eBook - ePub

Available until 23 Dec |Learn more

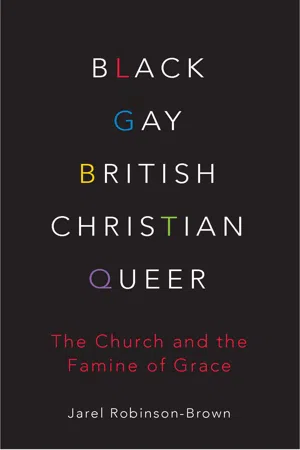

Black, Gay, British, Christian, Queer

The Church and the Famine of Grace

This book is available to read until 23rd December, 2025

- 144 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Available until 23 Dec |Learn more

About this book

If the church is ever tempted to think that it has its theology of grace sorted, it need only look at its reception of queer black bodies and it will see a very different story.In this honest, timely and provocative book, Jarel Robinson-Brown argues that there is deeper work to be done if the body of Christ is going to fully accept the bodies of those who are black and gay.A vital call to the Church and the world that Black, Queer, Christian lives matter, this book seeks to remind the Church of those who find themselves beyond its fellowship yet who directly suffer from the perpetual ecclesial terrorism of the Christian community through its speech and its silence.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Black, Gay, British, Christian, Queer by Jarel Robinson-Brown in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Sexuality & Gender in Religion. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1. ‘This is our story, This is our song!’

Amazing grace! how sweet the sound,

That saved a wretch; like me!

I once was lost, but now am found,

Was blind, but now I see.

’Twas grace that taught my heart to fear,

And grace my fears relieved;

How precious did that grace appear

The hour I first believed!

I think it is fair to say that when people think of grace – particularly when Black folk think of grace – the song that comes to mind is the hymn that calls it ‘amazing’, by John Newton. Written in 1772, ‘Amazing Grace’ has rooted itself in the minds and hearts of Black folk – you can hear it sung by Aretha Franklin, Diana Ross, Jessye Norman, Jennifer Hudson and even Barack Obama! As a song, it communicates something of God and something of our experience of God in this world in a way that somehow manages simultaneously to evoke both a feeling of connected spirituality in Black people and a sense of collective pride and unity. What it evokes in us, I suspect, is a deep feeling of gratitude and praise to our Ancient God who has carried us over and seen us through, guided and guarded us, and brought us to where we are now even with our manifold bruises. Yet ‘Amazing Grace’ is also a hymn full of paradox; the dissonance being that we are, as Black people, those who have not always been protected by God from the violence of White Supremacy, of capitalism and of Christianity. We sing full of faith of the goodness of God, even as those who know what God’s apparent abandonment looks and feels like. Both in our enslavement and throughout the Civil Rights Movement to the present day, Black faith, faith that is born in the furnace of our lives, has continued singing of the goodness and grace of God in the face of so much that speaks of God’s absence, betrayal and even death.

We who sing of amazing grace, despite what the world has done to us, carry an amazing faith, rooted in nothing but the promises of God whose promises are steadfast and sure. So rarely do we really interrogate the roots or history behind what we sing or even read in Church sometimes that we can find words take root in us whose origins we know nothing of. It is always a surprise to many, then, when they learn that this hymn was written by a White, Anglican priest who was born in East London and worked on three slave ships – Brownlow, Duke of Argyle and the African over a period of about five years. Eventually, 34 years after retiring from the slave trade, Newton became an abolitionist having penned the hymn ‘Amazing Grace’ a few years prior. It is a bittersweet thing that a hymn so loved by so many Black folk, so emblematic of our spirituality and our community, is one written by a man who participated in our dehumanization and enslavement. Now, when I sing this hymn, I can’t help but think of Newton and whatever was going on in his mind and heart when he wrote the hymn. But I also find my mind thinking of all those of our African ancestors who suffered under him and his colleagues and whose names and stories we will never fully know because they lie at the bottom of the ocean, or are drowned by unrecorded history. For all my love of the hymn and what it evokes in me, nowadays I refuse to sing the words ‘that saved a wretch like me’.

wretch (noun)

