- 336 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

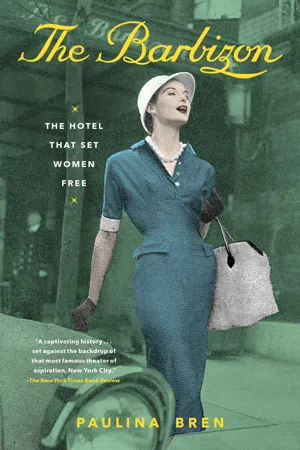

A “captivating portrait” (The Wall Street Journal), both “poignant and intriguing” (The New Republic): from award-winning author Paulina Bren comes the remarkable history of New York’s most famous residential hotel and the women who stayed there, including Grace Kelly, Sylvia Plath, and Joan Didion.

Welcome to New York’s legendary hotel for women, the Barbizon.

Liberated after WWI from home and hearth, women flocked to New York City during the Roaring Twenties. But even as women’s residential hotels became the fashion, the Barbizon stood out; it was designed for young women with artistic aspirations, and included soaring art studios and soundproofed practice rooms. More importantly still, with no men allowed beyond the lobby, the Barbizon signaled respectability, a place where a young woman of a certain class could feel at home.

But as the stock market crashed and the Great Depression set in, the clientele changed, though women’s ambitions did not; the Barbizon Hotel became the go-to destination for any young American woman with a dream to be something more. While Sylvia Plath most famously fictionalized her time there in The Bell Jar, the Barbizon was also where Titanic survivor Molly Brown sang her last aria; where Grace Kelly danced topless in the hallways; where Joan Didion got her first taste of Manhattan; and where both Ali MacGraw and Jaclyn Smith found their calling as actresses. Students of the prestigious Katharine Gibbs Secretarial School had three floors to themselves, Eileen Ford used the hotel as a guest house for her youngest models, and Mademoiselle magazine boarded its summer interns there, including a young designer named Betsey Johnson.

The first ever history of this extraordinary hotel, and of the women who arrived in New York City alone from “elsewhere” with a suitcase and a dream, The Barbizon offers readers a multilayered history of New York City in the 20th century, and of the generations of American women torn between their desire for independence and their looming social expiration date. By providing women a room of their own, the Barbizon was the hotel that set them free.

Welcome to New York’s legendary hotel for women, the Barbizon.

Liberated after WWI from home and hearth, women flocked to New York City during the Roaring Twenties. But even as women’s residential hotels became the fashion, the Barbizon stood out; it was designed for young women with artistic aspirations, and included soaring art studios and soundproofed practice rooms. More importantly still, with no men allowed beyond the lobby, the Barbizon signaled respectability, a place where a young woman of a certain class could feel at home.

But as the stock market crashed and the Great Depression set in, the clientele changed, though women’s ambitions did not; the Barbizon Hotel became the go-to destination for any young American woman with a dream to be something more. While Sylvia Plath most famously fictionalized her time there in The Bell Jar, the Barbizon was also where Titanic survivor Molly Brown sang her last aria; where Grace Kelly danced topless in the hallways; where Joan Didion got her first taste of Manhattan; and where both Ali MacGraw and Jaclyn Smith found their calling as actresses. Students of the prestigious Katharine Gibbs Secretarial School had three floors to themselves, Eileen Ford used the hotel as a guest house for her youngest models, and Mademoiselle magazine boarded its summer interns there, including a young designer named Betsey Johnson.

The first ever history of this extraordinary hotel, and of the women who arrived in New York City alone from “elsewhere” with a suitcase and a dream, The Barbizon offers readers a multilayered history of New York City in the 20th century, and of the generations of American women torn between their desire for independence and their looming social expiration date. By providing women a room of their own, the Barbizon was the hotel that set them free.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Barbizon by Paulina Bren in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Historical Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE BUILDING THE BARBIZON

The Unsinkable Molly Brown vs. the Flappers

The Unsinkable Molly Brown in her prime, already a suffragist and activist, but before she would become the Titanic’s most famous survivor and one of the Barbizon’s early residents.

The New Woman arrived in the closing decade of the nineteenth century. She was a woman intent on being more than just a daughter, wife, and mother. She wanted to explore beyond the four walls of her home; she wanted independence; she wanted liberation from everything that weighed her down. She could be seen pedaling down the street in her bloomers and billowing shirtsleeves on the way to somewhere.

The writer Henry James popularized the term “New Woman” when he used it to describe affluent American female expatriates in Europe living their lives independently of the restrictions back home. But the term gained traction: being a New Woman meant taking control of one’s life.

