- 400 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

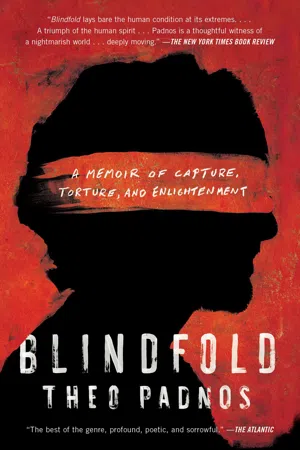

An award-winning journalist’s extraordinary account of being kidnapped and tortured in Syria by al Qaeda for two years—a revelatory memoir about war, human nature, and endurance that’s “the best of the genre, profound, poetic, and sorrowful” (The Atlantic).

In 2012, American journalist Theo Padnos, fluent in Arabic, Russian, German, and French, traveled to a Turkish border town to write and report on the Syrian civil war. One afternoon in October, while walking through an olive grove, he met three young Syrians—who turned out to be al Qaeda operatives—and they captured him and kept him prisoner for nearly two years. On his first day, in the first of many prisons, Padnos was given a blindfold—a grime-stained scrap of fabric—that was his only possession throughout his horrific ordeal.

Now, Padnos recounts his time in captivity in Syria, where he was frequently tortured at the hands of the al Qaeda affiliate, Jebhat al Nusra. We learn not only about Padnos’s harrowing experience, but we also get a firsthand account of life in a Syrian village, the nature of Islamic prisons, how captors interrogate someone suspected of being CIA, the ways that Islamic fighters shift identities and drift back and forth through the veil of Western civilization, and much more.

No other journalist has lived among terrorists for as long as Theo has—and survived. As a resident of thirteen separate prisons in every part of rebel-occupied Syria, Theo witnessed a society adrift amid a steady stream of bombings, executions, torture, prayer, fasting, and exhibitions, all staged by the terrorists. Living within this tide of violence changed not only his personal identity but also profoundly altered his understanding of how to live.

Offering fascinating, unprecedented insight into the state of Syria today, Blindfold is “a triumph of the human spirit” (The New York Times Book Review)—combining the emotional power of a captive’s memoir with a journalist’s account of a culture and a nation in conflict that is as urgent and important as ever.

In 2012, American journalist Theo Padnos, fluent in Arabic, Russian, German, and French, traveled to a Turkish border town to write and report on the Syrian civil war. One afternoon in October, while walking through an olive grove, he met three young Syrians—who turned out to be al Qaeda operatives—and they captured him and kept him prisoner for nearly two years. On his first day, in the first of many prisons, Padnos was given a blindfold—a grime-stained scrap of fabric—that was his only possession throughout his horrific ordeal.

Now, Padnos recounts his time in captivity in Syria, where he was frequently tortured at the hands of the al Qaeda affiliate, Jebhat al Nusra. We learn not only about Padnos’s harrowing experience, but we also get a firsthand account of life in a Syrian village, the nature of Islamic prisons, how captors interrogate someone suspected of being CIA, the ways that Islamic fighters shift identities and drift back and forth through the veil of Western civilization, and much more.

No other journalist has lived among terrorists for as long as Theo has—and survived. As a resident of thirteen separate prisons in every part of rebel-occupied Syria, Theo witnessed a society adrift amid a steady stream of bombings, executions, torture, prayer, fasting, and exhibitions, all staged by the terrorists. Living within this tide of violence changed not only his personal identity but also profoundly altered his understanding of how to live.

Offering fascinating, unprecedented insight into the state of Syria today, Blindfold is “a triumph of the human spirit” (The New York Times Book Review)—combining the emotional power of a captive’s memoir with a journalist’s account of a culture and a nation in conflict that is as urgent and important as ever.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Blindfold by Theo Padnos in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Social Science Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1 MY PLAN

Antakya, Turkey, October 2012

My plan was to find the cheapest possible dive in Antakya, Turkey. I would sleep there, then make daytime excursions across the border, into Syria. Steering clear of the violence, since I was no combat reporter, I would discover quirky but telling stories about life in the shadow of the Syrian revolution. I would type these up, then dispatch them to editors in New York and London.

For a freelance reporter, the greatest certificate of success was a commission from the New Yorker or the Atlantic. Those magazines, I understood, paid reporters as much as $10,000 per article. Rolling Stone paid similar sums. During the previous years, I had sent out pitch letters to the editors of these magazines. I hadn’t gotten a flicker of interest from any of them. Mostly, the editors didn’t reply at all. What was up with those people? Maybe they wanted baksheesh. Maybe they awarded contracts only to their college roommates.

