![]()

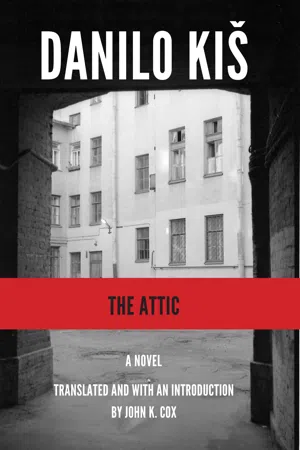

THE ATTIC:

A SATIRICAL POEM

![]()

I listened to invisible trains weeping in the night and to crackly leaves latching onto the hard, frozen earth with their fingernails.

Everywhere packs of ravenous, scraggly dogs came out to meet us. They appeared out of dark doorways and squeezed through narrow openings in the fences. They would accompany us mutely in large packs. But from time to time they would raise their somber, sad eyes to look at us. They had some sort of strange respect for our noiseless steps, for our embraces.

Some heavy blue autumn plums dropped onto the path from a shadowy tree whose branches jutted over a fence. I had never believed that such firm blue plums could exist in autumn. But back then we were so preoccupied with our embraces that we didn’t pay any attention to things like that. And then one night, in a startling flash from the headlights of an old-fashioned car, we noticed that a band of dogs, which had so far followed us silently, was gathering plums, almost reverentially, from the gravelly road and the muddy ditch. All at once it became clear to me why the dogs were so silent and dejected: these wild autumn plums had contracted their vocal cords, as alum would. I heard only the pits, with which they were allaying their hunger, cracking between their teeth. It looked, however, as if they themselves were ashamed of all this; as soon as the car cast the unexpected illumination of its headlights, they hid in the ditch next to the road, though the ones who hadn’t had time to get out of the way remained stock still, as if petrified.

Then the car stopped all of a sudden and out came a man in a sheepskin coat.

“Strange,” he said, but I couldn’t see to whom he addressed these words. I couldn’t tell if there was anyone else in the vehicle because the light wasn’t on.

The man in the sheepskin squatted next to the dog carcasses and contemplated them for a long time, repeating the words “Strange! Strange!”

We flattened ourselves against a cracked old wall in the shadows and held our breath. The only other thing we saw was the man getting back into his car and switching the headlights back on.

It was only when the automobile was already moving down the road that the engine roared to life. That’s when it dawned on me how the man in the sheepskin coat had managed to take the dogs by surprise. The car had been rolling down the road with no lights, in neutral, with the cunning of a wild animal; and the wind was blowing in the opposite direction.

Then we jumped over the ditch and halted at the spot where the car had stood just a moment before. Both of the dogs lay on their right sides, almost symmetrically arranged next to each other. One of them was an old bulldog with a simian snout that the tires had mutilated; the other was a small Pekinese with a medallion around its neck. I stooped down to look at its collar. The following words were stamped into the yellow medallion, no bigger than a fingernail:

—Larron. Crimen amoris.—

I hoped that I’d find a notice in the newspaper, that I’d be able to make a statement and give the medallion back to the dog’s owner, but I was never able to find anyone advertising for his return.

Therefore I took the medallion to a goldsmith one day, after I’d convinced myself that there was no reason not to consider this piece of gold my personal property.

“Larron means swindler,” said the goldsmith without looking up at me.

I was astonished.

“That was my dog’s name,” I said to conceal my embarrassment.

“Strange!” he remarked.

“He liked to steal plums.”

“Plums?” said the goldsmith, looking up at me.

“It cost him his life,” I said.

“Strange,” he said. “And you want me to make you a ring out of this?”

“Yes,” I said.

“Hmmmm,” said he. “Of course, that’s your business.”

Then I said, “You mean you really can’t make a ring out of it.” In those days I didn’t pay any attention to trains. But they tormented me with their screams without my even being conscious of it. Some kind of dark presentiment grew in me, a dread of their howling.

Nonetheless I said one evening, to my own surprise, “I’m afraid of trains.”

“You aren’t afr...