First there was the Gibson girl, a sort of little sister of the New Woman; upper-middle-class, with flowing hair, voluptuous in all the right places, but cinched in at the waist with a swan-bill corset that had her leaning in, as if she were perpetually in motion, intent on moving forward. Then came World War I, the women’s vote, the Roaring Twenties, and the Gibson girl gave way to a wilder version of herself, the flapper. This little sister dumped the corset, drank, smoked, flirted, and worse. She was all giggles and verve and too much exposed ankle. But the flapper made it clear to anyone willing to listen—or not—that the New Woman had been democratized. To defy traditional expectations was no longer the purview only of those who could afford it. Women, all women, were venturing out into the world now. The war and women’s suffrage had poked holes in earlier arguments for why women needed to stay home. The time had come for the world to adjust. It was in this spirit that the Barbizon Club-Residence for Women was built in 1927.

The Unsinkable Molly Brown, made famous for surviving the Titanic, was among the Barbizon’s first residents. The woman who had mustered up the courage to row-row-row, when the men did not, sat at her small desk in her Barbizon room, pen in hand. It was 1931, and Molly Brown (whose real name was Margaret Tobin Brown) was now a sixty-three-year-old former beauty, overweight, a little rough around the edges, her eccentric and flamboyant fashion sense looking gently comical. But Molly Brown could not care less; she still carried the confidence of a first-generation New Woman, and she knew that no matter what anyone said, she had planted her flag firmly in this new century.

She paused her letter to her friend in Denver and looked out the window of the Barbizon at the bleak February sky. It reminded her of the sky the night the Titanic began to list to the side, far faster than she would have thought possible. That was back in 1912, two years before the First World War, another era altogether now it seemed, when Molly Brown had joined her friends, the famous Astors, on a trip through Egypt and North Africa. Her daughter, a student at the Sorbonne in Paris, met her in Cairo, and together they posed in heavy Edwardian dresses for the must-have souvenir photograph sitting on top of two camels, with the Sphinx and the pyramids looming behind them. Molly returned with her daughter to Paris, but when news arrived that her grandson had fallen ill back home, she quickly booked a cabin on the same ship as the Astors. It was called the Titanic.

It was only the sixth night on board. She had had a nice dinner and was lying comfortably in her first-class cabin, reading, when she heard a crash. She was knocked out of bed, but being a seasoned traveler, she thought little of it even as she noticed the engines had stopped. It was not until James McGough, a Gimbels department store buyer from Philadelphia, ghoulishly appeared at her window, waving his arms and shouting, “Get your life preserver!” that she layered on clothes and headed out. Despite his alarm, up on deck Molly confronted a wide-eyed reluctance to board the lifeboats. She tried to cajole her fellow female first-class passengers onto them until she herself was unceremoniously tossed down into one by the Titanic’s crew. As the lifeboat pulled away, she heard gunshots; it was officers shooting at people on the lower decks who were desperate to jump into the boats reserved for the rich and now launching into the water half-empty.

In the dark, as lifeboat six bobbed in the water, Molly watched in horror. Those around her were crying out for loved ones still on board as water engulfed the Titanic until it was entirely gone, vanished, swallowed up whole. Screams rang out even as everything else had gone silent. It was night, the sea was pitch-black, and the utter incompetence of the two gentlemen on lifeboat six made their hopelessness all the more vivid. Molly Brown, disgusted, took over. She directed the rowing and the will to live, peeling off layers of clothing to give to those who had been less quick-witted. Around dawn, the lifeboat was picked up by the Carpathia, and by the time she and her fellow survivors had pulled into New York Harbor some days later, Molly, ever the activist, had established the Survivor’s Committee, become its chairwoman, and raised $10,000 for its destitute. She wired her Denver attorney: “Water was fine and swimming good. Neptune was exceedingly kind to me and I am now high and dry.” Neptune had been less kind to her friend John Jacob Astor IV; the richest man on board the Titanic was among the dead.

It was almost twenty years later when the Unsinkable Molly Brown took a room at the Barbizon, and the world looked very different despite that same night sky. World War I had been the catalyst for so much change, but for Molly personally, her separation from her husband, J. J. Brown, had been just as significant. They had parted ways: he a womanizer and she an activist. She was a feminist, a child-protection advocate, and a unionizer before it was fashionable to be any of those things. J.J. was a rags-to-riches gold-mining millionaire of Irish descent, and together he and Molly had stepped out of their shared poverty into great wealth, finding a place in Denver’s high society. After their separation, and then J.J.’s death in 1922, which left the family with no will and instead five years of disputation, both Denver’s society circles and Molly’s children turned their backs on her. But this merely stoked her earlier dreams for a life on the stage. Enamored of the legendary French actress Sarah Bernhardt, Molly Brown moved to Paris to study acting, performing in The Merchant of Venice and Antony and Cleopatra. She had both wit and spirit, the kind that could be appreciated there, even in a woman of sixty, and she was soon dubbed the “uncrowned queen of smart Paris.”