I was fine with this. I had options. A year earlier, I had written two essays about the troubles in Syria for the New Republic’s website. As I wrote, I was under the impression that a chaotic but beautiful upending of the social order was sweeping through the country. I knew that a few Islamists, probably off in the hinterland, had made their presence known and that the deep cause beneath the violence was the people’s wish to be rid of their dangerous-because-very-stupid dictator, Bashar al-Assad. And thus to be free.

In July of 2012, in Vermont, I watched via the internet as crowds ten thousand people strong danced in the central square in Hama, the site of an earlier revolt (1982) against an earlier President Assad (Hafez, the current president’s father). The crowds roared with naughty happiness as they sang to their president:

- Kiss my ass and let all those who bow before you kiss it, too. O, by god, no one gives a shit about you.

This looks like good fun, I thought. I knew that financing a reporting trip to Syria wasn’t going to be easy. The New Republic’s website had paid me $800 per article. I had to ask them to send the money to me in Damascus via Western Union. The Western Union agent in Damascus had taken about $80 off the top each time. An accountant would have added up the cost of the plane to Beirut, the collective taxi to Damascus, the visas, and the expenses on the ground in Syria. To an accountant, it would have seemed that each essay cost me about $800. I wasn’t interested in accounting.

I had loved writing those essays. I wrote them in the early, heady days of the Syrian revolution, in the summer of 2011. Those essays brought me into the living rooms of religious savants in Damascus. They encouraged me to learn the lyrics of the radio hits there and to interview the Damascene pop stars. The writing had directed me into bits of the Koran I had known nothing about. Composing those website essays had been like a miniature graduate school for me in which the cultural life of the capital was my professor. My fellow citizens were the students. When the articles appeared on the New Republic website, I felt I had captured a true, terrifying zeitgeist in the capital about which no one there could speak. When readers commented on my essays, I felt they were attesting to a talent in me—essay writing about Syria—I hadn’t dared to believe in myself.

Naturally, a problem cropped up. In the late summer of 2011, as the violence in the Damascus suburbs worsened, the Syrian government, fearing spies, revoked the visas of most of the Westerners living in Damascus. I had to go home to Vermont. And then the owners of the New Republic sold their magazine. The new editors did not reply to my emails.

Over the following months, I developed a new plan. I would send out letters to the world’s second-tier, lower-pay, low-prestige publications. Didn’t such magazines abound in the world? I didn’t know. I assumed they must. Meanwhile, there was news to report.

In October of 2012, the nation of Syria appeared to be wandering into a sea of blood. In many of the poorer urban districts, and in all of the rural ones, the government had collapsed. In some places, the government officials had defected to the rebel side. In other places, the police, the state security agents, and the military men had been driven away. Elsewhere, as more than a few YouTube videos attested, the representatives of the ancien régime had been lined up, made to kneel in the dirt, then shot through the back of the head.

“We are your men, O Bashar, and we drink blood!” So went the chants the pro-Assad militias made in the wake of their victories, recorded, then posted to the pro-government YouTube channels.

“To heaven! To heaven! To heaven we will go, martyred by the millions!” So went the chants the anti-Assad crowds made during their demonstrations.

In those days, my general feeling was that the revolutionaries were on the side of the angels. I felt that the Syrian Kurds, whose Iraqi brethren had learned to guide American smart bombs to their targets during the Iraq war, could work with Western air forces and democrats on the ground inside Syria to overthrow President Assad. After the air campaign, I thought, the time would come to storm the barricades. I assumed that the revolutionaries would find me charming. Seeing how admiringly I wrote of them and respecting the freedom of the press, they would, I thought, chauffer me from protest to internet café to village square. Because it would be hot and because the rebel brigades would be in possession of confiscated villas, the rebel commanders, I guessed, would allow me to write out my stories in the shade, by the side of the villa swimming pools.

The genius of my plan was that it required almost no money to launch. No money, in my opinion, would make the reporting better. My affection for Syria, my network of friends there, and my familiarity with the beautiful Arabic language—this, I told myself, was the start-up capital that counted. Penny-pinching would force me to sleep in mosques, to take the city bus, to hitchhike where locals hitchhiked, to eat in the houses of friends, and to learn the secrets of Middle Eastern travel austerity from the resident authorities: pilgrims, itinerant tradesmen, and students.

Most people in Syria are poor. Poverty, I told myself in Vermont, ought to be the sine qua non criterion by which editors judged the fitness of the reporter who wished to write about the Syrian people.

