![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Archaeological Approaches to Landscape, Identity and Material Culture

Introduction

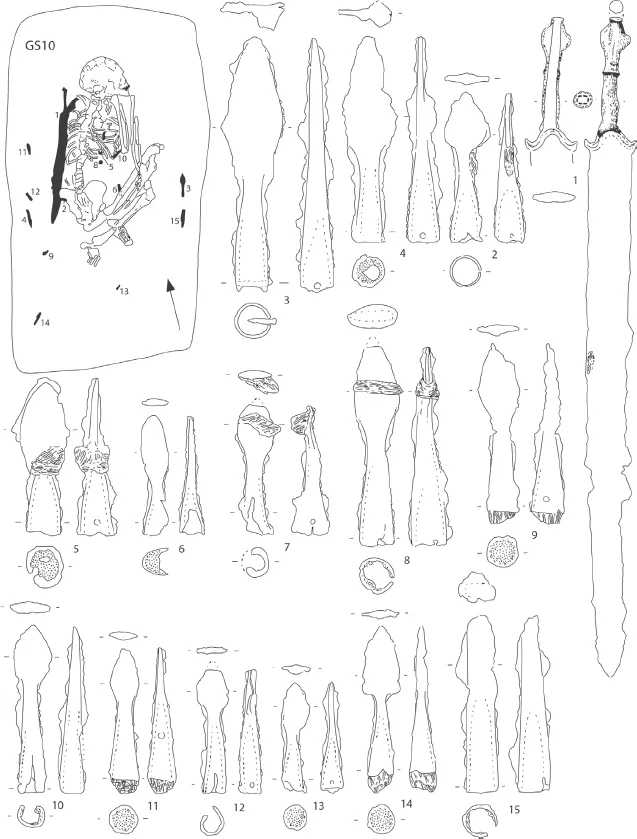

September 1985. Sifting through the fill of a square barrow burial, in a shallow chalk valley near Garton Station, the digger’s trowel hit something hard and metallic. Carefully easing away the silt, flakes of decayed iron fell away from the stump of an object. It was the circular end of a spearhead, embedded tip-down in the grave fill. Working carefully but eagerly, the rest of the grave was emptied. In total, 14 spearheads were recovered, perched in the soil at many different levels (GS10, Stead 1991, 224). Traces of mineralised wood suggested the shafts of the spears were intact when they were thrown into the fill of the grave. Near the base of the pit, six of these were embedded in the tightly crouched body of a young man, who was aged between 25–35 years old when he died. The spears seem to have splintered and pierced through a hide-covered wooden shield which had been laid over the rib-cage, and an iron sword lay just behind his back. Although there were no obvious signs of injury on the skeleton, deep flesh wounds, strangling or poisoning would have left no mark, nor would many common but dangerous infections.

Piecing together the evidence, the director of the excavations, Ian Stead, realised that this burial had been the focus of an elaborate funerary ritual. The grave had been cut into the bed of the local stream – the Gypsey Race (pronounced with a hard ‘g’) – probably when the waters had dried up, or were running shallow (Figure 1.1). Perhaps it had been a long, hot summer, when either tempers had flared or disease had run rife through the local community. Whatever the cause of death, the loss of this man in the prime of his life, must have been deeply felt. By this age, he would have become a respected father, farmer, hunter or fighter: skilled at wielding a spear. From the trajectory of the weapons, we can guess that at least four individuals took turns to cast their weapons into his body, as the grave was rapidly backfilled. Why ‘kill’ someone who was already dead? Was this a mark of honour or a gesture of fear? Whatever the motivation, the shafts of their spears would have stuck out of the resulting barrow mound, like bristles or spines. Taking years to decay, they would have become a long-lasting and dramatic reminder of the events that had taken place there.