However exaggerated the Molly Brown mythology became, her gumption was real. She once wrote of herself: “I am a daughter of adventure. This means I never experience a dull moment and must be prepared for any eventuality. I never know when I may go up in an airplane and come down with a crash, or go motoring and climb a pole, or go off for a walk in the twilight and return all mussed up in an ambulance. That’s my arc, as the astrologers would say. It’s a good one, too, for a person who would rather make a snap-out than a fade-out of life.” Molly Brown was no flapper, far from it, even as her adventurism might have made her one had she been younger. But she was not younger, and she harbored an antipathy toward the flappers, these young women of the Jazz Age who seemed to define themselves by one single hard-won victory that Molly Brown and her generation had worked hard to achieve: sexual liberation. Even so, it was here, at the Barbizon Club-Residence for Women, where Molly Brown decided to stay when she returned to New York from Paris—sharing space with the young women of whom she publicly disapproved but whose core spirit she might well have understood. She chose to stay here because, like them, she wanted to test out different versions of herself, and the Barbizon was the place to do that.

A 1927 street view of the Barbizon, just as its construction was nearing completion.

Molly was delighted with her accommodations. She sent the Barbizon brochure to her Denver friend, marked up and defaced to explain her new life in New York. There is even a radio in every room!, she wrote. Here, circled in thick black ink, was the northwest turret with a bricked-in terrace, looking down onto the corner of Lexington Avenue and Sixty-Third Street. Inside was her suite, one of the best rooms to be had, but even so it was modest, much like the hotel’s regular rooms, which featured a narrow single bed, small desk, a chest of drawers, and a pint-size armchair. One could open and close the door while lying in bed, and you barely had to get up to put something away in the dresser. Humble as it might be, she wrote to her friend that she used her room as her “workshop,” “piled high to the ceiling with things.”

She circled another Gothic window even farther up, on the nineteenth floor, in the Barbizon’s Rapunzel-like tower filled with studios for its budding artists: in this soundproofed room with soaring ceilings Molly sang her arias, practicing for hours. The recital room, she noted, was where the resident artists and artists-to-be gave their concerts. The hotel’s Italianate lobby and mezzanine were where she played cards with friends. The oak-paneled library accommodated her book club meetings. (She most likely participated in meetings of the Pegasus Group, a literary cooperative that gathered at the Barbizon “to encourage the expression of mental achievements by offering authors an opportunity to present their works before the public and to discuss them in an atmosphere of sane, fair and constructive criticism.”) Men—all men other than registered doctors, plumbers, and electricians—were strictly barred from anywhere but the lobby and the eighteenth-floor parlor, to which a gentleman caller could receive a pass if accompanied by his date.

The front entrance of the club-hotel was on Sixty-Third Street, while the ground-floor shops, eight in all, were on the Lexington Avenue side of the corner building, and included a dry cleaner, hairdresser, pharmacy, hosiery store, millinery shop, and a Doubleday bookshop—everything a certain class of woman might need. All the stores had entrances from inside the hotel, off a small corridor, so Molly Brown did not have to venture out onto the street if she was not up to it. The Barbizon had opened only three years earlier, when New York was in the midst of a transformation. A building boom had been in full swing, a purposeful out with the old and in with the new. Public opinion declared that over the years Manhattan had expanded haphazardly, senselessly, illogically, but all that could still be brought to heel. The buildings that belonged to past centuries would be razed to the ground in favor of a new, ambitious, mechanized twentieth century; tenements and low-lying buildings were to give way to well-planned towers that sprang up into the sky in art deco silhouettes.

The architecture of the early twentieth century was as new as the New Woman who had broken free of old constraints. Critics of nineteenth-century New York condemned the “brown mantle spread out” across Manhattan, creating a sea of “monotonous brownstones” in its wake. Today’s prized brownstones, quaint and historical, were then seen as a blight on the city. City planners pointed out that while they could no longer bring back the cheeriness and color blasts of the “old Dutch days of New Amsterdam” with its “red tile roofs, rug-patterned brick facades and gayly painted woodwork,” they could conjure up a new century and its signature look: the skyscraper.