In the early summer of 2012, I nearly emptied my bank account—and so added to my eligibility as a reporter—by making a trip to Syria. A generous elderly, possibly out-of-the-loop consul in Houston gave me the visa through the mail. No editors in New York and none in London, it turned out, wished to publish the essays I proposed to them. That trip cost me $1,500. Later, in July, in Vermont, on a whim, I bought a Cannondale racing bike. That bill came to $1,800. Running low on cash, I sold a few things. I borrowed from my mother. At the end of the summer, I had enough cash for a new ticket to Turkey. In order to pay for expenses on the ground, I borrowed again from my mother.

I boarded the plane for Istanbul in early October. Assuming that in the fullness of time, when my reporting career was flourishing, I might hop over to the island of Cyprus for a few weeks of cycling, I brought the Cannondale. I spent my first night in Istanbul on the floor, in a room occupied by a friend I had made during my earlier, fruitless trip to Syria. I told this friend, Freddy, an asylum seeker from the Democratic Republic of the Congo, that I had some reporting work to undertake in Syria. Would he be willing to house my bike during the two weeks or so in which I would be away? Of course, he said.

Freddy, it turned out, objected to all ideas concerning Syria. “What do you want with those people?” he asked. As my host in Turkey, and an able Turkish speaker, he felt himself under an obligation to look out for me. During my twenty-four hours with him, I admitted to him that my American cell phone didn’t work in Turkey. It would have cost me $50 to unblock it. I didn’t want to pay. Freddy offered me his. I refused. He insisted. I tried to put him off. In the end, I took it because the mention of the word “Syria” caused him to shiver, because I knew he wanted to look after me, and because my taking it seemed important to him. If I needed to make a call in Syria, I tried to explain to Freddy, I would walk to one of the village shops in which the owner offered pirated international lines at cut rates. I would listen to the other phone conversations underway in the shops, make friends with the patrons, and, in this way, learn about the life of the nation. It wouldn’t occur to the proper, professional reporters to go about things this way. So much the better, I told Freddy. Freddy, a refugee in Turkey, couldn’t understand why I wished to make life more difficult for myself. “You make me afraid,” he told me.

I took the bus from Istanbul to Antakya, the city on the Syrian border in which the international press had established a sort of ersatz headquarters. On the bus, I counted up my cash. I had $200 in my American bank account, available to me through my ATM card. I was managing another $150 in liquid assets, in the form of dollar bills, stray Syrian notes, and Turkish coins. These deposits lived in plastic bags in the interior of my backpack.

So I wasn’t rich, at least not in American money, but neither would I be poor. In Antakya, life was considerably cheaper than it was in Istanbul. Accounting for the falloff in prices, technically speaking, I would probably be rich. At least I might feel that way. As for my budget: Many people in these regions, I knew, lived for six months on $350. A single publishing success would bring me, at the very least, $200. This would allow me to live—and write and hike and make new friends—in Antakya for at least six weeks. The first success will bring on the others, I told myself.

Right away, on my first day in Antakya, I began sending out my pitch letters. What about a story focusing on the music of the Syrian revolution? No one was interested. What about the mysterious-because-incommunicative young men from Libya, France, and Holland one stumbled into in front of the military supply shops in Antakya? “Fascinating,” said one editor, “but not for us.” Austin Tice, a sometime freelancer and full-time law student at Georgetown, had disappeared in Syria in August of that year. A story about Austin Tice? No one was interested. I had an idea about the zany press characters wars attract. What about an update of the 1973 campaign memoir The Boys on the Bus, in which the bus would be the Turkish bars where the next generation of war correspondents was coming of age? No one was interested.

I fell into the habit of waking up early, drinking a glass of orange juice in the restaurant next door to the boardinghouse in which I was staying, then scanning my emails.

Two weeks came and went. One Saturday morning, after I had sent out a blizzard of pitches—after they had yielded nothing at all—I sat by myself in the restaurant with my chin in my hands. I gazed through the restaurant’s plateglass windows. Every fifteen minutes or so, curious, nosing sheep, in troupes of three or four, ambled by. At a plastic table on the sidewalk, a circle of withered, motionless men sat smoking in the sunlight.

During my first hours of meditation, I allowed my thoughts to drift to the hotel, in the fancy Antakya neighborhood, in which the present generation of war correspondents would have been, just then, sipping the foam from their morning cappuccinos. I half-thought of offering myself to one of these properly employed journalists as a translator or a fixer. Perhaps if I hung out at their cappuccino bar for long enough, a crumb, in the form of an assignment, or an editor’s email address, would fall from their table. I would dash off a letter. The editor would bite. Cash would flow. I daydreamed in this way for a little while, then snapped to. Those adventurers were in love with the correspondent flak jacket and the telephoto lens. They knew everything about gadgets and who, in their correspondent bubble, was in love with whom. How could they help me with Syria? It’s beneath me to speak to them at all, I told myself. It would make as much sense, I thought, to ask the sheep on the sidewalk for help. The shepherd, wherever he was, would inform me about the politics of the region. If I were to turn to my fellow café patrons—ancient, trembling men—they would share their wisdom about warfare with me.