1: a miserable person: one who is profoundly unhappy or in great misfortune

2: a base, despicable, or vile person1

The contradiction that exists here is striking. We Black folk are invited to sing of the amazing grace that we have received and yet also made to see ourselves as a wretch that has been saved by that grace. I have no idea what Newton thought we would feel singing this, but I reserve the right in this day to ensure that I do with White people’s work as I wish, and sing, read and pray those things that I find edifying and spiritually helpful. This disconnect, of course, goes beyond Newton’s words – it affects every aspect of life in the Christian community because there are some who have always been made to feel like wretches in the house of God, and some who have not. As a younger person this contradiction between what the Church said and what we sung registered for me in a number of ways, and what it told us was true. I had back then, in my youth, no articulate theological grammar with which to coherently address why I found it contradictory to be both the recipient of amazing grace and a ‘wretch’ whom God had saved – this wretchedness could easily be located in my Blackness and my Queerness in this world and Church where both are regularly despised, discussed and contested. Although I was entirely aware of the fact that not all people were ‘good’ and ‘holy’, it was a long time before I knew for myself what sin was, and occasionally sat in church feeling I had to dig deep to find things of which to repent in the long silence our minister left during prayers of confession. I could sit and ponder – what was it, really, about my young Black Queer life that made me a ‘wretch’ in need of grace? And now, although this is no longer the case, I still have moments when it is easy to fall into the trappings of guilt, where the language of the Church – of the ‘wretch’, the ‘offender’, the ‘unrepentant sinner’ – wrap themselves around my humanity like a blanket of broken glass and hold me hostage before the liberative and redeeming God. Guilt, I have come to learn, is a fetish, and it is one that early on in our Christian formation we are made to feed on and grow accustomed to – although we sing of grace we so often feel it offered to us by the Church piecemeal and with terms and conditions that human beings have laid down in an attempt to exert power and control, and this leads to the ultimate cognitive and spiritual distortion. The Church early on in a Christian’s development places itself in position as a Dom Top, and everyone, particularly those marginalized, are supposed to Bottom at any given time, submissively and without complaint. This spiritual distortion, a distortion in our relationship both to God and the Church, leaves us querying the fact that for all the evidence to the contrary in our experience of God, we are perhaps divorced from God and more frighteningly from one another. It is this sense that grace must be earned that pushes us Black LGBTQ+ folk to hide all the non-heteronormative parts of ourselves in an effort to win God’s love, the Church’s welcome and the pastor’s favour. The same pastors who, even though they know and have preached on St Paul’s words about us human beings who ‘have this treasure in clay jars’ (2 Corinthians 4.7), spend all their time guiding us to focus miserably on the clay-ness of ourselves and negating all the treasure. It is through them that we come to learn the very opposite of grace, through those individuals and communities who fail to accept, embrace and love us as God loves us, that we believe the lies the world tells us, and that we eventually swallow and feed on as truth. That to be queer is to give up our right to Blackness, that to be Queer is to turn our back on God, that to be queer is to choose the way of sin, the world and the devil. We know how it goes, and we know the story so well, because it is our story, and our song. It is because of this primal disconnect between our spirituality and our real lives that we begin so early on to compartmentalize a God who exists to live with us in every moment, but who we are led to believe denies us the deepest joy. It is this that forces us to leave God (at least in our minds) at the door of our bedrooms, because we cannot believe that he can be with us in moments of sexual intimacy and bodily embrace, toe-curling ecstasy and spine-tingling climax. But what happens to our spirituality, what happens to the souls of Black Queer LGBT+ folk when we believe God turns God’s face away at the moments when we feel most human? What I came to discover about the Church over the years, James Baldwin the African-American playwright, essayist, activist and novelist came to discover years earlier about America:

It comes as a great shock around the age of five or six or seven to discover that the flag to which you have pledged allegiance, along with everybody else, has not pledged allegiance to you. It comes as a great shock to discover that Gary Cooper killing off the Indians, when you were rooting for Gary Cooper, that the Indians were you. It comes as a great shock to discover that the country which is your birthplace, and to which you owe your life and your identity, has not in its whole system of reality evolved any place for you!2