In the midst of this building boom, in 1926 Temple Rodeph Sholom sold its space on Sixty-Third Street and Lexington Avenue in Manhattan for $800,000. One of the oldest Jewish congregations in the United States, soon to be replaced by the premier women-only residential hotel, was moving to the Upper West Side. Temple Sholom had stood at this spot for fifty-five years, following its Jewish immigrant congregation uptown as they moved out of their Lower East Side tenements into new homes in Midtown Manhattan and the Upper East Side. Now again it was following its congregants out of this area that was rapidly building up, especially with the 1918 extension of the Lexington Avenue Line subway from Grand Central at 42nd Street up to 125th Street. The temple ended its half-century-long residency on New York’s Upper East Side with its eldest worshippers onstage to commemorate this moment of change. Mrs. Nathan Bookman, ninety-seven, and Isador Foos, ninety-one, had been members since their confirmations at age thirteen; enthroned onstage, looking down at the congregation of upstanding New Yorkers, their parents and grandparents once Lower East Side German Jewish immigrants, they said goodbye to the nineteenth century. The Barbizon was about to say hello to the twentieth.

Just as Temple Sholom had been built on Sixty-Third and Lexington to accommodate a growing need, so now its planned replacement was responding to an entirely new one. World War I had liberated women, set them on the path to political enfranchisement in 1920 with the passing of the Nineteenth Amendment, and, just as important, made workingwomen visible and more acceptable. A record number of women were now applying to college, and while marriage continued to be the end goal, clerical work combined the glamour of flapper life—with its urban, consumerist excesses (Shopping at Bloomingdale’s! Dinner at Delmonico’s!)—with an acceptable form of training for married life. Clerical work had been a career stepping-stone for young men, but now, as thousands of women headed for the offices inside the sparkling new skyscrapers going up each year across Manhattan, the job of secretary ceased to be a career path with the promise of promotion: it was instead recast as a chance for young women to exercise the skills of “office wife” while also earning a salary and living a brief independent life before marriage. The new secretaries of this new world were to be for their bosses “as much like the vanished wife of his father’s generation as could be arranged,” declared Fortune magazine. They would type their boss’s letters, balance his checkbook, take his daughter to the dentist, and offer him ego-boosting pep talks when necessary.

But the New Woman received something in exchange: the publicly sanctioned right to live independently, to express herself sexually (up to a point), to indulge as a consumer, to experience all the thrills of urban life, and to enter public space on her own terms. And to do that, she needed a place to live. The old-fashioned women’s boarding houses—an earlier option for a single woman living and working in New York—were of a past era, now looked down on with scorn, associated, as the New York Times declared, with “horsehair sofas” and the “recurrent smell of beef stew.” They were also associated with the working class, whereas the new breed of upper- and middle-class workingwomen wanted something better. Neither did they want house rules or patronizing philanthropy (the well-intentioned but demeaning engine behind so many old-fashioned boarding houses for widows, workers, and female outcasts) to be part of their living experience. And the address mattered—a lot.

But even if they had been able to look past the substandard rooms, the itchy horsehair, and the chewy beef, there were nowhere near enough of these boarding houses to accommodate the great numbers of young women pouring into the city. Residential hotels built high into the sky would have to be the answer instead.

Hotel residential living—for families and for bachelors—had been in vogue since the late 1800s. “In town it is no longer quite in taste to build marble palaces, however much money one may have,” wrote one social commentator at the time. “Instead, one lives in a hotel.” Residential hotel accommodations ranged from palatial suites for the perversely wealthy of the Gilded Age to practical rooms for the single and striving. Much fuss and attention were paid to the coziness of these hotel homes. The more modest residential hotels featured custom-made furniture that was intentionally smaller than the standard, making it easier to fit into small spaces and making the hotel rooms appear larger. The twin bed lost its footboard, and the headboard was lowered to create the illusion of space. Furniture corners were rounded for the same reason. At the opulent end of the residential hotel category, rooms were furnished with expensive reproductions of eighte...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Introduction

- Chapter One: Building the Barbizon

- Chapter Two: Surviving the Depression

- Chapter Three: McCarthyism and Its Female Prey

- Chapter Four: The Dollhouse Days

- Chapter Five: Sylvia Plath

- Chapter Six: Joan Didion

- Chapter Seven: The Invisible

- Chapter Eight: “The Problem That Has No Name”

- Chapter Nine: The End of an Era

- Acknowledgments

- About the Author

- Notes

- Image Credits

- Copyright