This individual was not alone: there are four further burials interred in this manner in the cemetery, adjacent to each other (GS4, GS5, GS7 and GS10, Stead 1991, 22). They may have died together, or months or years apart: we have no way of knowing. What binds them together is the fact that they are all adult males, ranging from their late teens to early 30s. They were all associated with ‘martial’ objects: spears, bone points, shields and a sword. And it is clear that the place of burial – in the very bed of the local chalk stream, running along the base of the valley – was also significant.

FIGURE 1.1. Burial of GS10. Based on Stead 1991, 223, fig. 124.

The three themes highlighted by this burial – the place where they were buried, the identity of the dead and the objects they were buried with – form the core of this book. ‘A forged glamour’ is an archaeological study of the lives and deaths of the Iron Age inhabitants of the Yorkshire Wolds, who are renowned for their square barrow cemeteries, and the rare but impressive chariot burials which are occasionally found within them. It seeks to interpret the drama of these funerary rites within the context of everyday life: the more mundane landscape of settlements, stock-raising and craftwork, through which their concerns, fears and ambitions took shape. Each chapter of the book will focus on a different theme or area of those lives. Weaving between these chapters will be a study of the relationship between the living and the dead.

We only come to know these people through the traces they left behind: the material culture of banks and ditches, roundhouses and barrows, human and animal remains, and artefacts, which they made and deposited in this landscape. Whilst the classical authors refer broadly to habits of the pre-Romanised Britons, we have no account of East Yorkshire until names of places and tribes are listed by Ptolemy in the 2nd century AD. This first chapter is thus a study of how we know what we know: a history of research in the area, from the days of the earliest antiquarians to the modern era of developer-funded contract archaeology. Throughout this first section, I will consider how the three key themes of the book – landscape, identity and material culture – were viewed by each generation of archaeologists, evaluating how and why their ideas changed, and outlining the challenges we still face. First, it is vital to appreciate the landscape which both shaped these later prehistoric communities and was simultaneously transformed by them.

The Yorkshire Wolds

Introducing the landscape

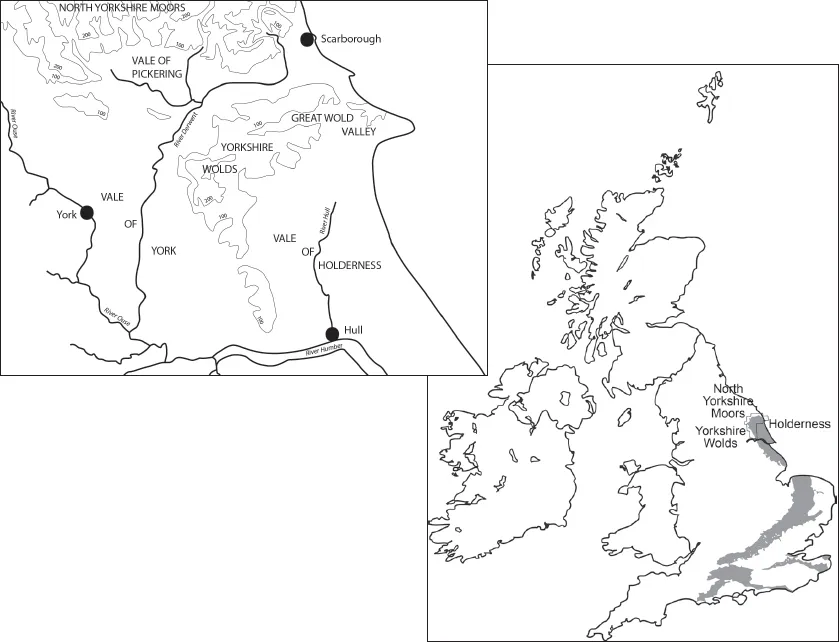

The Yorkshire Wolds form a crescentic arc of chalk hills, rising at Hessle on the northern shore of the river Humber, and turning gently eastwards, to outcrop at Flamborough Head, on the North Sea coast (Kent 1980). They are located within the counties of both East and North Yorkshire (Figure 1.2). To the west of the Wolds lies the relatively flat Vale of York, and – close to the foot of the Wolds itself – the Foulness Valley: dissected by the headwaters of the Humber and its tributaries. To the north, the Vale of Pickering stretches out towards the Howardian Hills and the North Yorkshire Moors, watered by the river Derwent. Finally, to the east is the gently undulating land around the River Hull, sinking into the low-lying Vale of Holderness. The rapidly eroding coastline fringes the region to the east.

