing both glory and shame on the individual for what they achieve or fail to achieve while ignoring the systems set up for the benefit of only a few.

What we know to be true, however, is that our wellness and liberation do not exist separate from the collective. It is important to be clear, though, about what the word wellness means here. Wellness is a state of balance that comes from having our personal, relational, and collective needs met. Because wellness includes the personal, relational, and collective, there can be no wellness without justice. If the systems that govern our communities are structured in a way that ignores or even exacerbates our needs, we cannot be truly well. Those who have the power to protect themselves from systemic harm tend to define wellness simply as “love and light” or “choosing positivity and transcending pain.” But how can those who are consistently harmed by these systems ever be well by that definition?

Wellness work is not just the navel-gazing, self-care trend of long baths, face masks, and yoga studio memberships that’s been popularized by social media. This insular focus excludes the fact that wellness is our collective responsibility. Wellness and justice work must go hand-in-hand if we are truly to create a more equitable world.

In my post-master’s marriage and family therapy program, we talked often about what wellness and healing look like for individuals in the context of the systems in which they exist. For example, someone might come to therapy seeking support for their experience of anxiety. Looking through a purely individualistic lens, the focus of therapy would be to teach the client techniques to soothe or overcome their anxiety. The client might be encouraged to move their body or practice mindful breathing or make lists that help them focus only on what they can control.

If we looked at this same client through a systemic lens, we would become more curious about their identities and how those identities have impacted their history and current lived experience. What is their family system like? Do they feel supported and safe in their everyday life? Are they financially stable? Do they hold a marginalized identity, and if so, how have they experienced harm as a result? Do they have relationships in which they can fully be themselves without fear of harm or retribution?

Let’s say the client mentioned above is experiencing anxiety because they are highly qualified but keep being rejected from jobs due to the color of their skin. This leaves them vulnerable to the threat of eviction in the near future. Maybe they also take care of their aging parents financially, and without a steady, well-paying job, their family members will suffer too. While a reminder to move their body and deepen their breath is helpful, it doesn’t address the systemic harm at the root of this client’s anxiety. Supporting this person’s well-being includes not just individual soothing practices but also helping them find resources for the very real threat to their safety. Supporting them might also include holding a safe space for them to name and unlearn the racial gaslighting that often occurs in situations like these, where people of color are held individually responsible for the failings of an entire system.

The work of healing and coming home to our truest selves is deeply personal, but it cannot be extricated from our collective healing. The pursuit of our own healing and freedom has the power to transform our communities and the world. The freer we become on an individual, cellular level, the more freedom we bring to our relationships, our families, our neighborhoods, our communities. In relational community we learn what it is to love and be loved, to hold and be held, to see and be seen. A person who is living from a place of greater freedom has access to more choice—the choice to opt out and not collude with systems that oppress them or to reenact tha...