- 128 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

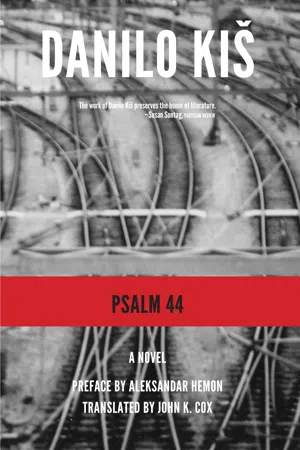

Psalm 44

About this book

Written when he was only twenty-five, before embarking on the masterpieces that would make him an integral figure in twentieth-century letters, Psalm 44 shows Kiš at his most lyrical and unguarded, demonstrating that even in "the place of dragons... covered with the shadow of death, " there can still be poetry. Featuring characters based on actual inmates and warders—including the abominable Dr. Mengele— Psalm 44 is a baring of many of the themes, patterns, and preoccupations Kiš would return to in future, albeit never with the same starkness or immediacy.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

PSALM 44

Chapter 1

For several days already, people had been whispering the news that she was going to attempt an escape before the camp was evacuated. Especially once (and this had happened five or six nights earlier) the thundering of artillery had first become audible in the distance. But then the whispering had died down somewhat—at least it seemed that way to her—since those three other women had been killed on the wire. One of them was Eržika Kon, who’d shared the same barracks.

That’s why all she could do now was listen intently to the cannon and wait for something to happen. She felt every bit as capable of doing something (if only she knew what it was—like, for example those lightbulbs that they knocked down with a stick last night as if they were pears dangling from the arbor in their garden, though it was only thanks to Žana that she was able to do that, thanks to being led by her, because it never would have occurred to her personally to smash lightbulbs and to think of it as anything other than an unnecessary risk, as suicide) as Polja probably felt, Polja who was now lying delirious next to her in the straw. Marija could only wait for Žana to tell her now (in the same way she had until now been saying “not yet,” or less than that, really: only “we’ll see” or “we’ll do something all right”), and then she’d take her child in her arms like a piece of luggage filled with valuables that one had to spirit unseen out the rear entrance right under the noses of the agents who knew that those purloined valuables were about to be removed and probably through that very door. And whenever Žana finally told her it was time, she would take that camouflaged and deliberately inconspicuous suitcase and walk with it through the cordon of agents and police officers, desperately resolved to pass unobserved and proceeding precisely as she’d been told and ordered to act, conscious of her obligation to her instructions, for in this moment (if something unforeseen were to occur), if someone came up to her from behind (let’s say) and tapped on her shoulder to ask her to show her bag, her only defense, the only one she could think up in time, would be to shield the precious bundle, the child, with her own body, perhaps harboring the secret and irrational hope into the bargain that the ground underneath her would open up in that moment and that she would find herself down below in some shadowy courtyard where, with a nod of his head, a deus ex machina would introduce himself to her: that would be Maks. For Maks, invisible and omnipresent, was going to appear and intervene decisively, and the fact that he had already committed himself to the escape—that much had been clear to her from the first instant. Actually from the time (and that was three evenings ago) that Žana had brought hope into the barracks, the hope concealed in her eyes, and she’d said in a whisper that “all is not lost.” And indeed all was not lost. Though Polja was lying in her delirium for a third day on account of malaria and people kept expecting them to come take her away at any moment; it was incomprehensible that they hadn’t taken her away that very first evening when she came back sick and feeble. Perhaps they were showing her (Polja) a little extra consideration on account of her playing cello in the prisoners’ orchestra, right at the entrance to the gas chamber (or so people said) for such a long time; or else—and this was more likely—because of the rapid advance of the Allies and the booming of those heavy guns, ever nearer, forcing the commanders of the camp to postpone any further executions.

That evening Žana returned to the barracks a little late. It was a wet November night, ice cold, and the grim wind carried the worn and ill-tuned sounds of the prisoners’ orchestra playing Beethoven’s Eroica as well as the camp tune “The Girl I Adore.” Polja was still babbling unintelligibly. In Russian. Dying. No one dared light a lamp and Žana made her way, groping, over to her bunk (she oriented herself by Polja’s death rattle). Marija feared that Polja, however, was beyond hearing. Then she freed her child from the straw and rags in which it was sleeping: a little wax doll. Marija didn’t dare get too close to Polja. She feared for her child. And for herself. His mother.

The sound of Žana’s steps reached her ears: this liberated her from thoughts of Polja. And then all at once it dawned on her with great conviction that something must have happened. Whatever it was that had held Žana up this long. A message from Jakob. Or from Maks. (“That Maks” was undoubtedly up to something. Present but invisible.) But Žana said nothing. Marija only heard her light, conspiratorial footsteps. (Suddenly this seemed extremely odd to her: Žana had still not taken off her boots.) Then the rustling of straw, the dull thud of her heavy boots shed, the rusty sound of the tin can of water, and once more the rustling of straw, this time over by Polja, and then: the slight clinking of Polja’s teeth against the can. Marija wanted, in vain, to give some sort of signal, to say something about Polja, not only to express her doubt that she could accompany them on their journey but also to say at last what both she and Žana had known since the first day Polja came back sick, the thing that hovered between them unstated but certain: Polja is going to die. But Žana emancipated Marija from that responsibility and she heard her give a whisper that was eerily like listening to another person give voice to your own newborn thought:

“Elle va mourir à l’aube!” Žana said.

Marija merely sighed in response. She felt her throat constricting. As if she were only now becoming aware—just now when Žana said it—of what she herself had already accepted since the day Polja had come back ill: she was going to die. Now Polja’s discordant rambling seemed more audible than the distant song of the big guns. That’s the reason Marija had wanted to start up a conversation with Žana and have her talk about the cannons, about Jakob, about the escape, ultimately about anything, just so that it would set her free from this nightmare and so that she wouldn’t hear Polja’s death rattle, so that she wouldn’t think about how even after she was dead nothing was going to happen, not now not afterward not in two or in two hundred twenty-two days—just as nothing had happened up to this point; no running away, no Jakob, no Maks, not even any cannons, nothing was going to happen except that same thing which was happening here and now to Polja: she was fading slowly, spluttering, as a candle gutters and goes out.

The rhythmic beaming of the floodlights that entered through a crack in the wall tore again and again, clawlike, at the darkness of the barracks, and Marija caught sight of Žana as she stood between a beam of light and the wall; she stepped into it as if to join the illumination and then disappeared again into the darkness. From there, out of that momentarily illuminated darkness, she could hear her voice, her whisper, which like a focused beam of light cut the silence:

“Jan . . . How is Jan?”

“He went to sleep,” Marija answered. “He’s sleeping.” But that wasn’t what she’d thought she was going to hear from Žana, she’d expected something different, something completely different than the question Jan . . . How is Jan? and she was even certain that Žana had something else to say and it even seemed to her that when Žana greeted her in a whisper, and even before that point, when Žana had still only been thinking of speaking (and it had seemed to the listener that she knew exactly the instant when Žana would start to talk and shatter the silence), that she was going to say something else, for she had to say something completely different, something that (nevertheless) would not be unrelated to this issue; it even struck her now, suddenly (more from the pounding of her pulse than from an actual understanding), that the question Jan . . . How is Jan? didn’t differ in essence from the question that Žana really needed to ask. Thus—wondering whet...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Contents

- Other Works by Danilo Kiš in English Translation

- Preface

- Psalm 44

- Translator’s Afterword

- Translator’s Notes

- Copyright

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Psalm 44 by Danilo Kis, John K. Cox in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Littérature & Littérature générale. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.