From a distance, the Wolds form an impressive block of land, rising out of the surrounding vales, but their unitary appearance is deceptive. The scarp edge of the Wolds, especially in the north-west, consists of extensive ‘swells and plains’ (Leatham 1794, cited in Woodward 1985, 34): broad, open Wold ‘tops’ dissected by sharp, ‘v’ shape dry valleys. Many of these dales (as they are known locally) were formed when faults in the chalk were worn open by glacial activity, which often left deposits of moraine (crushed chalk and worn flint gravels) in their bases. These gravels are often overlain by several metres of hillwash (‘colluvium’, Hotson 1985): the result of the natural erosion of the land surface, exacerbated by centuries of cultivation (Foster 1987; Evans 1992) and the aerial denudation of soils (Reid 1885; Furness and King 1978). The high, sharp sides of these valleys form long, sinuous corridors, with frequent side dales and steep valley heads. In places, they feel almost claustrophobic. In contrast, the exposed Wold tops in between these dales are open to the wide canopy of the sky. The brilliance of the stars up here on a clear, autumn night is awe-inspiring.

FIGURE 1.2. The landscape of the Yorkshire Wolds and surrounding region.

As you move down from these highest parts of the Wolds onto the eastern dipslope, the topography becomes less severe. The Great Wolds Valley, which dissects the eastern arm of the Wolds, has a broader base, rising to slighter hills on each side. Further south, these are called ‘slacks’, as at Wetwang and Garton. Gradually, they give way to more undulating land, as the chalk of the Wolds meets the Holderness Plain. Here, glacially deposited bars of tills and fluvio-glacial gravels (Reid 1885; Van der Noort and Ellis 1995), are punctured by kettle holes: formed as these capping deposits collapsed into hollows left by melting ice blocks.

Today, after centuries of drainage, canalisation, reclamation and land improvement, it is hard to appreciate what the lower-lying later prehistoric landscape around the Wolds would have looked like. In Holderness in particular, it would certainly have been wetter: a mosaic of richly-vegetated marsh and submerged forests, rising peat deposits, small spring-fed streams, seasonal floodplains and more permanent meres, as at Hornsea. To traverse certain areas of this landscape would have required intimate local knowledge of safe routes across slightly higher ground, as well as the use of water transport, such as the Brigg rafts and Hasholme boat (Millett and MacGrail 1987; MacGrail 1990; Wright and Churchill 1965; Wright 1990). By the early Iron Age, some clearance of the Holderness landscape is suggested (Dinnin in Van der Noort and Ellis 1995) although grazing and cultivation may have been limited to better drained areas of sand and gravel (Didsbury 1990).

It is unlikely that later prehistoric communities were restricted to one area of the landscape. Whilst the Wolds may have had a distinct identity arising from its bedrock, soils and topography, as well as its commanding views, communities from it moved down into the surrounding Vales, to meet with others, exchange resources and news, and make use of seasonally available foodstuffs, pasturage or water (Fenton Thomas 1999). Equally, groups from off the Wolds made journeys up into the hills, for similar reasons. The evidence for this will be discussed later in the book, but it is important not to see the Wolds as an isolated region, but rather a distinct yet internally varied zone, set within a diverse broader landscape utilised by many communities.