One of my earliest memories is of Sundays and involves the Church. For so many Black Queer and trans folk, the Christian community is no stranger – we know it as intimately as we know the contours and limits of our desire. We remember the early Sunday mornings, the unchanging lateness, the watered-down squash, stale custard creams, and tea that was more milk and hot water than actual tea …! We remember the Church aunties and uncles, the gossip and the love, the running around with our friends and being held behind while our parents caught up on a week’s worth of news with their favourite brothers and sisters in the Lord. In its own special way, the joint component of all those things rendered the Church a kind of second home. It is within the walls of these buildings and in the presence of these people that we shed tears, call upon God, get slain in the Spirit, receive healing, hear God’s voice and tell the Lord the burdens of our hearts. We, as Black folk, know that our churches are really trauma rooms, accident and emergency units, psychiatric wards, maternity rooms, counselling spaces – that, in fact, people encounter all kinds of healing and bring all kinds of burdens to God in these spaces. We as Black folk have had an intimate relationship with the pain and suffering we come to know so well in the Jesus nailed to the cross. It is in these spaces and within this Church family that our elders found the balm that touched so profoundly the hurting and tender parts of their lives and memories. I, perhaps like you, have been loved and hated by the Church, healed and hurt by the Church, encouraged and confused by the Church, enchanted and disillusioned by the Church. This makes it both a hard and a holy thing, to tell the Church how I really feel about it – in part, because the experience and the memories are neither wholly bad nor wholly good.

When Baldwin says that ‘writers are obliged, at some point, to realize that they are involved in a language which they must change’,3 I realize that so much of my language has been shaped by the Christian vocabulary, that it has both given voice to my feelings and silence to my fears. When I think back now, with the lenses of honesty and maturity, I value so much of what the good parts of church life taught me. Sundays were the day when families gathered together. So many Sundays passed that involved me standing in the kitchen with a giant wooden-handled fork that looked as though it had made its way over from St Thomas, Jamaica, in someone’s luggage. There I stood, turning over frying plantain as I negotiated jumping splashes of hot oil while my Nan was sitting in her bedroom peeling potatoes on her lap, watching the EastEnders omnibus, and my mother was listening to one of the many Jamaican artists that featured in my childhood. Essentially that meant either Capleton, Beres Hammond, Gregory Isaacs or Freddie McGregor were the background noise to my culinary efforts, if Peggy Mitchell wasn’t kicking people out of her pub. Somewhere between Capleton’s homophobic lyrics in ‘Slew Dem’ and Freddy McGregor’s not wanting to be lonely was a little British-born Jamaican boy who loved Jesus but also knew he liked other boys, and later learnt he could love them too. I was, as Beres Hammond sang, ‘Tempted to touch’, but I had not yet known what another boy’s body would do to mine, or what mine might do in another boy’s embrace. That came later, and was as terrifying and magical as I had imagined.

After I’d come to terms with the fact that I would never get to lips Syed Masood and confirmed that Ben Mitchell and I had a lot in common, it wasn’t long before I came to realize that both Capleton and White Christianity were not for me, in the sense that neither of them had in mind a free version of me as the Black Queer Christian that I am. At times it feels as though, if the universe had had its way, I would have certainly given up on being either openly gay or openly Christian, but I guess the universe doesn’t always get its own way. When folk in church would ask me if I had a girlfriend, and old Jamaican men would encourage me during a Nine-Nights to dagger a chick next time I was raving, the paradox in my life became clearer and clearer. I, like everyone who is honest, was many things. I knew I wanted to be a priest and that rather than this being a grandiose imagining it was genuinely from God. I also knew that at that time my sexuality was anything but straightforward – was I ‘into’ men or ‘into’ women, and what the hell did any of that mean anyway? Could I be ‘into’ both? Could I have a same-sex partner and be ordained? Or did I have to forfeit Love in search of love. Was it possible to be gay and Jamaican? Christian and gay? Black, gay, Christian, Jamaican and proud of all four? Just as James Baldwin discovered about the flag of America and the United States, I was soon to discover that on the whole not just the Church but more specifically White Christianity, heteronormative Jamaican culture and even my own family had ‘not in its whole system of reality evolved a plac...

Table of contents

- Copyright information

- Contents

- Dedication

- Epigraph

- Foreword

- Preface and Acknowledgements

- Poem

- Introduction

- 1. ‘This is our story, This is our song!’

- 2. Grace Enough for Thousands?

- Poem

- 3. Grace Crucified

- Poem

- 4. Grace and Queer Black Bodies

- Poem

- 5. ‘I’m tired of this Church!’

- Epilogue

- Appendix. Sustaining Grace: Seated at the Right Hand of Zaddy