Toward ten thirty, I decided that the time had come in my life for Plan B. Maybe I could retire to a youth hostel on the nearby island of Cyprus? If I could get there, I could certainly ride my bike. But then… I was pretty sure I didn’t have the money to get there. A panic seized me. Did I have enough change to pay the gentle, whispering white-bearded man who pressed his oranges in the back of the café? He had told me that he brought in his oranges from the orchards along the Mediterranean coast, to the south of Antakya, in Hatay Province. Those oranges had tasted like fruit from the heavens to me. I would have died of shame if I had not been able to give the orange juice man his money.

I tried to explain to myself how exactly my cash had dwindled away. During the previous ten years, I had angled and schemed and dreamed of turning myself into a Middle East correspondent. There had been Arabic-language academies in Yemen. There had been a period of study in a Koran school in Yemen and a not particularly successful book about what one learns in such a school. During the three years prior to the war, I had been a full-time resident of Damascus. During this period I had fallen in love, as most foreigners do, with the people, the language, and the culture of this place. My career, however, had foundered.

Naturally, I refused to give up. I dug in my heels. I declared my indifference to money. I don’t require rewards from the world of things, I told myself. Now, however, the economics of my career development program were pronouncing a verdict in figures. There wasn’t enough money in this business, it was too obvious and much too late for me to note, or if there was, it wasn’t for me. I would have to find another way.

For the time being, I required only enough to get myself to Cyprus. In order to come up with that cash, I decided that I would write one last essay. Perhaps the new editors of the New Republic would publish it. Perhaps someone else would. That essay would establish, in my own mind, if in no one else’s, that my essays were fun to read, revealing, cool, better than the others. There was no cash value in such essays? Fine. Once I had rung the Syria essay bell, I would cut my losses. I would trim my expectations, pack up, move on.

In order to solemnize this decision, I typed out an email to the person whose opinion mattered more to me than anyone else’s. She had rescued me from a thousand disappointments, not all of which had involved my being broke. Lately, however, a note of plaintiveness had been creeping into her communications.

“For heaven’s sake, sweetheart,” she had taken to saying, into the ether, when we talked over Skype. “You need a Plan B.”

“I know, Mom,” I would reply. “I’m working on it.”

“As they say in Georgia,” she wrote in an email I received the day before my Antakya restaurant reckoning, “ ‘tell me what you know good.’ ” This, I knew, was her way of saying, What in God’s name are you doing in Turkey? Please. Stop being an idiot.

I had been too embarrassed to reply to her question. Now, however, I tapped out a version of the message she wanted to hear:

I’m still trying with the editors. Nothing definite yet. I mean to get one more piece published. I’ll send that around, bargain, negotiate, and maybe this will lead to more steady work somehow. But maybe not. Anyway, I’m planning on writing one more piece. Then, I’m moving on. Okay? Okay?

I had friends in Odessa. There were English-teaching possibilities in Tbilisi, Georgia. Cyprus, however, was nearby. I mentioned these places, wrote a bit about the delicious Turkish oranges, the whispering of the orange juice presser (he spoke a formal old-fashioned variety of Arabic), then pressed “send.” Right away, as if from the phone itself, I heard the sound of my mother sighing in cheerful, exhausted relief.

Having thus committed myself, I turned to my current accounts. My room in the boardinghouse—officially, the Hotel Ercan (in Turkish: the Hotel of the Brave)—was costing me $17 a night. I was spending $10 during the days easily—on coffees in the morning, lunch, cell phone cards for Freddy’s phone, and cans of Efes beer in the evening. A taxi into Syria was going to cost me $20. I would need at least $40 for expenses inside Syria. My mini-audit told me that about $250 of my freelance journalism start-up capital remained. ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Prologue

- Chapter 1: My Plan

- Chapter 2: A Kidnapping

- Chapter 3: The Falcons of the Land of Sham

- Chapter 4: Into the Darkness

- Chapter 5: Their News

- Chapter 6: The Villa Basement

- Chapter 7: Matt’s Escape

- Chapter 8: A Voyage into Darkness

- Chapter 9: The Farmhouse Prison

- Chapter 10: The Caliphate Lives

- Chapter 11: A Voyage with Jebhat al-Nusra

- Chapter 12: My Way Out

- Acknowledgments

- About the Author

- Copyright