History of archaeological research

The Yorkshire Wolds have been well-investigated by archaeologists over the nineteenth to twenty-first centuries. There are several reasons for this. A highly visible set of monuments (long, round and square barrows, a massive standing stone at Rudston and kilometres of linear earthworks) attracted the interest of a series of antiquarians. Initially they were collectors, such as Thomas Kendall of Pickering, but others, such as Jas. Silburn and Barnard Clarkson actively investigated these ancient monuments (Marsden 1999). Some were of independent financial means (such as Canon Greenwell, who also worked extensively from North Yorkshire to Northumberland, 1877). Others (such as John and Robert Mortimer) were funded in part through the patronage and encouragement of local landowners (the Sykes of Sledmere, in particular), as well as the profits of their business activities (Giles 2006). Their research was facilitated through a vigorous, and often aggressive agricultural regime, which saw the large-scale ploughing-up of earlier pastoral regions known as ‘sheepwalks’, during a major period of land improvement (Harris 1996). Vast quantities of surface finds, particularly lithics, were recovered by agricultural labourers, and sold for financial reward (Sheppard 1929, iii). Other activities resulted in the accidental discovery of remains, such as the creation of the Malton to Driffield railway (Mortimer 1905a, 194), quarrying for chalk or clay digging (ibid., 238) and road-mending (Mortimer 1889). Sometimes, farmers or labourers reported the finds that had been disturbed as they cut into or even levelled ancient barrows (Mortimer 1905a, 113, 359). Both Greenwell and Mortimer solicited news of such finds, rushing to record the discovery and collect whatever artefacts remained (Greenwell 1906; Mortimer 1869). However, these barrow-opening activities sometimes had unintended consequences, as reported in the Driffield Times and General Advertiser for Saturday 6 December 1862 on page 3. A labourer who had previously assisted an unnamed antiquarian took it upon himself to open another barrow ‘actuated by a desire of profit’, but rather than uncovering valuable artefacts to sell he made an ‘unfortunate sepulchral discovery’, much to the horror of the landowner as well as the editor of this local newspaper!

The archaeology of this region became much more widely known and appreciated through an assiduous programme of public speaking at local institutions and regional societies by Greenwell and Mortimer, as well as another interested amateur: the local vicar of Wetwang Slack, E. Maule Cole. The subsequent publication of these lectures in the associated proceedings helped disseminate their discoveries and ideas, as did the longer articles and major monographs by both Greenwell (1877) and Mortimer (1905a). John Mortimer’s Driffield Museum of Antiquities and Geological Specimens also made his collection available to fellow scholars, even if access to the general public was more restricted (Giles 2006, 290). By bequeathing his collection to the British Museum, Greenwell’s material gained a much wider audience upon his death. In contrast, the purchase of Mortimer’s collection by the Hull and East Riding Museum in 1913 (engineered by the curator Thomas Sheppard) respected the wishes of its creator by ensuring it remained in the district in which it had been collected (Harrison 2001). By the early twentieth century, it was evident that the Iron Age archaeology of East Yorkshire had a considerable role to play in narratives of both regional and national identity (Giles 2006).

By the middle of the twentieth century, archaeological techniques – particularly the use of aerial photography – were transforming knowledge of the underlying prehistoric landscape. The light chalk soils which cover the Yorkshire Wolds, are easily worked, and the post-war increase in arable production, enabled by the use of new machinery and artificial fertilizers, made the area particularly profitable for recording soil and crop marks (Stoertz 1997, 1). In addition, large tracts of grazed pasture still contained upstanding earthworks, and dry summers helped reveal further sites through ploughed-out parch marks (ibid.). From the 1950s–1990s, the Royal Commission on the Historical Monuments of England (RCHME), took thousands of aerial photographs, which resulted in another seminal archaeological publication: the comprehensive mapping programme undertaken by Cathy Stoertz, and published in 1997. Alongside the work of other local flyers, these images began to stimulate further programmes of archaeological research. These were undertaken by individual local researchers such as Terry Manby and Tony Pacitto, amateur rescue archaeologists such as the Granthams of Driffield, as well as institutions such as the British Museum, whose impressive programme of research was directed by Ian Stead. In addition, the large-scale gravel quarrying activities at Garton and Wetwang Slack led to a co-ordinated programme of excavation, initiated by T. C. M. Brewster and carried forward by John Dent. Other research programmes have included the work of Dominic Powesland, on the edge of the Wolds at Heslerton; survey and excavation in the Foulney Valley by Peter Halkon and Martin Millet; long-term excavation by Rod Mackey at the villa site of Welton Wold; the work of the East Riding Archaeology Society; and research by the Wharram Landscape Project, directed by Colin Hayfield. University-driven research by departments of archaeology at Sheffield, York, Hull and Manchester, have also enriched knowledge of the region. More recently, developer-funded work on both housing and pipeline projects have yielded fascinating results both on and off the Wolds, undertaken by various units, including the locally based Humber Field Archaeology, Northern Archaeological Associates and On-Site Archaeology.

