The Business of Less

The Role of Companies and Households on a Planet in Peril

- 160 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

About this book

The Business of Less rewrites the book on business and the environment.

For the last thirty years, corporate sustainability was synonymous with the pursuit of 'eco-efficiency' and 'win-win' opportunities. The notion of 'eco-efficiency' gives us the illusion that we can achieve environmental sustainability without having to question the pursuit of never-ending economic growth. The 'win-win' paradigm is meant to assure us that companies can be protectors of the environment whilst also being profit maximizers. It is abundantly clear that the state of the natural environment has further degraded instead of improved. This book introduces a new paradigm designed to finally reconcile business and the environment. It is called 'net green', which means that in these times of ecological overshoot businesses need to reduce total environmental impact and not just improve the eco-efficiency of their products. The book also introduces and explains the four pollution prevention principles 'again', 'different', 'less', and 'labor, not materials'. Together, 'net green' and the four pollution prevention principles provide a road map, for businesses and for every household, to a world in which human prosperity and a healthy environment are no longer at odds.

The Business of Less is full of anecdotes and examples. This brings its material to life and makes the book not only very accessible, but also hugely applicable for everyone who is worried about the fate of our planet and is looking for answers.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

1 WHY LESS?

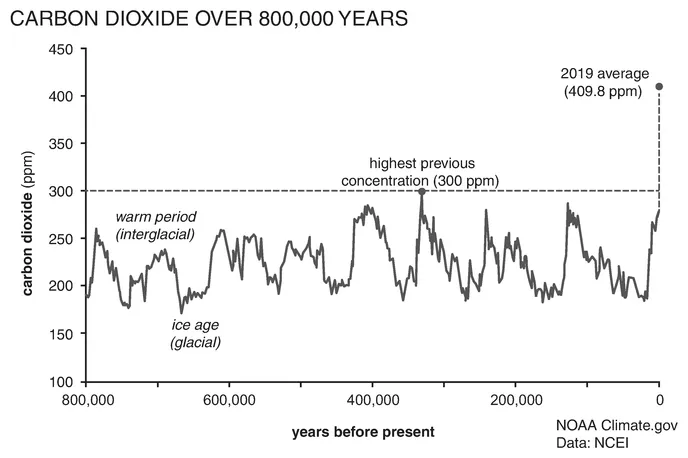

Source: (Image source: NOAA)11

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication Page

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- 1 Why less?

- 2 A brief history of business and the environment

- 3 It’s not easy being green when you’re color blind

- 4 The problem with eco-efficiency

- 5 Why win-win won’t work

- 6 The business of less

- 7 Again

- 8 Different

- 9 Less

- 10 Labor, not materials

- 11 Net green for business

- 12 Net green for households

- Index