The result of all of this research is a vast body of archaeological data relating to the Iron Age, investigated to different standards and under different agendas. Caution is needed when comparing the records of antiquarians with contemporary archaeological investigation carried out under the guidance of current planning guidance (PPG16, PPS5). Even then, many of the more recent excavations – particularly those at Wetwang Slack and Wetwang Village – have yet to be published, or exist merely as a microfiche report (e.g. Brewster 1980). However, as a result of this work by many individuals, the general character of the Iron Age archaeology can still be confidently outlined.

The character of the Iron Age landscape

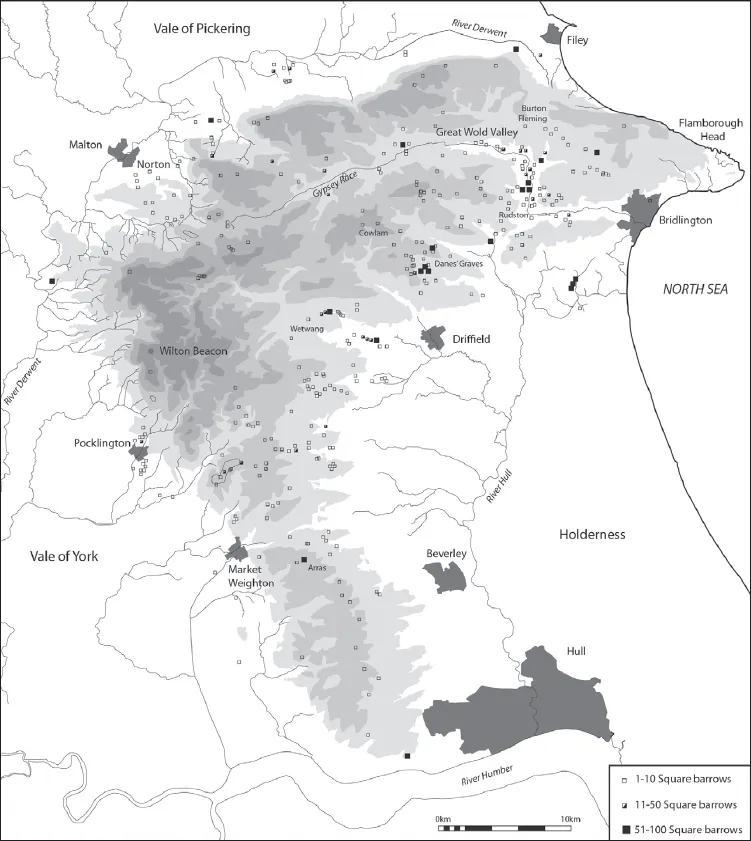

It is the funerary evidence which dominates accounts of the region. From around the fourth century BC to the mid-first century BC, inhumations became increasingly numerous. Small groups of square barrows (such as Cowlam) or isolated graves, contrast with larger cemeteries at Arras, Danes Graves, Burton Fleming, Rudston and Wetwang/Garton Slack. The largest cemeteries are usually found in the base of valleys at the edge of the Wolds dipslope, or clustered along the Great Wolds Valley (Figure 1.3). However, smaller cemeteries are also found in Holderness and the most northerly barrow cemetery has been recorded at Slingsby in North Yorkshire, with outlying chariot burials discovered on the North Yorks Moors and in West Yorkshire.

Some burials were deposited on the ground surface but later inhumations were generally interred in grave pits (Stead 1991, 228). They were commonly surrounded by a square enclosure ditch, with the up-cast spoil used to create a small covering mound or barrow. However, by the 1990s, it was recognised that some graves had a circular enclosure ditch, whilst others had none (Stead 1991, 7). The body was generally crouched or contracted, with the head commonly orientated towards the north end of the grave, facing east (ibid.). Grave goods were scarce but included brooches, items of jewellery, and small earthern-ware jars which sometimes contained a joint of mutton. Rarer artefacts included tools and weapons (Stead 1979). However, the most impressive burials within these cemeteries were the ‘chariot’ or ‘cart’ burials: inhumations surrounded by the remains of two-wheeled vehicles with a central pole shaft, originally pulled by a pair of ponies. The trappings of these chariots were frequently arranged around the body: horse-gear and decorative ornaments, as well as personal items such as swords and mirrors. From the antiquarian writers onwards, these chariot burials have been seen as the graves of the local chiefly Celtic elite. Their similarities with burials on the Continent have led to the assumption that the burial rite itself is the result of a migration from Iron Age Europe: an interpretation which will be extensively discussed throughout this book.

FIGURE 1.3. Square barrow cemetery distributions. 1. Wetwang Slack; 2. Garton Slack; 3. Garton Station; 4. Kirkburn; 5. Eastburn; 6. Cowlam; 7. Danes Graves; 8. Burton Fleming (BF1-22); 9. Rudston (190–208); 10 Rudston (Makeshift, R1-189); Burton Fleming (Bell Slack BF23-64); 12. Grindale (Huntlow). Based on Stoertz 1997, 34, fig. 15.

Alongside this rich material is the scanter evidence for settlement: roundhouses, four and six-post structures, pits, gullies, enclosure ditches, track-ways and fence-lines, as revealed in the extensive open area excavation along the Wetwang and Garton Slack valleys. Smaller windows into settlement activity have been provided at villa sites such as Rudston (Stead 1980) and other late Iron Age–early Roman farmsteads, where an early phase of occupation frequently underlies later activity. In contrast, ‘hillforts’ are rare and diverse in form: they largely appear to be a late Bronze Age/earliest Iron Age phenomena and as the scope of this book focuses on the middle–late Iron Age, they are not discussed in detail here (see instead Giles 2007c). Evidence for agricultural activity is scarce: there are no well-preserved field systems, so environmental evidence (of both flora and fauna) is particularly valuable (Wagner 1992). However, the landscape is framed by a series of impressive linear earthworks, which seem to date to the late Bronze Age but continue to be modified throughout the first millennium BC (Giles 2007c) and these can be used to gain a (speculative) insight into patterns of landscape use.

Summary

So far, this chapter has introduced the Iron Age landscape of the Yorkshire Wolds, and it has briefly reviewed the history of investigation in the region. Returning to the discovery at the beginning of the chapter, it is now time to delve a little deeper into the work and ideas of these key researchers, to explore the ways in which this material has been used by them to explore one of the three key concepts of this book: identity. Since its formal origins as a social science, archaeology has prided itself on being able to contribute to understandings of humanity through a long-term perspective on the past. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the discipline made claims about the nature of different human races, the spread of particular cultures, and the degree of civilisation they represented, which unfortunately helped underpin and justify colonial and nationalist programmes of expansion, invasion and exploitation (Jones 1997). By the mid-20th century, these debates had turned to the pressing issue of the indigenous or invasionary origin of Britain’s inhabitants, when again the East Yorkshire material was used to exemplify...